David Means on the World As

Endless Inspiration

"Art arrives out of a tension between the private and the public..."

If you go into a painter’s studio you’ll often find things pinned to the walls above a workbench—photographs, postcards, and, on the bench, bits of canvas, driftwood, old tools. In the artist studio you’ll often hear music blaring. Above my own desk—a kind of workbench—I have, among photos and posters and quotes, a snippet of a poem by Adrienne Rich called “Cartographies of Silence,” something I read years ago, as an undergraduate, and still love:

A conversation begins

with a lie. And each

speaker of the so-called common language feels

the ice-floe split, the drift apart. . .

I don’t know exactly why I found, and still find her poem so useful, but I do. Perhaps it’s the extreme way she digs into the limitation of language and love, which moves to the image of nature, the ice-floe. The word inspiration has become threadbare, and somewhat a catch-all. To be honest, I’m not really sure how to talk about it. I try to think of whatever it is in other ways: seeds, fuel pellets, the Muse. To me, whatever it is, inspiration has a physical quality—a piece of visual art, a photograph, some words, a memory—and a kind of physics, form and structure, and some unnamable, enigmatic force. You need to be open, I think, to the possibility of finding something that will spark the imagination in everything you see, read, or hear. This aspect of the artist life, like anything else, takes practice.

I believe strongly that—as a fiction writer at least—one should protect and hold close certain seeds; those seeds might include a few of the acute, painful memories that fuel the desire to create. This might just be my own way of working, but privacy, and a sense that certain things deserve to be protected, can also be inspiring in a world that demands confession, openness.

Art arrives out of a tension between the private and the public, between the creator and the creation. Storytelling blooms out of a need, a sharp desire, to catch narrative, and that need—fragile, delicately wedded to the inner conversation of each writer—deserves to be tenderly cared for and respected. Whatever inspiration is, it will always—as I see it—feel intimately, and often weirdly, wedded to the self. When exposed, it will often seem suspect, or strange, because it is often impossible for the reader to locate the direct connection to the creative work.

Here are a few recent things that have touched me—in no particular order.

I. In 1955 the photographer W. Eugene Smith went to Pittsburgh on a “routine, freelance” assignment for LIFE magazine in 1955 and ended up spending four years on the project, working obsessively, and making around 17,000 photographs of the city.

You go into writing pretending you’re under contract to do one thing, and you end up doing another thing. An obsession with a single place on the map.

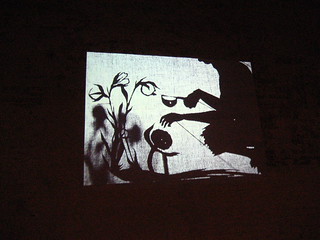

II. Kara Walker’s silhouettes.

I remember walking into a museum in New York and seeing Walker’s work for the first time and being completely overwhelmed by their narrative power. Precise shapes, the way shadow overpowers the desire and need for detail. Too much detail can obliterate the power of narrative.

III. Francis Bacon’s studio, and his work.

I remember exiting an exhibit of his paintings at the Met, moving from his intensely distorted figures, and all of that pain, into the gilded halls, the old masters lined up, and feeling a disequilibrium that was inspiring. That’s what a collection of stories can do.

IV. Brancusi’s studio at the Centre Pompidou.

I love his burnished, perfected sculptures. But along with his forms, I’m inspired by the obsessive amount of time he spent on his wooden bases for his sculptures, going from one to the next and back again in a determination to get them exactly right.

V. JG Ballard’s daily visits to the Heathrow airport terminal building.

I respect the desire to go again and again to some banal, everyday place. And Ballard found delight and inspiration living in Shepperton, a suburb of London. Sometimes you’ve got to admit that it’s better to live on the outside, to be inside something that seems brutally bland on a daily basis, to locate the seeds of story in everyday life.

VI. Ed Rusha’s photographs: Thirty-four Parking Lots. And Various Small Fires!

His obsessive focus on various forms of similar structures. I can admit now, years later, that the title of Assorted Fire Events was drawn from Rusha.

VII. William Eggleston’s white gloves, and his one-shot-per-subject rule.

I’m intrigued by rules an artist sets for no good reason except that they work. Finding these rules is a part of the creative process, and the rules might shift as you grow and change.

