Photographs by Kelly Marshall, copyright © 2024.

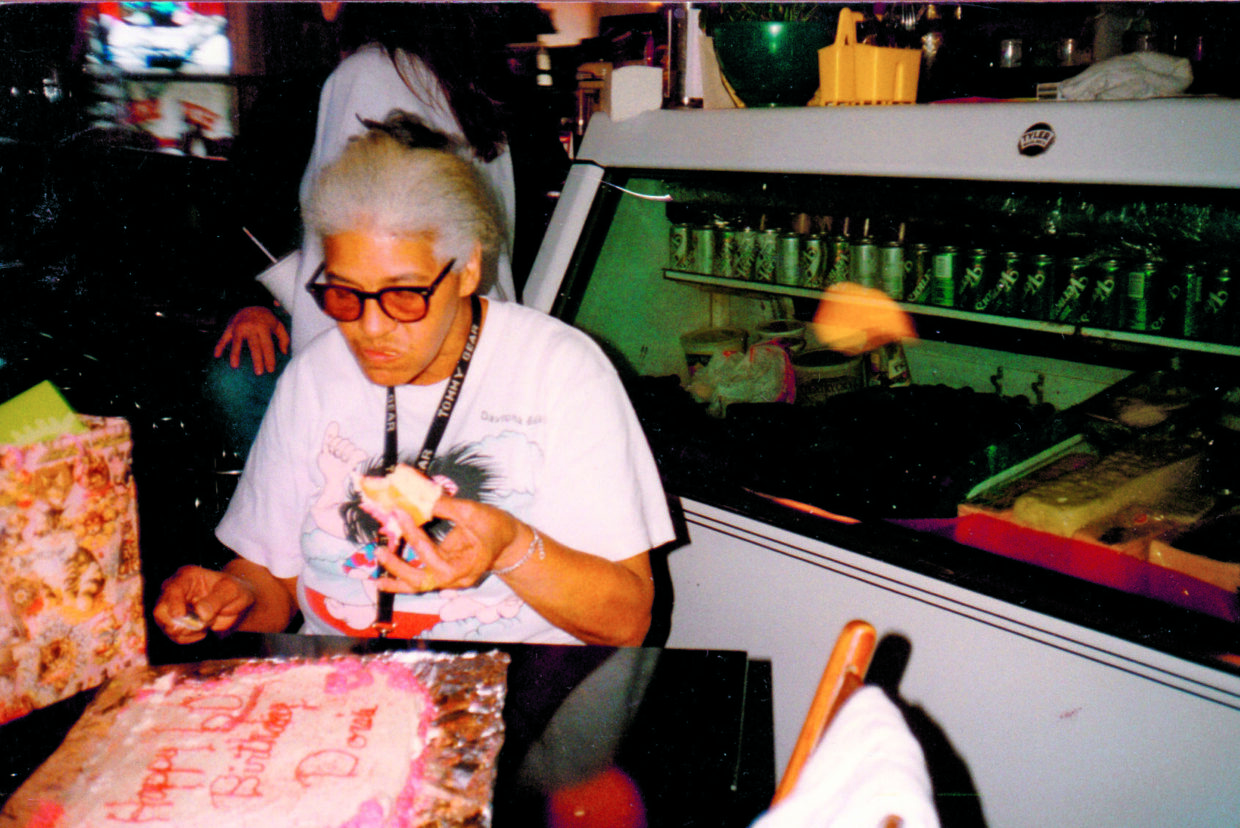

Mama always began calling as early as Christmas, letting us know that her February birthday was approaching. “I got a birthday coming up,” she’d say. I was sometimes annoyed by the frequency of her reminders, but I’d laugh and say, “I know, Mama.” This was our routine for all of my adult years on until the end of hers.

Each time I’d ask her what she wanted for a gift, she’d answer with glee, as if she were a child. Chocolate cherry cordials. A new dress for church. A blue sweatsuit with pockets. Chili. A pretty bedspread. A watch. A bar of chocolate. An amethyst birthstone ring. Pickled bologna. A mess of fish. Pickled eggs. She’d name one thing or a dozen things she wanted and then she’d say, “Oh, I don’t want nothing. I just wanted you to know my birthday’s coming up.” She did this every year.

