Dara Barrois/Dixon on the Lived Poetry of the Late James Tate

Peter Mishler Talks to One of the Editors of Hell, I Love Everybody: The Essential James Tate

For this installment in a series of interviews with contemporary poets, Peter Mishler corresponded with Dara Barrois/Dixon, co-editor of Hell, I Love Everybody: The Essential James Tate (Ecco). Barrois/Dixon (née Wier) is the author of several collections of poetry, including five titles from Wave Books. Dara Barrois/Dixon’s most recent book is Tolstoy Killed Anna Karenina from Wave Books.

Barrois/Dixon was married to James Tate for over twenty-five years. Tate, who died in 2015, is widely considered an indispensable and inimitable American poet. He was the recipient of the Pulitzer Prize, a National Book Award, and the Yale Younger Poets prize.

*

Peter Mishler: What was the most startling observation you made while going through Jim’s entire oeuvre? Was there a gesture, theme or even and image that you were surprised to notice consistently for the first time?

Dara Barrois/Dixon: Nothing startling, plenty arresting, plenty satisfying, renewing attachments to poems, finding new favorites, remaining impressed most of all with Jim’s dedication to imagination. Good to see and follow the poems changing over the years, while they never stop paying close attention to who people are and how we live. John Ashbery once called Jim’s poems “dazzling,” and that feels about right to me.

Oh, wait, there is one thing—we’ve been putting together an audiobook, and it’s been stunning to hear how beautifully Jim reads his poems from the get-go, no posing, no drama, no hesitation, you believe he means every word he says and that he’s saying them right to you.

I listened to Terrance Hayes’ foreword and then the rest of the book, read by Michael Earl Craig who reads for the audiobook when we couldn’t locate some of the poems read by Jim. I could not stop myself from tearing up because of how right Earl’s reading is.

PM: What about the process of selecting and editing and working on this book felt the most authentic to Jim, the person you know and love? Was there something in particular that you felt you needed to honor?

DB/D: Impossible questions! No temptation to second guess him—as in What Would James Tate Do? Just not possible. First off, his being impossible to predict or pin down is one of the things that make his poems and him irresistible.

We’ve been putting together an audiobook, and it’s been stunning to hear how beautifully Jim reads his poems from the get-go, no posing, no drama, no hesitation, you believe he means every word he says and that he’s saying them right to you.PM: Were there any special or unusual techniques, practices, or procedures that helped you in the process of selecting poems, perhaps something that happened that felt most like the unexpected, mysterious, preternatural, unknowingness that accompanies poetry in general?

DB/D: We, co-editors, Emily Pettit and Kate Lindroos, read Jim’s books one book at a time chronologically, met biweekly over zoom, read poems to one another, aimed to make a small book, made up of quintessential Tate poems, ones we had an inkling others liked and loved, ones you might want to show to someone else. Sometimes others joined us, Rachel B. Glaser, Lesle Lewis, James Haug—it wasn’t easy. It took several rounds and different approaches.

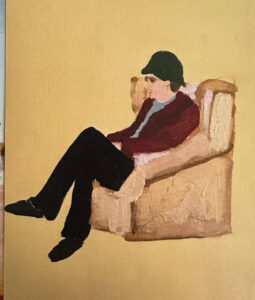

Painting of James Tate by Emily Pettit

Painting of James Tate by Emily Pettit

We whittled an initial selection of over two hundred poems down to around a hundred, and then to what’s now the book’s fifty-two. The book’s not intended to be definitive or complete. I’d be being what’s called aspirational if I make up a story about our procedures being mysterious and preternatural—his poems may be those things. We focused on being as careful as we could be to include a range and present it as unobtrusively as we could.

PM: Is there a poem in particular that you brought to these zoom sessions that you felt should surely be included? Which poem and why?

DB/D: I don’t think so, not just one. We read and talked about a few dozen poems every time we met. Like I’ve said, I can’t speak for Emily or Kate. One of the reasons I didn’t want to edit the book alone is that I wanted to have poems called to my attention that maybe I’d have neglected. Emily and Kate brought their own experience and open-mindedness to our work.

I love how we didn’t see poems in the same ways. I think that’s one of the strengths of the book. It’s honestly eclectic.

PM: Given your long relationship with Jim, is there a particular poem in this collection that you feel in some way speaks directly to you?

DB/D: This goes beyond difficult! I think every poem in this book and so many others we had to leave out speak directly to me—that’s really all I hope for from any poem by anyone. Directly to me means the poem gets right in there in a way I want to surrender my brain to its way of thinking, gladly and likely for something good—I think reading anything worth reading will lead our thoughts down new paths by new means—I think it’s what we mean when we say something’s worth reading.

All that said, “The Formal Invitation” and “Uneasy about the Sounds of Some Night-Wandering Animal” and “Distance from Loved Ones,” “Toads Talking by a River,” and “Of Whom Am I Afraid,” and “Suffering Bastards,” “Stray Animals,” “A Largely Questioning Article Offering Few Answers,” “Dream On,” and “I Sat at My Desk….” I could single out as having blown me over the first time I read them, and this has never changed.

And believe me, this list could have gone on. However! For the sake of answering your question asking for “a particular poem,” I’m going to say, “Uneasy about the Sounds of Some Night-Wandering Animal.”

