I imagine you are customed to meek and mild trees that do not want correcting. This is a story of the west so it has got western trees. You do not know the manners of our trees. I have told you that my brother and I dwell in the city of Ohio, which sits on the western bluff at the mouth of the Cuyahoga, looking across that crooked river at the city of Cleveland on the eastern bluff. Put this map in your mind.

In 1796 Connecticut surveyors come through and said that there ought to be a town called Cleveland. They did not bother any with making the town, only with drawing it on their maps. The first settlers found the place full of discouragements, such as moschitos, ague, and poorly behaved wildlife wanting chastisement.

A mule’s character were evident in the population from the first. The settlers kept on past the discouraging and their infant town Cleveland had grown up to one thousand souls by the year 1828.

Your true mule westerner does not prefer one thousand neighbors. As Cleveland grown, handfuls of folks spilled across the river looking for an emptiness more to their liking. My brother and I—orphans in the care of Mr Job and Mrs Tabitha Stiles—went among these handfuls.

In order to make a good emptiness you have got to clear land. The trees on the western bluff, having seen the demise of their eastern kin, was wary. But we only nibbled out our few acres and kept a glass-thin peace with the woods.

The trouble come when the nibbling spread out into eating-up.

As winter of 1828 cleared out, the handfuls coming across the river become sackfuls, every man among them taking his bite out of the woods. The western trees—oaks and elms and plump sycamores by the dozen thousand—whispered by breezes as their buds came in. They said We must get shut of these fleas.

Soon folks found trees sprouting up where they had just cleared ground. Plots vanished. Dead timber fell onto homesteads without any storm blowing them over. Firewood piles took to disappearing.

After a week of this awful spring, a fear settled on us. A worry that we had found the limits of the republic.We fleas fought back. I were barely ten years and too young to swing an axe to any use but I remember spring air felt as warm as summer on account of all the chopping. Every man’s axe has got a voice to it nock chsnk gntk dnnk A hundred different words saying the same meaning.

All the axe talk had romance in it but the trees was not enamored any. They only grew back faster and thicker than before. Thieved back plots already cleared. Branches were seen to bust into windows and doors and carry off animals and merchandise. Have you ever felt the breath of an angry tree? It has a cold carelessness.

After a week of this awful spring, a fear settled on us. A worry that we had found the limits of the republic. That we should stop at the eastern side of the Cuyahoga. That we had gotten to the bottom of the west. That the continent would revolt and fling us back into the ocean.

*

You have already heard the pure and pretty thwock of my brother’s axefall as he cut his way into the widow’s house. You ask why it were not heard among the choir. Is not the merest smell of Big Son enough to scare trees worse than one thousand beavers? At the year 1828 Big were not yet the hero you have met. His hair hardly shone. He had not yet learned to thwock.

When the half-child Big announced at the second Sunday of spring that he would clear the timber in two days and a night, the men fleas could only laugh. A mean type of laugh. They said they would like to see it. They said such comedy would lift their spirits. They said Go ahead and even borrowed my brother a good axe.

Before a jug could be fetched, my brother smashed into the trees, his borrowed blade curling back the edges of the air. Trees and fleas alike kept at laughter, but before any too long the comedy gone out. The timber saw that Big were no regular flea, and us regular fleas stared in wonder. Even my young eyes knew it right away. Even curious squirrels and birds and ground hogs known to stop and watch. All creation likes a miracle.

A rastle will make a crowd but it cannot keep one without enough pummeling. Boredom come on.Big knocked down a dozen trees in the first quarter of an hour, before the forest took him serious. After that brave beginning, the match turned some. A long mean locust grabbed Big up in a branch and flung him deep into the wood—where the trees stood so close you could not see the doings. Only the sounds of Big gasping and thwocking, leaves shaking, branches snapping. Here and there a flash of his blade or his hair catching the sideways afternoon sun. A tree top sinking down in defeat. A startled deer bolting.

Such commotion gone for hours on end. A rastle will make a crowd but it cannot keep one without enough pummeling. Boredom come on. The fleas drifted off to supper, the creatures went off to a more peaceful corner of the woods, and finally the sun itself made to wander off, tired of lighting an unwatched match. Only two spectators remained—myself and Mr Job Stiles.

You will meet Mr Job better in the course of matters, but let me draw him quick. He were spare and stretched out, made of knitting sticks. He wore a thin brown fringe of beard on his pointed chin and a preacherly straw hat tilted back on the crown of his head. He always spoke like he were sorry at the situation. In this case it were called for. The sounds of Big’s fight gone down to a mutter and then nothing at all. Surely he had been pummeled to surrender. Mr Job said we ought to get home for dinner, and that I ought to fetch my brother.

I will not lie—I did not care to do what Mr Job asked. I were afraid of the dark and of creatures and of finding my brother busted past mending. But I trusted and still do trust in Mr Job. I known he would not put me to work I could not stand. There were enough of the sun dripping down through leaf and branch that I could see.

That light thinned as I made my way deep and deeper into the wood. After a half mile I got to a clear and saw the very last of the light glinting off something at the bottom of a great ironwood. An axe blade. As I come closer the spring air went out of my blood and the winter ice come back in. For the second time in my life—you will know the first later on—I were looking at my brother’s dead self. The axe were tucked into his arms just like a burying Bible, with the last bit of dusk as a shroud.

Yet! As I inched toward him in despair I seen that the dusk did not shine in my brother’s hair. I seen at close examine that this were not hair at all but a clutch of twigs arranged as a wig. His skin were not skin at all but birchbark. But these were surely the britches and blouse of my brother—he had been turned to wood—this were too much—his were witches.