VIII. Walker Evan’s photographs of tools for FORTUNE.

He turned an assignment for a business magazine into art.

VIV. James Agee’s Guggenheim application.

The exuberant openness of his creative spirit. What happened to this kind of wildness? Is it still around? I think it is.

X. William Carlos Williams jotting a poem on his prescription pad, gazing out at the meadowlands, waving from his car as he passed, the iceman, the milkman. Williams took what he needed from everyday life. A first-generation American, he located the language, the language.

XI. Thelonious Monk refusing to speak for days, months.

I understand the desire to turn away, to refuse to speak, to let the work do all the speaking.

XII. Miles Davis turning his back on the audience and facing his band.

Turning away from the audience and performing towards those who create the work, or those who will truly appreciate and understand the work.

XIII. Anne Carson’s The Beauty of the Husband

The perplexity and duplicity of relationship. . .turning to poetry, essays, and short fiction when necessary. The narrator admits, on page five, perhaps with a bit of irony, that she stayed with her husband for so many years because he was beautiful. I’m find inspiration in Carson’s willingness to move from form to form, to find the right container for each vision.

XIV. Danny Brown in a studio in Detroit, laying down rhymes.

The Michigan streets in the snow. Art blooming in a Midwestern industrial landscape. You must channel the urgency to create, to make art.

XV. Cindy Sherman—her photographs, and the fact that when she’s working, she works alone, without an assistant.

Making herself up, getting into costume, adjusting the lens, creating her characters alone in her studio. You feel that isolation—no help from an assistant—in her photos.

XVI. Louis Gates’ The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African American Literary Criticism.

A book that searches and finds the folkloric sources of language, tracing, as much as possible, the original patterns. Find seeds in searching for original sources, in the physicality of trying to get close to primal structures.

*

Unlike the visual artist, the writer is, perhaps, more dependent on finding inspiration in memory fragments, bits of the past, images caught in passing. Staring is a big part of being a writer—and these images usually enter the fiction unexpectedly, as a surprise. It’s important—at least to me—that there is no intention at hand when writing, that these things reappear as part of the magic of drawing up from well of the imagination. But at the same time, these fragments—the wide Cleveland streets on a dull summer afternoon, the astonishing stink of the men’s room at Grand Central, the ruddy face of a conductor on the train, the nubs of gum pressed into a kind of macadam on the station platform—are collected, pinned above the mental workbench. As a writer you must practice looking and, while you look, attempt to find words that can describe images. Even the smallest memories can become a form of inspiration.

At the Michigan State Mental hospital years ago, visiting my sister who was a patient there in the 1980s, I saw clipboards hanging on hooks in the wall of the nurse’s station. The door was open and a summer breeze came in and rattled them softly. It took twenty or more years, but that image appeared in my fiction. That’s another inspiration: images that I collect with intent, and sometimes without intent, that I hold onto for future use.

I’m inspired by the isolate shore of Lake Superior, rocky and cold, and the shore of the Hudson at low tide; I’m inspired by the ramshackle remains of an old brick factory (and least I think it’s a brick factory) along a railroad right-of-way near Poughkeepsie; a storefront in Brooklyn with old signage; a field sloping down from a country manor outside Galway, threaded with ancient stone walls, to a creek–inside landscape lies story. I like to look and then stare and then stare some more, searching for sparks of narrative inside landscapes.

Once, on a rambling road trip from Arizona to New Mexico, crossing the Zuni reservation, I stopped with my friend to look at El Morro, a stone outcropping in the flat desert plane with petroglyph, Civil War-era graffiti, names and dates. A few years before that, I saw the face of a young woman on Sunset Blvd in LA. On the way to El Morro, crossing the mountains between AZ and NM, we were stopped by a woman holding a stop sign in the early hours of morning, warning of a blocked road; my sister and her friends; a ranger station. I looked and looked and looked for twenty minutes while my friend waited for me; I took in El Morro and saved it for later, not knowing that LA, and a horseback ride I took with my daughter when she was a young girl in the Hollywood hills while my wife was attending a teacher’s union convention, and that woman with the stop sign would arrive with the muse and enter a story years later.

![]()

David Means’ Instructions For A Funeral: Stories is out now via Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Previous Article

The Stories We Tell Our SonsAbout Becoming Men

Next Article

Leila Slimani Doesn't Care IfYou're Uncomfortable