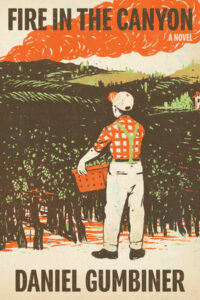

Daniel Gumbiner on Wildfires, Winemaking, and Writing Fiction

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of Fire in the Canyon

Fire season in California goes from the driest months of summer until the first rains come, if they come. (Traditionally October 31 was the date to circle.) It’s a time when people stay alert to rising winds, the smell of smoke, sirens and alerts signaling that a wildfire is on the prowl and it’s time to evacuate. Daniel Gumbiner’s immersive second novel, Fire in the Canyon (after The Boatbuilder), captures the surreal landscape of the fire zone in the Sierra foothills and how it challenges and transforms the Hecht family and their rural community. Having evacuated from wildfires in Sonoma County multiple times, I read it as a richly detailed and truly told chronicle of our times.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How have the past few tumultuous years been for you? Managing your work as editor of The Believer, which was folded by the University of Nevada, its archives sold, then resurrected after a community-driven campaign and change of ownership back to McSweeney’s with you as editor? Writing, editing and launching this new novel?

Daniel Gumbiner: They’ve been surprising and uncertain—but also quite rich. When the magazine was defunded, I really believed it was the end. So I started to look for other jobs, and was trying to think about what my next steps would be. And then there was this miraculous turn of events, where we were able to bring the magazine back to McSweeney’s, and that was an exciting, busy time. There was this outpouring of support from so many people who helped make that happen. And that was a really special thing to witness. We had a party for the first issue back and it was wonderful to see so many writerly friends all in one place. I think magazines are such important community hubs. As writers, we often operate in our isolated silos and we need excuses to come together. Like my friend Oscar Villalon said the other day: you can’t be a bohemian by yourself.

I was interested in showing how a fire might shift the social landscape of a town.

JC: How does Fire in the Canyon draw upon your own life, your early years? What was the initial spark that began the project?

DG: I think it draws on my own life in many ways—and probably in ways I don’t even realize. I remember I first saw the impact of a wildfire when I was on a bus going up to the Sierras, to summer camp, in Desolation Wilderness. I was struck by the magnitude of what the fire had done. And also, honestly, a bit terrified by it. It was one of those moments where you realize that the adults in your world can’t control everything, that there are powers larger than them.

So since I was a kid, I think I’ve had a lot of respect for wildfire. And of course, in recent years, due to the climate crisis, we’ve seen increasingly destructive fires. Almost everyone I know has been affected by them in some way—some more than others. We could all sense that something was shifting. So I wanted to write about witnessing this shift, about the experience of living in the midst of these more intense fires.

Wildfire continues to be frightening and awe-inspiring to me. I was up in Placerville at my family friend’s farm a little while ago, and he took me over to Grizzly Flats, the town that was basically entirely destroyed by the Caldor Fire. We drove around the burn in that area, where loggers are felling trees to salvage the wood. We probably drove around for three hours or so and everything you saw was burned forest. The scale of that fire’s impact is just indescribable. It is so vast.

JC: Fire in the Canyon implies no way out. At least it does for those of us who have been evacuated during wildfires or followed the trajectories of disastrous fires. Is that what you had in mind with the title?

DG: I think there are a few ways you can read it. And I like that interpretation. One of the reasons I liked the title, too, is because the canyon is a kind of boundary, to the people in the town. There’s a certain way in which they’ve understood how fire works in their community, how it interacts with the canyon. But this dynamic is shifting, and that’s part of what the characters are confronting.

JC: You introduce Benjamin Hecht, 65, a former cannabis grower (he served 18 months at Lompoc for growing medical marijuana) turned winemaker who has lived for decades in the gold country. The fire season grows worse each year, yet he persists, with a farm that needs constant tending: “ten new chickens, two dachsunds, honeybees, a small flock of sheep, one guard dog, ducks, geese, several CBD plants, one acre of Primitivo, two of Grenache, two of Barbera, three of Gamay, and three of Syrah.” (Plus two baby emus.) How were you able to capture the daily routine of the farm over the months of the novel?

DG: I spent a fair amount of time hanging out on vineyards and meeting winemakers over the course of researching the book. I have several friends in that line of work too, so I relied on them at times. But I also just read a lot. I love getting absorbed in that kind of research, reading about sheep forage or what have you. In that way I’m a bit similar to Ben. He’s someone who likes diving into these new hobbies, new interests. In his case, he’s always adding these new elements to his farm.

I think I was drawn to writing fiction, in part, because I’m a generalist in this way. If I had to study one thing, one subject, my whole life, I’d probably get bored. But writing novels allows you to move through different universes, spend time with them, and then continue on. I think my fiction writing is a kind of odd ledger of my general interests over time, as a result.

JC: Ben’s farm is near the small town of Natoma. Is this based on a real place? How did you craft the details about the Gold Rush history, the shifts in the land and in industry, the ebb and flow of rain and wind and heat, in this region?

DG: The town is fictional but it draws on some aspects of other towns in the foothills. I’ve always loved that region. It was an area we used to visit as kids, and it always had a mythic quality to me. It’s kind of a passed over place, in some ways. Most people from the city go straight through it to get to the mountains. But it’s a beautiful region and I always thought it would be an interesting setting for a novel. When I started writing about Ben moving around on his farm, I knew he was in the foothills, but I didn’t really have an idea of what kind of town he’d be in, or what the setting of the story would be, more specifically.

