Colin Kaepernick on the Link Between Abolition and Black Liberation

“It is only logical that systemic problems demand systemic solutions.”

In the wake of the state-sanctioned lynchings of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and countless others, the United States has been forced to grapple with not only the devastation of police terrorism, but also the institutions that constitute, enhance, and expand the carceral state. In response, movements that demand the defunding of the police have spread across the country with no signs of stopping.

Those who have been terrorized by law enforcement, who have had enough of their very existence being criminalized, and who have dedicated their lives to the cause of liberation by any means necessary are demanding the abolition of the carceral state—the institutions, structures, and practices of anti-Black state-sanctioned violence that violate the fundamental humanity of Black and Indigenous people, and people of color.

It’s been five years since I first protested during “The Star-Spangled Banner.” At the time, my protest was tethered to my understanding that something was not right. I saw the bodies of Black people left dead in the streets. I saw them left dead in their cars. I saw them left dead in their backyards. I saw Black death all around me at the hands of the police. I saw little to no accountability for the police officers who had murdered them. It is not a matter of bad apples spoiling the bunch but interlocking systems that are rotten to their core and are authorized to kill Black people and other communities under the pretense of “justice.”

Modes of reformist and reactionary “justice” fail to remedy the uninterrupted deaths caused by policing and prisons and frequently leave us disheartened, disjointed, and disillusioned.

It is only logical that systemic problems demand systemic solutions.

Predictably, the political mainstream has responded to political uprisings by shifting the demands to “defund the police” to reformist interventions centered on “acceptable” modes of enacting death and violence upon oppressed peoples. As such, conventional paths and strategies for achieving “justice” for anti-Black police terror and violence are all too often couched in campaigns and desires for convictions, punishment, and incarceration. These modes of reformist and reactionary “justice” fail to remedy the uninterrupted deaths caused by policing and prisons and frequently leave us disheartened, disjointed, and disillusioned.

Despite the steady cascade of anti-Black violence across this country, I am hopeful we can build a future that imagines justice differently. A future without the terror of policing and prisons. A future that prioritizes harm reduction, redemption, and public well-being in order to create a more just and humane world.

To understand the necessity and urgency of abolition, we must first understand the genesis and histories of the institutions and practices we must abolish.

*

The central intent of policing has and continues to be to surveil, terrorize, capture, and kill marginalized populations, specifically Black folks. In her edited collection, Imprisoned Intellectuals, Joy James put the United States under the magnifying glass. “The world can see what goes on in the tombs of America as Black people are being slowly strangled and suffocated to death,” she writes.

When the world witnessed the police choke Eric Garner to death as he gasped, “I can’t breathe”—that is an act of terror. When a cop car pulled up to Tamir Rice, a twelve-year-old boy, and the cop shot him in less than two seconds—that is an act of terror. When police broke down ninety-two-year-old Kathryn Johnston’s front door, unloaded thirty-nine rounds, and left five bullets buried in her body—that is an act of terror. We recognize this as anti-Black violence and control while law enforcement and the injustice system see it as essential to the very nature of the job.

In order to eradicate anti-Blackness, we must also abolish the police. The abolition of one without the other is impossible.

The political project of anti-Blackness has always been central to the enforcement of laws and legal codes in the United States. Sally E. Hadden’s Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas lays out an irrefutable case that slavery and policing are linked both in logic and philosophy. South Carolina’s 1701 “Act for the Better Ordering of Slaves” declared that any enslaved African “resisting” a white person could be beaten (like Rodney King in 1991), maimed (like Jacob Blake in 2020), assaulted (like Marlene Pinnock in 2014), or killed if they “resisted” (like Korryn Gaines in 2016) or took flight (like Rayshard Brooks in 2020).

The more that I have learned about the history and evolution of policing in the United States, the more I understand its roots in white supremacy and anti-Blackness. Black Panther Party co-founder Huey P. Newton once said, “The police are in our community not to promote our welfare or for our security or our safety, but they are there to contain us, to brutalize us, and murder us.” The omnipresent threat of premature death at the hands, knees, chokeholds, Tasers, and guns of law enforcement has only further engrained its anti-Black foundation into the institutions of policing. In order to eradicate anti-Blackness, we must also abolish the police. The abolition of one without the other is impossible.

*

As part of the reentry work I have done with Kevin Livingston from 100 Suits for 100 Men4 at Rikers Island, I have spent time with young Black men in the facility no older than twenty. The young men explained the prison’s dehumanizing conditions that range from denial of literature to physical assault. They have been criminalized and caged, in most cases, for attempting to resist being redlined into economic despair.

Forever emblazoned in my memory are the words of one of the young Black men: “You love us when no one else does.”

Forever emblazoned in my memory are the words of one of the young Black men: “You love us when no one else does.” The young brother was seeking love. He was seeking care. He was seeking a space that valued his life. What he received was hate and what abolitionist scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore would call “organized abandonment.”

As Angela Y. Davis has written, “prisons do not disappear problems, they disappear human beings.” Prisons do not contain a “criminal population” running rampant but rather a population that society has repeatedly failed.