For part of a winter and a spring I lived in Missoula, Montana being a visiting poet at the University there. It was in the mid 1990s when faxing was still one fast way to send printed documents around. The fax I used stood in a corner of a little coffee shop not far from the rented house I lived in. It was not unusual for me to have talked to Jim in the morning and again at night.

This morning, he said he’d be faxing me a new poem later in the day. I’m sure as I read the poem as it came rolling out of the fax machine my body sent out electrified bolts of raptured consciousness. To read for the first time “How the Pope Is Chosen,” as line by line it exits a fax machine constitutes an ultra-divine poetry encounter.

James Tate

James Tate

PM: To what extent did engaging with JT’s body of work so deeply have an effect on your writing or thinking or way of seeing, if at all?

DB/D: Putting together this book was certainly a different way of engaging with Jim’s body of work than I’d previously experienced. I feel lucky that I’ve had a close engagement with his poems ever since Jim and I became partners.

I think I’m more interested in hearing what my fellow editors might have to say about this question. Jim and I wrote together in the same house across the hall from one another for over twenty-five years. At the end of the day, he’d read mine to me, and I’d read his to him.

PM: What was that like to hear someone else reading your poem back to you at the end of the day after having written it?

DB/D: Because he’s someone I trusted and understood would not want me to fool myself by being boring or dull, I couldn’t wait to hear how it went when Jim read to me—I could tell when it clicked in and when it didn’t. This is about all I ever needed to know.

PM: I’m thinking about you reading his poems back to him. You were talking about him reading your poems and listening to hear if the poem “clicked.” Could you say what you think Jim was listening for when you read his work to him?

DB/D: I understand “clicked” to mean something related to understood, believing your thoughts to be understood—shifts and shades of tones, what’s tragic, what’s not, I believe seeing and hearing someone take in your words for the first time brings you close to the uncanny truth that we can sometimes understand one another, that words and shades of meaning and those sometimes hard to get to deep inside feelings we live by can be mutual, or at least come close. It’s also understood that understanding isn’t static, or cut and dry.

I’d say this is one reason why people like to read to other people and to listen to others read, in public, without the benefit of second thoughts, at least at first. I like the somewhat frightening, bracing aspect of this. It’s terrifying and it’s necessary, at least it seems so.

My first consciously understood love for poetry, and prose too, has been how it lets me imagine sensations of being as close as I’ll ever be to feeling I’m following along with another person’s thoughts, even when there’s a fantastic illusion involved. That’s real. I like to believe this illusion really can help us feel not so alone. Proust says something along the lines of, when I look up from a book, nothing’s unakin.

PM: I mentioned this to you previously, but I was struck by how many of the poems in this book are “about” poetry in some way. This is something I feel like I’ve always known about his work, but seeing so many of them gathered in one place refreshed this aspect. I wonder what your thoughts are about this impulse in his work?

DB/D: Interesting. I’ve looked at the book with this in mind, and you’re right, there are a certain number of poems that can be taken to be “about” poetry: “Read the Great Poets,” “Dear Reader,” “Teaching the Ape to Write Poems,” “Toads Talking by a River,” and “The Book Club,” “Of Whom Am I Afraid,” “Suffering Bastards,” “Stray Animals,” “Dream On,” “I Sat at My Desk….” Well, that’s a good many.

All these do come at it from a lot of different angles. Maybe “Dream On” is my top favorite of these:

Radiant childhood sweetheart,

secret code of everlasting joy and sorrow,

fanciful pen strokes beneath the eyelids:

all day, all night meditation, knot of hope, kernel of desire

pure ordinariness of life,

seeing, through poetry, a benediction

or a bed to lie down on, to connect, reveal,

explore, to imbue meaning on the day’s extravagant labor.

He lived for poetry so it seems natural poetry would find its way into a lot of his poems just as love and life and death, beauty and truth and those blue antelope, babies and donkeys and dogs do.

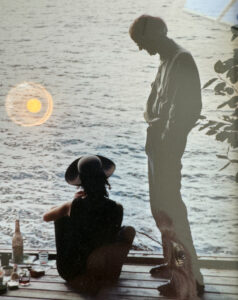

Photo of Dara and Jim by Mary Ruefle

Photo of Dara and Jim by Mary Ruefle

PM: On what, in art or poetry, did you and Jim tend to disagree?

DB/D: This feels like a trick question! Like those ones when someone asks, and what can you say are your weaknesses….After all, I’m pretty sure we liked one another because we recognized we agreed about a lot of things, maybe the most important things. This relates to the above, it’s also about being understood and understanding. I’m sure there’s a world of things we’d disagree about, if say we were given the same quiz to take.

He lived for poetry so it seems natural poetry would find its way into a lot of his poems just as love and life and death, beauty and truth and those blue antelope, babies and donkeys and dogs do.One of the hardest things to learn to live with when someone can’t be with you all the time is that the long-standing, on-going conversation that happens when we say we know one another has been interrupted. You can imagine what someone might say or do or want you to do, you can hope. You can imagine what superficially might seem at odds, but poetry is nothing if not the birthplace, safe house, habitat—of conundrum, enigma, paradox and mystery.

We disagreed about extremely loud chase/crash movies. I didn’t like them. One time he worried I was reading too much Blake.

Dara Barrois/Dixon

Dara Barrois/Dixon

PM: What did it feel like to engage exclusively with another human being through pages of their work alone?

DB/D: It feels as if you’re being given an extra life to live.

______________________________

Hell, I Love Everybody is available via Ecco.