The air stunk of sawdust and smoke. My skin and clothes were painted all over with ashes.Just as I ran a finger over the bark of his cheek, sleep came over me like I were thrust into a sack. I slumbered hot and itching. I dreamt that I seen my brother, alive and naked as a babe, moving in and out of the timber, the blue moonlight on his rear.

*

From the light I known it were the middle of morning. What I did not know was where I were. The air stunk of sawdust and smoke. My skin and clothes were painted all over with ashes. All around me was a town I did not know, with a wide-eyed look to everything. Like it were only just born. Houses and stores and barns, all naked yellow wood. What was this place? I met our neighbors and friends—Mr Dennes and Mr Philo and Mr Ozias—straggling through, smacked dumb. I were in the same way. I could only blink and turn my head around in wonder. I would still be there stumped except I heard another MEED. This time not a whisper but a lusty holler from beyond the new buildings. Before long a scorched and still-naked Big came out of the alien lanes, dragging his axe and a wild tale.

Meed, those trees wore me to tatters. I were tossed back and forth for hours even as I cussed bad as I knew. All the time I flew across the sky my brains kept kicking At night’s coming, the trees tired of sport and set me down but left a sentry A great grandpa ironwood minded me while the forest went to its evening chores He waved the axe toward the stump what marked the ironwood. And I made a pantomime that the scrap had put me to sleep. Soon through a cracked eye I seen that the ironwood was abed too and—

I knew right then what he had done. I have always had a head for understanding Big. His pride were spilling out of him in nervous talk. Let me make you a present of the trimmed and tidy account.

*

The trees gave my brother a thrashing and expected he would sleep politely. This faith were their undoing. Once Big saw his guard-tree were dozing he slipped from liarsleep and made a liar-self from sticks and bark. He left the false Big into the arms of the ironwood, along with his axe—the thwocking of which would have woken up all the forest. Around this time I shown up and he panicked I would spoil his sneaking—so he gently knocked me over the head and laid me down next to his doll. All night he peeled and scotched and girdled, gathered up kindling. Just before the sun stirred from rest, he ran naked through the arbor and lit one hundred fires.

Dawn stirred into day and Big kept toward chewing up the whole western forest.The trees awoke to the dawn of their own burning, with the true sun hid behind the blue smoke. They panicked to find themselves trussed up by Big’s night-work. My brother did not make any deathbed sacraments for his rivals. Instead he grabbed up his axe from the hands of his false self and went wild with progress. He butchered the trees in a dozen ways. Pulling one up and swinging it as a club into another. Busting one over his knee. Sending one tumbling into its cousins like tenpins. Smiling as he went—leaving stumps and holes and busted tree-bones all over. His work were never tidy.

Dawn stirred into day and Big kept toward chewing up the whole western forest. Before too long the fleas was awake and watching—eyes following the shining hair even as the boy underneath looked more a man with every smasher. Finally he felt those flea eyes and ceased his work—huffed some—looked around at his mess—turned to the fleas—spread out his arms like an actor and said Go ahead

At first they moved with cautious wonder, sniffing and kicking at the jumbles of felled timber. But before long caution turned to greed and the fleas ran to claim up the best lots. They set straight to carpentry and knit the still-warm wood into homes and barns and stables and stores, all in a morning. And then I awoke and heard the story straight from Big—how Ohio city, the sister and rival of Cleveland, come to be.

__________________________________

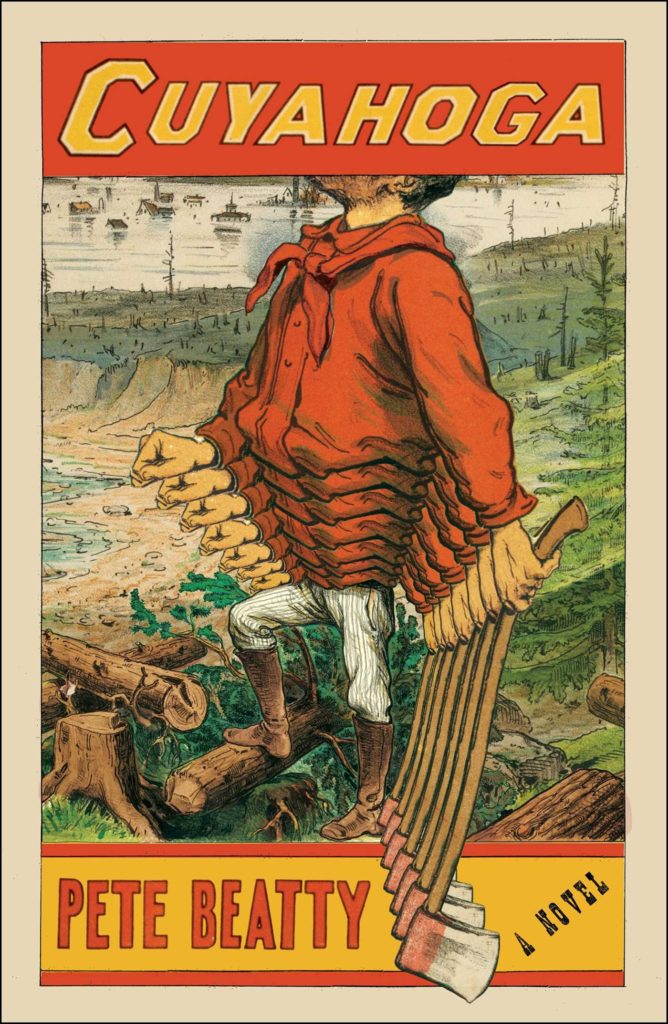

Excerpted from Cuyahoga by Pete Beatty. Excerpted with the permission of Scribner. Copyright © 2020 by Pete Beatty.