Uprisings in response to the hellish conditions Black folk have been forced to live in, both in and out of prison, have been criminalized as well. In her book Are Prisons Obsolete?, Davis effectively analyzes the purpose of prisons. “These prisons represent the application of sophisticated, modern technology dedicated entirely to the task of social control,” she writes, “and they isolate, regulate, and surveil more effectively than anything that has preceded them.” An institution based on social control instead of social well-being is an institution that needs to be abolished.

*

I recently revisited the 2016 postgame interview when I was first asked about not standing during “The Star-Spangled Banner.” One of the reporters inquired about the reasoning behind my dissent. “There’s a lot of things that need to change,” I replied. “One specifically is police brutality. There’s people being murdered unjustly and not being held accountable. Cops are getting paid leave for killing people. That’s not right. That’s not right by anyone’s standards.”

Unconsciously, my critique of police terrorism was fastened to a reformist framework. My want for accountability focused on the cops receiving convictions and punishment, not acquittals and paid vacations. But I had missed the larger picture. The focus on individual punishment will never alter the outcome of a system rooted in Black death. I wanted change. I wanted it to stop. I wanted to reform what I saw. Yet, the reforms often proposed—use-of-force policies, body cameras, more training, and “police accountability”—were the same recycled interventions consistently proposed in the past. And in both the past and the present, these reforms have done nothing to stop the actions that force us to #SayTheirNames.

Similarly, suggested prison reforms—new jail construction to address crowding and dehumanizing living conditions and technological monitoring that essentially creates open-air prisons—have not and cannot eliminate the harm of the carceral state. The thread that ties all of these reforms together is the increased investment of capital into the carceral apparatus. In a recent interview on the geographies of racial capitalism, Ruth Wilson Gilmore said that “capitalism requires inequality, and racism enshrines it.” It made me think about the economies of exploitation, deprivation, and captivity that propel forward incarceration and the construction of prisons. These economies disproportionately target Black, Brown, and poor white people. It made me think about how the carceral state is central to the machinery of racial capitalism.

I began to ask myself the question “What is being reformed or reformulated?”

Ultimately, I realized that seeking reform would make me an active participant in reforming, reshaping, and rebranding institutional white supremacy, oppression, and death. This constant re-interrogation of my own analysis has been part of my political evolution.

“One should recall that the movement for reforming the prisons, for controlling their functioning, is not a recent phenomenon,” Michel Foucault wrote in Discipline & Punish. “It does not even seem to have originated in a recognition of failure. Prison ‘reform’ is virtually contemporary with the prison itself: it constitutes, as it were, its programme.” Reform, at its core, preserves, enhances, and further entrenches policing and prisons into the United States’ social order. Abolition is the only way to secure a future beyond anti-Black institutions of social control, violence, and premature death.

*

Abolition is a means to create a future where justice and liberation are fundamental to realizing the full humanity of communities. Practices of abolitionists are focused on harm reduction, public health, and the well-being of people. Demands to defund the police and prisons are one of the ways to first realize the goals of investing in people and divesting from punishment and, in time, progress to the complete abolition of the carceral state, including police and policing.

To be clear, the abolition of these institutions is not the absence of accountability but rather the establishment of transformative and restorative processes that do not depend upon anti-Black institutions rooted in punitive practices. By abolishing policing and prisons, not only can we eliminate white supremacist establishments, but we can create space for budgets to be reinvested directly into communities to address mental health needs, homelessness and houselessness, access to education, and job creation as well as community-based methods of accountability. This is a future that centers the needs of the people, a future that will make us safer, healthier, and truly free.

Another world is possible, a world grounded in love, justice, and accountability, a world grounded in safety and good health, a world grounded in meeting the needs of the people.

Abolition now. Abolition for the people.

_______________________________________________________

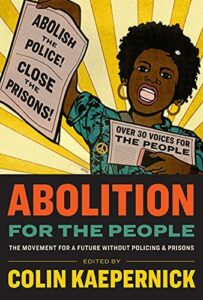

From Abolition for the People: The Movement for a Future Without Policing & Prisons, edited by Colin Kaepernick. Used with permission from Kaepernick Publishing.

Colin Kaepernick

Super Bowl QB Colin Kaepernick, and holder of the all-time NFL record for most rushing yards in a game by a quarterback, took a knee during the playing of “The Star Spangled Banner” in 2016 to bring attention to systemic oppressions, specifically police terrorism against Black and Brown people. For his stance, he has been denied employment by the league. Since 2016, he has founded and helped to fund three organizations—Know Your Rights Camp, Ra Vision Media, and Kaepernick Publishing—that together advance the liberation of Black and Brown people through storytelling, systems change, and political education. Kaepernick sits on Medium's Board and is the winner of numerous prestigious honors including Amnesty International’s Ambassador of Conscience Award, the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Ripple of Hope honor, GQ Magazine’s “Citizen of the Year,” the NFL’s Len Eshmont Award, The Sports Illustrated Muhammad Ali Legacy Award, the ACLU’s Eason Monroe Courageous Advocate Award, and the Puffin/Nation Institute’s Prize for Creative Citizenship. In 2019, Kaepernick helped Nike win an Emmy for its “Dream Crazy'' commercial.