Daniel M. Lavery on the Reckless Optimism of Advice Columnists

“The letter-writer is free to cheerfully ignore the advice columnist.”

“Mother’s gone too far. She’s put cardboard over her half of the television. We rented Man Without a Face—I didn’t even know he had a problem! What should I do?”

–Principal Skinner, “In Marge We Trust,” The Simpsons, season eight

*Article continues after advertisement

Any discussion of the American advice-giving industry is likely to include a reference to Miss Lonelyhearts, Nathanael West’s bleak 1933 novella about an unnamed journalist who is press-ganged by his hostile boss into writing an agony-aunt advice column before suffering through a series of increasingly squalid sexual encounters, bar fights, and alienating religious revelations. The protagonist periodically stumbles off to visit his ex-fiancée Betty in the hopes of borrowing some of her straight-laced assuredness, believing that “her sureness was based on the power to limit experience arbitrarily,” but that “his confusion was significant, while her order was not.”

There’s a cheerful, reckless sort of optimism to the arbitrarily-limited format of the advice column—to say, “Two or three paragraphs describing your life thus far ought to supply me with sufficient information to make a judgment on your behalf; I’ll send a paragraph or two in reply explaining what to do next. Anywhere from a few thousand to a few hundred thousand strangers will be reading this correspondence, of course, and quite a few of them will want to weigh in afterwards in the comments section, possibly about your problem and possibly about to what degree they believe you to be a faithful representative of your own situation, and possibly about problems they themselves are facing that they think are more interesting than your problem was in the first place. Then you’ll either take my advice or ignore it—I’ll never know which—and odds are we’ll never interact with one another again.”

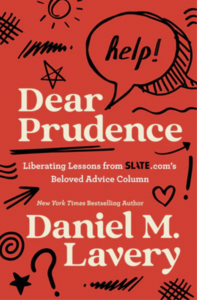

This type of exchange has proved to be a widely beloved and durable method of American social interaction; almost every newspaper in the country still carries the Dear Abby or Ann Landers columns (now in their seventh and eighth decades, respectively), and sometimes both. There’s Ask E. Jean, Dear Sugar, ¡Hola Papi!, Carolyn Hax, Ask Polly, and Dear Margo, among others. Between 2015 and 2021, I served as Slate’s fourth Dear Prudence, where I answered roughly forty questions a week, 52 weeks a year.

The letter-writer is free to cheerfully ignore the advice columnist, or do the opposite of whatever I’ve suggested.The majority of my life, of course, has not been spent as an advice columnist. I dedicated a little less than five years to the job; before I took it on, no strangers ever asked me for advice, and once I left the job, I promptly resumed that formerly untroubled position. During those five years, any number of strangers would send me a few paragraphs, describing their immediate problems as they understood them, alongside a précis of however many characters they believed to be relevant, again as the letter-writer understood them.

I would then do my best to decide whether I believed the letter-writer to be a faithful representative of their own condition, what I thought they ought to do next, what I thought they thought they ought to do next, what might prove a meaningful compromise between those two perspectives, and then if time permitted, come up with a pithy signoff.

An unexpected benefit of this assembly-line approach to offering advice is that one’s own judgment becomes cheap—it’s difficult to remain too impressed with one’s own good opinion when that opinion must be reproduced consistently and to order, like diner pancakes, throughout the work-week.

This is also a useful safeguard against preciousness, the enemy of every writer working under deadline; the first pancake, every home cook knows, is always a dud, destined either for the dog’s dish or the trash can, and it’s the second pancake that’s really the first. Because the syndicated advice-column exchange is both public and anonymous at the same time, it allows for maximal frankness, directness, and clarity. There is no small talk or soft-pedaling required in order to save face or preserve an ongoing relationship.

The letter-writer is free to cheerfully ignore the advice columnist, or do the opposite of whatever I’ve suggested, or write to another advice columnist they think will give them a better answer, as they see fit; I have no way of monitoring or controlling their behavior at any point during or after our time-delayed conversation. “Here’s an idea” and “This might help” are the advice-giver’s by-words.

Readers might recall Marge Simpson’s tenure as the Listen Lady while she fills in for a disillusioned Reverend Lovejoy solving parishioner’s personal problems at the First Church of Springfield in the 1997 episode, “In Marge We Trust.” His lay replacement is an immediate success, much to his dismay, and the viewer realizes that if this Listen Lady is all she’s cracked up to be, she’ll have to find a way to neutralize her own success, rendering herself unnecessary in order to solve the Reverend’s problem.

Yet while Marge knows inevitably that she will be as effective at helping Rev. Lovejoy as she has been at helping the rest of the town, she has no idea what form this help might take, and neither does he, until it occurs to both of them simultaneously in an impossible-to-anticipate act of God. He dedicates his next sermon to it:

“Baboons to the left of me. Baboons to the right … And that’s when I got mad.”

“Now that’s religion,” Homer stage-whispers approvingly to Marge, now back in her usual pew, where she belongs.

I always said the worst part about being Dear Prudence was not being able to read Dear Prudence. It’s a wonderful job, but it’s a lot more fun sitting in a pew.

__________________________________

From Dear Prudence. Used with the permission of the publisher, Harper One. Copyright © 2015 by Daniel M. Lavery.