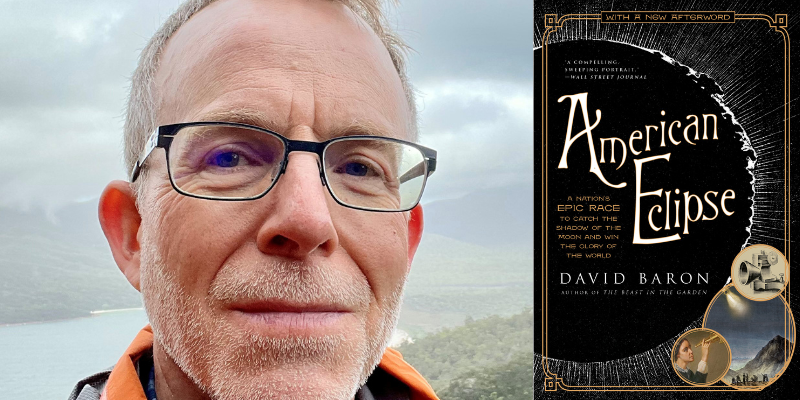

David Baron on What Literature Tells Us About the 2024 Eclipse

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

In anticipation of the total solar eclipse forecast for April 8, author and journalist David Baron joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss his award-winning book, American Eclipse, which chronicles the remarkable solar eclipse of 1878. Baron, a self-proclaimed umbraphile, or eclipse chaser, explains why he chose to write about the Wild West-era event, which darkened skies from Montana to Texas. He also talks about what has driven him to see eight total solar eclipses across the globe. As the upcoming eclipse is forecast to affect a sizable swath of the U.S.—the last time this will happen until 2045—he reflects on why these rare occurrences captivate humanity and discusses how their lore has influenced famous writers, including Mark Twain and Emily Dickinson. He reads from American Eclipse.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf and Amanda Trout.

*

From the episode:

V.V. Ganeshananthan: Our obsession with eclipses also goes deep into the past and eclipses have been appearing in our art and literature for centuries. Milton, Wordsworth, Thomas Hardy, all featured eclipses in their poetry. And there’s a Dickinson poem with an eclipse, which I will read a little snippet of.

It sounded as if the Streets were running

And then — the Streets stood still —

Eclipse — was all we could see at the Window

And Awe — was all we could feel.

By and by — the boldest stole out of his Covert

To see if Time was there —

Nature was in an Opal Apron,

Mixing fresher Air.

What role do eclipses tend to play in literature? Why are they not so fascinating just to the general population, but also fascinating and specifically useful to writers?

David Baron: Well, I think it’s changed over the centuries. So, before astronomers knew how to predict eclipses, and before they really knew what was happening, of course, they were seen as bad omens. It was nature out of order. It was supposed to be a sign from the heavens that we needed to change our ways. And in fact, Shakespeare refers to eclipses in several of his plays. In King Lear, he has Gloster say, “These late eclipses in the sun and moon portend no good to us.” And that was generally the idea in ancient times that, again, a total eclipse was a sign of something wrong.

In more recent times, and by recent I mean in recent centuries, because it’s been several centuries since astronomers were pretty good at predicting where and when eclipses would happen, they’ve become more just an opportunity to appreciate, as Emily Dickinson did, the awe of standing in front of natural forces so enormous and incomprehensible that they make us feel humbled.

One of my favorite essays about a total eclipse was by the 19th century novelist James Fenimore Cooper. In 1806, he witnessed a total solar eclipse in his hometown of Cooperstown, New York, when he was just 17 years old. And much later in life, he wrote an essay that ended up being published posthumously, where he talked about – again, he was 17 years old, he then went on to lead a very productive and interesting life… But, he looked back on that eclipse as one of the most meaningful experiences in his life.

I have a brief quote in my book from that essay, where he writes — this is him as an older man, looking back on what happened when he was 17 — “I shall only say that I have passed a varied and eventful life, that it has been my fortune to see Earth, heavens, ocean, and man in most of their aspects, but never have I beheld any spectacle, which so plainly manifested the majesty of the Creator, or so forcibly taught the lesson of humility to man as a total eclipse of the sun.” And again, I think in more modern times, that’s what you see, it’s an appreciation of being alive and whether you believe these are supernatural forces or natural forces, we are at the mercy of a universe that is so much larger than we can comprehend.

Whitney Terrell: That’s true, and I was thinking about the Dickinson poem, that was an 1891 poem called, “It sounded as if the Streets were running.” And so that must have been about the same eclipse that you write about in your book, probably, right?

DB: I don’t know what she was writing about because mine is 1878, and it was not total in Massachusetts.

WT: She was born in 1830. So I was trying to figure out — do you know if there was another one in between 1830 and 1878?

DB: There were several. There was one that was total in 1869, but that was not total in Massachusetts. There was no total eclipse in Massachusetts in those years, I am quite sure. But she might be writing of a partial eclipse, or she might simply be writing from her own imagination, as far as we know.

WT: So the interesting thing about eclipses as a literary device, right, is that they’re… Well, first of all, I want to mention there’s also a religious aspect to this, right? They can be about all of nature, but your book begins with a guy who runs in and kills his family, because he wants to avoid end times. And that is, in 1878, a fairly contemporary interpretation. I still think there’s plenty of people in this country that believe that God created the universe in X number of days and may take this as a religious portent as well.

