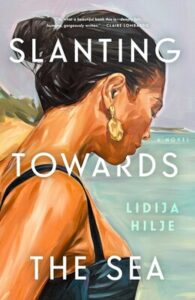

Croatia as a Character? Lidija Hilje on Trying—and Failing—to Write a Universal Story

“Even though I did my best to tune out Croatia, this proved to be an impossible task.”

Even though I’m Croatian—as in born, and raised, and living here all my life—I set the first book I ever wrote in the United States. Just like cinematography and music from a particular place tend to have a distinct flavor—a singular way of expression as well as common themes, so does literature. Croatian literature, at least back then, was largely dominated by historical and war traumas, and the storytelling was often deeply mired in irony, satire, and even cynicism; oftentimes relying on shocking the reader in order to hook them or evoke emotion.

The stories I wanted to write didn’t fit this mold. I was drawn to a subtler landscape—exploring human relationships through introspection, memory, and everyday interactions, where small moments can carry profound emotional weight, the past lingers in the present, and people are flawed, yet deeply human.

I feared that, by setting my book in Croatia, its cultural and societal backdrop would become an overwhelming noise.

For a quiet narrative like this, it felt necessary to tune out anything that might overpower it, and I feared that, by setting my book in Croatia, its cultural and societal backdrop would become an overwhelming noise, distracting from the subtle interpersonal conflicts I wanted to focus on.

So, I set my book in the United States, even though I’d never personally been there. I made my characters American, and with that I felt like I had a clean slate—I could explore the complexities of human relationships without cultural interference. After all, the American culture is so globally familiar it fades into the background, allowing the emotional core of the story to take center stage. At the time, and this was before the publishing world had made a big push for diversity, it felt like an unspoken rule that the intimate human stories—the kind I wanted to write—could only ever be American or British.

It didn’t help that I was in a phase in my life where I felt deep resentment toward my country. Reaching our mid-thirties, both my husband and I had peaked career-wise. He was a software engineer; I, an attorney at law; and between the two of us, we were struggling to make ends meet. In Croatia, even the most esteemed professionals, like judges or neurosurgeons, earned barely more than retail workers. We realized that our wages, though insufficient to support our family of four, were already the best they would ever get, and all we could expect going forward was an occasional raise that would barely curb the rising inflation. For a while, we considered leaving the country, but instead, my husband found remote freelance work that finally paid decently. As an attorney trained in domestic law, I couldn’t do the same, so I ended up pivoting entirely. I abandoned the career I had worked toward for over fifteen years, and trained to become a certified book coach, working with writers in English as my second language. Our family never physically left Croatia, but in every other sense, we didn’t belong to the country we were living in anymore.

But setting a book in a country I had never visited, no matter how many movies I’d watched and how much I’d been exposed to its culture, made it difficult to portray it in a lifelike way. Despite all my research, I couldn’t make the book feel as textured and rich in detail as I would’ve liked, and after a few years, I ended up putting that project away. For a while I focused on coaching other writers on their novels. Perhaps it wasn’t in my cards to be an author after all, I thought.

But as much as I enjoyed working on my clients’ books, not having my own project to work on gnawed at me. With time, this became a physical pain, a knot in my chest I could not let loose or untangle. As I began writing what is now my debut novel, Slanting Towards the Sea, I knew I couldn’t expose myself again to the struggle of setting it in a place I couldn’t fully bring to life. It was enough of a challenge that I was writing it in a foreign language, I couldn’t afford to complicate things for myself in yet another way. So I set the book in my hometown, the place I knew innately and intimately, hoping that I could find a way to make it seamless, to mute it to the point of complete irrelevancy.

But even though I did my best to tune out Croatia, this proved to be an impossible task. As I was writing, it became clear how much the lives of my characters had been affected by the place they called home. Just like the olive trees are shaped by the harsh winds, droughts, and vermin, the people here are molded by the shifting political climate, the cultural milieu, and the seasonal winds. Croatia tinted my protagonist’s story in the ways I hadn’t foreseen—it stifled her success, put obstacles in the way of some of her deepest desires, and knocked her down, repeatedly. And in other times, it exhilarated her with its bountiful beauty, infused her with gratitude for its well-worn traditions, nourished her with its soulful food. In other words, it touched her and shaped her in all the ways it has touched, shaped, and molded me.

As I was writing, it became clear how much the lives of my characters had been affected by the place they called home.

It was well into writing my novel that I’d realized I had been naïve to think that I could keep my country on the sidelines. Moreover, I had been naïve to think that there is such a thing as a “seamless humanity”—that any setting, even one as well-known and with a culture so dominant as the American or British—can truly be seamless. We are all heavily shaped by the circumstances and the environment we were born and raised in, and where we are trying to make our life. Some settings just need a little more set-up and context to be truly brought alive on the page than others.

As I continued drafting, and then revising my book, I ended up leaning even more heavily into all things Croatian. Not the way the tourists might (want) to see it, but in a way that felt true to what our life here really is. I set out to evoke the haunting atmosphere of the empty stone-paved streets in wintertime, the melancholy of olive groves that sway with the bura wind, fingers reddened as you pick the fruits in November. The joyful camaraderie during Advent. The quiet delight of buying roasted chestnuts from the vendor by the town bridge in the dark and cold evenings in January. Going to town on foot when the sap shyly starts climbing up the trees in March, and sitting in one of the coffeeshops, soaking up the sun. The bewildering bureaucracy that seeps into our lives, and feels like one of those dreams when you’re trying to run but your feet stay mercilessly glued to the ground. The beauty and pain and joy of it all.

For a writer, it’s often impossible to see your book objectively, so it was only when other people started reading Slanting Towards the Sea—my critique partner, my agent and editor, and then book bloggers, and readers—that it became clear just how much Croatia had emerged as a character in its own right. Central and undeniable, beautiful and formidable, and oftentimes frustrating. Flawed, in other words, but deeply human, as I strove for all my characters to be.

__________________________________

Slanting Towards the Sea by Lidija Hilje is available from Simon & Schuster.

Lidija Hilje

Lidija Hilje is a Croatian novelist and certified book coach. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times and other outlets. After ten years of trying cases before Croatian courts, she obtained a book coaching certification and has been working professionally with writers ever since. She lives in Zadar, Croatia, with her husband and two daughters. Slanting Towards the Sea is her first novel.