So I began to build out the setting in more detail as I went. I really enjoy developing the setting of a story, though it’s always a challenge. For it to work, you need to weave setting into the fabric of every scene, through all these discrete details, like you mention: climate, history, etc. I know a setting is working well when I feel like I could keep spinning a story in that world forever. I could just open another narrative thread and let it unfurl in the environment that’s been created. So that’s the feeling I’m striving for. Once I get to that point, I know the setting has depth to it.

JC: The novel unfolds as Ben, his novelist wife Ada, their son Yoel, who has stopped speaking to his dad but is visiting from Los Angeles, face evacuation as a fire comes precariously close. Your descriptions of the wind, the flames, the damage, are spot-on. Have you experienced wildfires? How many? Were you evacuated?

DG: I’ve never been evacuated for a wildfire myself. For those passages, I was relying on interviews I did, with friends and strangers, about their experiences with fires and evacuations. I also listened to a lot of oral histories about people who had been forced to evacuate. Friends would share photos and videos with me too. I really wanted to understand that experience as closely as I could. In a lot of ways, it’s the most common experience related to this crisis. Not that many people die from wildfire—though of course all these deaths are terrible—but many people are evacuated, many people lose their homes. And that is its own kind of devastation. So when I was thinking about those evacuation scenes, I tried to tap into my own experience of times when I’ve thought I might lose something really important to me. That helped me try to understand what the characters in the book might be feeling in those moments. What do you do when you’re on the precipice of that kind of grief? When you know something might be truly gone and there’s nothing you can do about it? I think that’s something we can all relate to. And unfortunately, it’s an experience that will become more common in the years to come.

JC: Fire in the Canyon could almost serve as a primer for a contemporary winemaker, as you trace the cycle of the crop, the harvest, the fermenting, and so forth. How did you learn so much about the traditional forms of winemaking in Europe, Argentina, California, as well as the new style of making natural wines, which currently fascinates those in the wine industry?

DG: I’ve always been interested in wine, but I never knew that much about it. The book was a fun excuse to explore that world in more detail. There’s something alluring and elemental about winemaking. As one of the characters says in the book, it’s kind of like midwifery: you are guiding something into existence. You take what the particular conditions of a season give you and you work with that. So you are not entirely in control—you’re responding to the natural world. I just really fell in love with the nuances of that process. Perhaps a bit too much at times…Part of the editorial process was trimming back some of the winemaking details.

I’m interested in the ways in which we can all be of use, despite our flaws or hang ups.

For Ben, I think, growing grapes and making wine is a chance for him to reinvent himself. He was a cannabis grower for years, and made lots of money doing that, but then he was prosecuted for one of his grows, and ultimately, growing cannabis was no longer an option for him. Moving onto wine felt like a natural development to me. So many of the people I’ve met in the wine world come from unusual places. Often they’ve lived many lives. I’ve met winemakers who used to be club promoters, philosophers, pharmacologists. The craft seems to attract a certain kind of searching, experimental character.

JC: The community of Natoma—the winemakers, the new bar owners, the fusty sheriff, Yoel’s high school friends and the newcomers in his life, including Halle—arrive on the scene as organically as shifts in the natural world. You describe their interactions beautifully, including the awkward moments, the long-held grudges, and the helpfulness. Halle and her friends, Argentine natural winemakers Seba and Yami Garcia, help Ben and Yoel and Ben’s old friend Wick, whose band is popular in the area, and others at harvest time. The evacuations bring people into contact, helping strangers, reaching out to friends and neighbors by text. How do you think about plotting when you’re pulling together a community devastated by fire?

DG: One of the things I wanted to show was the way in which the fire puts all these characters into relationship with each other. This was a story I heard over and over when talking to people about how fires had affected them: it connected them with their neighbors in new and surprising ways.

I was interested in showing how a fire might shift the social landscape of a town. In terms of plotting, that was definitely something I had in mind. I don’t tend to plot out my fiction too meticulously, but in this case, I did know that I wanted a fire to set in motion the different narrative threads of the book. From there it was a matter of following the characters, considering how they might change and grow in response to it.

I met a group of people, up in El Dorado County, who banded together to help protect their property from the Caldor Fire. They called themselves the Ant Hill Army. This was a group of people that really ran the gamut culturally and politically. You had people who lived on communes working side-by-side with ex-Marine Trumpers, cutting a fire line in the forest. Some of them didn’t have insurance or they had bad insurance, so they had everything on the line, in terms of saving their homes. They worked nonstop for two days straight and they were successful in stopping the fire from moving in on their properties. And they’re all still closely bonded now. They had an anniversary party where they commemorated the fire together. And one guy who I was talking to there told me that they just don’t talk about politics together. Obviously, it’s not a perfect situation, but I find stories like that inspiring.

JC: Yoel joins other younger members of the community and an activist group called the San Andreans to protest climate change and the attitudes of fossil fuel companies. Are the San Andreans based on real environmental activists in these times?

DG: No, they’re not connected to any real activists, but I think they represent something that a lot of people feel, which is that the response to this crisis is still deeply inadequate. We are dealing with an existential emergency but we all go about days as if it more or less doesn’t exist, which is pretty crazy. I think Yoel, as a sensitive person, feels the desperation of the situation quite acutely. So he is pushed to action more rapidly than others are.

At various points in the book, Yoel’s sensitivity is a hindrance to him, and the family. I think, at times, he feels like it’s a challenge he needs to overcome. But it’s also kind of the source of his strength and value to others. I think the parts of ourselves we feel we need to reject are often the most powerful. I’m interested in the ways in which we can all be of use, despite our flaws or hang ups.

JC: What are you working on next/now?

DG: I’m not sure. Have a few ideas I’m excited about but I don’t feel fully committed to any of them yet. Stay tuned!

__________________________________

Fire in the Canyon by Daniel Gumbiner is available from Astra House.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.