But in literature, it’s kind of difficult because characters don’t cause eclipses. They’re a deus ex machina in a way. They’re the hand of God literally, or as some people imagine the hand of God, and yet they do work as a narrative way of defining a before and after. I wonder if you could just talk about the way that they are sometimes used in literature.

DB: Well, I think they are sort of a deus ex machina, because it is something that again, unless you know how to predict it, it just comes out of nowhere and seems inexplicable, and can be terrifying, and can change lives and history. So a true story, and this is related by the ancient Greek historian Herodotus.

In the sixth century BC, in Asia Minor, these two warring powers, the Medes and the Lydians, they’d been fighting for six years. And all of a sudden, in the middle of day, the sun disappears. And they considered it a sign from heaven that they needed to lay down their arms, and they made peace. So this actually happened in real life. And so yeah, it’s a wonderful technique in literature as well if you want to suddenly have people change their ways and perhaps realize the folly of what they’re doing.

VVG: I wish I could aim the eclipse at several people, just like that. Anyway, so your book American Eclipse covers 1878’s eclipse by weaving together the stories of many Americans who witnessed it. And the book is built off both minor tales of people who witnessed the eclipse, as well as several key individuals who specifically sought out the eclipse traveling, as you were just saying that many people are doing for the upcoming one. So what made you choose — why 1878’s eclipse when there are, as you were sharing with us, so many choices?

DB: I guess I’ll go back to how the book all came about, which is both out of my own personal passion for eclipses (when I saw my first one in Aruba in 1998), and my first total eclipse, and also out of a marketing opportunity. So it was in 1998, I was just absolutely awed when I saw my first total eclipse, and I was a science writer working in public radio, but thought I really wanted to write a book that somehow brought to life, to the general public, the excitement of a total eclipse. I figured I would have the book come out first in 2017, 19 years later, because that’s when the next total solar eclipse would cross the United States, and then there’d be another in 2024.

I was looking for a good eclipse tale to tell, a good human story that centered on an eclipse. And it became pretty clear early on that the best eclipse stories are not from today, but they’re from the 19th century because in the 19th century, particularly the latter half, total eclipses were keenly important for science, for astronomy.

Astronomers were just starting to unravel the mysteries of the sun. What is this great ball of fire in the sky? What is it made of? What fuels it? And there were certain studies that they could do only during a total solar eclipse, which as I said, happens about once every 18 months somewhere on the planet, usually someplace very hard to get to, and only lasts three or four minutes. But it was so important. They’d put together these elaborate expeditions, head off to Africa or Asia or the Arctic, set up their telescopes and spectroscopes in the path of the moon shadow, hope that clouds didn’t show up, and then frantically conduct their observations in these three or four minutes.

So I wanted to write a book about one of these eclipses, and I just started going through them. There was one in 1868 that went over Thailand, 1870 over the Mediterranean, 1871 over India. And then it came to 1878, and it just had everything that a writer could want.

Here it was, I mean, the setting: across the Wild West. The eclipse of 1878 went right down the spine of the Rockies from Montana territory to Texas. It was the Gilded Age in the east. It was so important to science at that time, you had all of these eastern scientists and European scientists rushing out to the Wild West. Among them was Thomas Edison. A young Thomas Edison, just before he invented the lightbulb, went to Wyoming with the gunslingers and the saloons to witness this total eclipse.

And also, this was a really important time in the history of science in America. We were a young country, we had just turned one hundred a couple of years earlier, we were becoming an economic power. But the Europeans didn’t take us seriously when it came to intellect. I mean, Europe was where the great art and literature and music and science came from. And here was America’s chance to show that it could be a scientific nation, it could compete with Europe in this intellectual realm. And so it became a really big deal for the country. So Edison, I knew early on, was going to be one of my characters.

There were so many interesting people, but I ended up focusing on two others as well, who I’m sure we’ll talk about. But my favorite of the three characters was actually the most famous female scientist in America in the 19th century. Her name was Maria Mitchell, she taught at Vassar College, she taught astronomy. In 1878, when all these men were heading out to the Wild West with their telescopes to observe the eclipse, and the government was asking them to come along, and she was excluded, she took it upon herself to put together an all-female expedition to Denver, Colorado, for the eclipse of 1878. So it was just a great setting, great time, and wonderful characters. And it just screamed a book.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Madelyn Valento. Photo of David Baron © David Baron.

*

American Eclipse: A Nation’s Epic Race to Catch the Shadow of the Moon and Win the Glory of the World • Beast In The Garden: The True Story Of A Predator’s Deadly Return To Suburban America • TED Talk: “You owe it to yourself to experience a solar eclipse”

Others:

“It Sounded as if the Streets Were Running” by Emily Dickinson • King Lear by William Shakespeare • The Eclipse by James Fenimore Cooper • “Battle of the Eclipse in the Lydian and Median War of Ancient Greece” | GreekBoston.com • A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court by Mark Twain • Teaching a Stone to Talk: Expeditions and Encounters by Annie Dillard • Superman IV: The Quest for Peace • Log Your Eclipse | Eclipse-Chasers.com • “Eclipse Literature” by Lara Dodds | Northwestern University • The Eclipse, or the Courtship of the Sun and the Moon