Black people where we’re from didn’t celebrate birthdays much. We weren’t a time-conscious people back then. We kept time by the sun and the moon and when work needed doing, even after the Industrial Revolution brought watches and clocks to nearly every home. It has been only a few generations since our enslaved ancestors weren’t allowed to know their birthdays or even keep track of their ages to perpetuate the idea that they were property, not people, so maybe this birthday celebration idea needed time to catch on.

By the time I came along, my grandparents still weren’t accustomed to marking birthdays. They’d raised their children as they worked alongside them in the fields. The workday and the tasks ahead for survival were more important than any solitary day or any solitary person. They worked as a cooperative unit, and the only days celebrated were holy ones. But still, through the years, there was an occasional card, a favored dish cooked, and a quiet-spoken “Happy Birthday.”

By contrast to the old ways, I grew up in a time of little white children with pointy party hats and fancy cakes on television and in magazines. My white friends from school had slumber parties and cakes with candles and finger foods in their honor. They were showered with presents wrapped up like Christmas gifts, but we didn’t do that in our house.

*

Mama was born in 1939 into a family that would include seven siblings. Children were considered economic assets more than they were emotional assets, though I know my grandparents loved all of their offspring. When I asked Aunt Lo what she remembers about birthdays, she said it was just like any other day. I’m sure my mother’s childhood was the same, but as an adult, Mama reveled in being celebrated, if only for one day. She liked a big fuss made with candles and store-bought cakes and dinners out to restaurants in her honor, and now that she’s gone, I wish we’d made a big fuss about her birthday a little more.

*

I had one childhood birthday party when I was twelve, likely because of my whining for a party and wrapped presents like the white children. That July, my grandmother bought party hats from the dime store. She put a plastic tablecloth with balloons over the dining room table and cooked hamburgers and hot dogs on a grill right outside the kitchen door.

Though cooking food over an open fire in pots was still common during hog-killing time, this idea of grilling food outside was also something new to us. We’d seen this on television, but our people were not the kings and queens of the cookout; that was a thing in locations farther south. Cousin Loretta was the only attendee. We blew into little plastic horns that must have been included with the hats as my grandmother lit the candles on my angel food birthday cake. I blew out the candles. We clapped.

It was fun for about fifteen minutes, but I can’t recall that any of it gave me what I thought I saw in the magazines. We played badminton in the backyard, tried our hand at pin the tail on the donkey, went down to the creek to swim. We floated downstream on inflatable loungers that had taken half the day to blow up. Then the partying was over. My birthday done.

For my son Gerald’s ninth birthday, I invited eight little boys to our duplex for a sleepover. I made three gallons of red Kool-Aid in a container with a spout, and they drank from it all night as if I’d organized a keg party for rambunctious boys. I served limp pink hot dogs on cheap buns and offered a piddly squirt of yellow mustard or ketchup as they skipped, jumped, twisted toward the table. They ate on paper plates, and I let each of them dig their hands into a family-size bag of chips to complete the birthday meal. They punched each other in the arm and wrestled on the floor.

For dessert, I served a mushy slice of ice cream cake that I had bought at Dairy Queen, which became a family tradition for a few years, well past the time that his twin sisters were born and had become teenagers. I wanted my children to feel celebrated. I broke my budget on the party. Some of the boys’ mothers bought gifts for my son. I bought gifts for Gerald, too, though I can’t remember what they were.

What I remember most is the red circular stain on my carpet that blossomed underneath the Kool-Aid decanter and plate after plate of melting ice cream cake, the boys hopping over discarded plates strewn on my living room floor and in my son’s bedroom like lily pads. Late that night, when the boys should have been asleep in the sleeping bags, on the bed, on the pallets I’d made on my son’s bedroom floor, they slipped into the kitchen and got into a canister of popcorn.

