Danez Smith: 'Being a Poet Means Committing to Vulnerability'

In Conversation with the Author of Homie

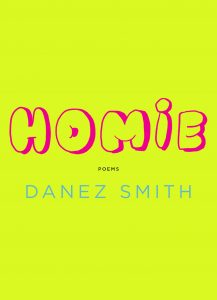

Danez Smith burst into national recognition in 2014, when their poems about the Black Lives Matter movement found piercing resonance in a time of social and political change. Smith won the Individual World Poetry Slam that year, as well as the Lamda Literary Award for Gay Poetry for their book [insert] Boy, before winning even more recognition for their subsequent book, Don’t Call Us Dead: Poems. In Homie, (which has an alternative title using a shortened version of the n-word, My N—), released in January of 2020, Smith traverses raw feelings with precision and grit and creates a work that is both deeply personal and effusive about those who are dear.

*

Sheila Regan: What does being in community mean to you?

Danez Smith: It feels natural. Being in community is the definition of being a human. Everything comes back to community and how the self is informed by that. That’s where love happens, and change happens and home happens.

SR: One of my favorite poems in the book is, “i’m going back to Minnesota where sadness makes sense.” Why did you come back? What does Minnesota have that makes you stay?

DS: I came back for family, and I was sad. I was sad as shit. I came back to Minnesota, really, because I was in California, and I had got a little bit of money from a couple of grants. For the first time in my life, I could conceivably quit my day job, be a full time artist, or try that life out for a little bit. So I quit my California job and moved back to Minnesota because living in California, that money would have gone a lot quicker. And also I was sad as hell. I was like still reeling psychologically from my diagnosis with HIV, and I think it made sense to me to move back to family and friends, to a place where I already had a sense of myself, and had a network, and had folks I could lean on. Minnesota has always been my crash pad. If shit goes too bad some place, I come back here. It’s been a place that I could put myself back together in a time when I needed to.

SR: A lot of the poems in this collection read like letters—you’re talking to a particular person. What drew you to this particular form of writing?

DS: I wasn’t like actively thinking about the epistolary form too much, but I guess, that just comes with the territory of writing a book about love, writing a book about people, is that you write to folks with an intimacy, with a specificity. Maybe it does pick up this tone of letter writing, or what it means to hone your language and your intentions towards a person or community with focus and attention.

I think letters are kind of cool. I love reading letters by writers or political heroes. You get a little peek in. It has a specific audience or audience member in mind. It’s not like the rest of us don’t know the materials of which we are eavesdropping on, we just get to feel what it feels to love someone else. So it’s fun and it’s voyeuristic and it’s all the things that you like about poetry.

SR: You tap into an incredible vulnerability in these poems, and you go to some pretty dark places. In your process, how does a poem that starts out as private get transformed into a work you are ready to share, through publishing or in another way that makes it available for other people to read?

DS: I don’t know. I don’t think I have that process. I think vulnerability is something that I’m committed to in my work. That is part of what being a poet means to me. It’s an applied commitment to vulnerability.

SR: Is craft part of that process or is it a time thing?

DS: I guess I’m not scared of being vulnerable. I wouldn’t publish it in a poem if I wasn’t able to say it in plain speech to the people that I need to say it to. But I also feel in my daily life, I don’t want to shy away from saying shit to people.

SR: When you use a form like a sonnet or another very structured way of putting the poem together, does that structure come at the beginning? Do you start out saying, “I’m going to write a sonnet,” or does it come later?

At times you start off with a bottle and you’re trying to fill it, at times you just got your water and you’re trying to find the right thing to hold it.

DS: It comes both ways. Sometimes it’s, “I’ll write a sonnet. Who cares. Let’s see what happens.” Sometimes you write the poem and then it’s already 13 lines or 15 lines. It’s already 14. And then you just lean into it. Sometimes it’s an editing tool. Sometimes the poem will be kind of large and unruly. You’ll go and say, “Let me see if I can do that same thing within a within a received form that holds it right.” And so it comes in all ways, you know? So sometimes you start off with a bottle and you’re trying to fill it, and sometimes you just got your water and you’re trying to find the right thing to hold it.

SR: The recognition of your voice as a poet coincided with the Black Lives Matter movement. You’ve spoken in interviews about conflicted feelings about the ways your work was consumed and interpreted by white media. Do you have reflections now about your role as a poet in that movement, as well as other movements?

DS: It’s just given me a lot more steadiness in how I want my work to be consumed. It’s like, whose table you sit at? Not making something that feels real and vital and urgent like a snack or something to consume. I still feel ways about that.

I’m very hesitant to call myself a poet of that movement, just because I think that implies a particular pattern, like walking alongside the organizers that I do not do. It’s more fair to say that I wrote a lot of poems that were useful to folks. I was proud in those moments to know that artists weren’t gonna be passé. It was a time when we really saw that art could be urgent, it could be responsive, and that people needed it. It wasn’t a time for art to be just for art’s sake. It could affect us and feed us as we were trying to change the world in real time.

SR: Is the dual title of your book in some ways a way to set ground rules for white readers and media interacting with your work?

DS: For sure. Not just white folks but non-black people. But definitely white folks. It was to reset the rules about assumed looking. Also, don’t be messy with this book that is going to use the n-word a lot, because it’s a word I play with. And also to address and to call attention to the layers of intimacy that exist throughout the work. We can announce who was in the room, who was thought of, who was loved upon, when these poems were being written. It’s a way to acknowledge that from the start.

SR: Do you see your poems about being HIV positive as a kind of activism?

DS: No, but somebody else can.

SR: In Homie there are a lot of poems that use the page as a medium. They seem to be designed to be experienced visually. What was that like to experiment with those visual elements?

DS: I think I’ve always liked subtly playing with that visual stuff. It doesn’t necessarily feel new for Homie. It feels like something that is a part of my toolbox. Part of how I have fun in poems, is through visual play. This one is actually less visual than I thought it would be. I thought it would have more visual stuff.

SR: Is humor something that you are conscious of inserting into your work? Or does it kind of come naturally?

DS: No, I’m conscious of it, because I want my poems to sound more like me, and I think I’m pretty funny. It’s part of a conscious effort just to try to bring more of a full sphere of myself to the work.

SR: What’s the question that you never get asked that you wish that you got asked?

DS: Not enough cuties ask me to go get tacos. You’ll have to take it up with Grindr.

SR: Where’s your favorite place to get tacos?

DS: Oh, the taco truck in the parking lot of K-Mart, El Primo.

SR: What’s next for you?

DS: Touring books and all that kind of stuff. I just got more work to do. First we’ll get Homie out into the world.

__________________________________

Danez Smith’s new poetry collection Homie is now available from Graywolf Press.

Sheila Regan

Sheila Regan is a Minneapolis-based writer. She’s a regular contributor to the City Pages and the Star Tribune, writing about arts and dance, and has written online pieces for Fusion, Salon, Complex, PRI, Pacific Standard, and American Photo magazine. She’s also a playwright and performer.