The next morning there was popcorn all over my son’s bedroom as if confetti had been thrown. I never quite understood the art of children’s birthday parties, but I knew I wanted to try. I wanted them to feel celebrated.

*

Mama glowed on her birthdays. She sat in her senior citizen high-rise apartment and received cards from her neighbors and relatives like a queen. She taped a long trail of birthday cards to her door for all to see. We took her to all-you-can-eat buffets. We bought gigantic cards for her that played music or featured a pop-up scene and a saccharine message when she opened them. We bought roses, pink carnations, dresses, heart-shaped ashtrays, and bowls that declared her to be the best mother/grandmother in the world.

She bought diamonds for herself. I baked pies and cakes for her. Cooked her special dinners and some years simply sat in her company while she basked in her glory. I baked an apple spice cake for her once that was made with artificial sweeteners. She retaliated by eating a half gallon of butter pecan ice cream when she got home. It was her birthday, she told me. “I can eat what I want.”

I never quite understood the art of children’s birthday parties, but I knew I wanted to try. I wanted them to feel celebrated.Cousin Trish says she’s had two birthday parties in her life—one at sixteen and another at forty. Her sweet sixteen party has held firm in my memory all these years; I could have been no more than seven. It seemed a grand affair to me back then, though of course the memory blends with the imagination. Trish in her new dress, looking like a movie star.

The party was put on for her by Miss Margaret from their church. I’m not sure why Miss Margaret hosted the party and not my aunt and uncle, but me and my other little cousins were underfoot. There were tables of food like a Southern summer soirée—mounds of sandwiches on a great long table and a punch bowl filled with something cold, sweet, and tart, made, I believe, from sherbet and lemon-and-lime pop.

That day began my decades-long love affair with pimento cheese, but there was also Benedictine and chicken salad sandwiches with the crusts trimmed off and small bowls of butter mints and peanuts. There was music. It was the ’70s and everything was awash in pastels. What I remember most is Trish’s smile while she stood in the middle of that milestone that August, her future glittering in front of her as all of us bore witness, celebrated, and ate the fancy food.

*

For my twin daughters, I took a different route, having learned my lesson with their brother. I saved up for their birthday parties even though my money was tight. I rented two adjoining rooms at a cheap hotel with a pool. I stuffed a cooler with a variety of drinks no one else wanted from Big Lots’ sale table and bought pizza and bags and bags of odd clearance snacks that none of the children had ever heard of (Big Lots, again). I bought one ice cream cake with both their names written in icing on it and set their guests loose in the pool until they were so tired they fell asleep in wet piles of girl giggles across beds that smelled of chlorine.

Stained carpets, plastic palm trees, nightstands with cigarette burns in the faux wood, calling hotel security on unsavory characters lurking in the hallways, my friend Sue Bonner volunteering every year as chaperone and bouncer. My girls remember these birthdays as the times of their lives.

During a family discussion about birthdays, I tell my adult children that our ancestors didn’t celebrate their birthdays and that if you go even further back, they weren’t allowed to. “Let’s honor each other,” I tell them. Let us celebrate. Not in a way that is meant to milk our pocketbooks in the name of consumerism and capitalism, but with love. I ask them each to name a birthday meal and an accompanying dessert.

Ron, my husband, says soup beans and cornbread and chocolate cake.

Gerald, my oldest son, says pot roast (I knew he would) and a homemade ice cream cake.

Elainia, one of the twins, says meatloaf, mashed potatoes, green beans, and pineapple upside-down cake (I knew she would).

Delainia, the other twin, says spaghetti with garlic toast and angel food cake with whipped cream and strawberries.

Journey, my bonus daughter, and I share a birthdate. She says breakfast with pancakes with crispy edges and yellow cake with chocolate icing.

Isaac, my bonus son, says, “Let me think about it,” but he never gets back. He’s a college student and well… he’s a college student. I’ll ask him in a few years when he’s less distracted.

Me: Give me a good burger with potato salad, baked beans, and greens with Aunt Edith’s Hot Milk Cake.

*

Comedian KevOnStage says in a popular online video, Black people love celebrating birthdays. I don’t know about other cultures and people; I’m sure they do but Black people, we really go hard for the birthday. Let me tell you, if my birthday falls on a Wednesday you can guarantee I’m having a birthday celebration the weekend prior and one after. My birthday will have come and gone and I’m still celebrating. We’ll celebrate all month like a Roman emperor.

He goes on to mention that we will plan something every day of the week or the month to celebrate our birthdays: white parties, photo shoots, special gifts for ourselves, and he’s right. I’ll go get a spa treatment, manicure, pedicure, go to the hair salon, buy books and other gifts for myself in celebration.

I deserve it. We deserve it.

*

In Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Douglass writes, “I do not remember to have ever met a slave who could tell of his birthday. They seldom come nearer to it than planting-time, harvest-time, cherry-time, springtime, or fall-time. A want of information concerning my own was a source of unhappiness to me even during childhood. The white children could tell their ages. I could not tell why I ought to be deprived of the same privilege.”

Douglass would later choose a birthday for himself of February 14, which also happens to be my mother’s birthday (and also my uncle Glen’s birthday). That’s not to say Mama knew this. She grew up in a time when her education lacked Black history. As smart as she was, I’m not sure she even knew of Frederick Douglass or his contributions to the lives of Black people. But she certainly knew of the importance of the celebration of the self. How important it was to mark another trip around the sun. How exhilarating and affirming it feels to be celebrated on the day of your birth.

*

Angel Food Cake

This cake has been in my dessert repertoire since high school. It is as spongy and fluffy as a cloud, and it’s fat-free. Serve it plain, simply dusted with confectioners’ sugar, or paired with berries and whipped cream. To ensure maximum lift, make sure your 10-inch tube pan is grease-free and your egg whites contain no trace of yolk.

Serves 12 to 14; makes one 10-inch cake.

1½ cups confectioners’ sugar

1 cup cake flour

12 large eggs, at room temperature

1½ teaspoons cream of tartar

1 cup granulated sugar

⅛ teaspoon table salt

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

Sift the confectioners’ sugar with the cake flour onto a sheet of wax or parchment paper. Repeat two more times.

Move the center oven rack down one notch and preheat the oven to 325°F.

To separate the egg whites from their yolks, crack the eggs one at a time into a small bowl. Lift out the yolk and place it in a separate container with a little water in it (see Tip), and pour the whites, one at a time, into a 2-cup measuring cup. You need a total of 1½ cups of totally yolk-free egg whites.

Pour the egg whites into the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with a whisk attachment or a mixing bowl and use a handheld mixer. Beat on medium-low speed until frothy, then sprinkle in the cream of tartar. Beat on medium-high speed until glossy, soft peaks form.

Sift or gradually spoon small amounts of the granulated sugar into the egg whites, beating at medium-high speed as you go and maintaining the beaten peaks. Add the salt and vanilla, beating to incorporate. Remove the bowl from the mixer.

In three additions, use a flexible spatula to fold in the sifted confectioners’ sugar–cake flour mixture to create a soft batter. Do not overmix. Transfer to your tube pan, spreading the batter gently and evenly. Bake on the repositioned rack for 40 to 45 minutes, until the surface is lightly browned, with some wide cracks. Invert the cake, still in its pan, on a wire rack or with its center tube set on the long neck of a sturdy bottle to cool. Once it’s completely cooled (at least 1 hour), run a thin knife around the cake’s edges to dislodge it.

Tip: Leftover yolks from this recipe can be refrigerated with a little water in an airtight container for up to 2 days. Use them to make mayonnaise, hollandaise sauce, lemon curd, ice cream, crème brûlée, and more.

__________________________________

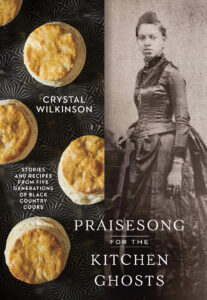

Reprinted with permission from Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts: Stories and Recipes from Five Generations of Black Country Cooks by Crystal Wilkinson. Copyright © 2024. Available from Clarkson Potter, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.