Clare Pooley on Writerly Perseverance and Knowing When To Give Up

“You must never give up on writing itself. But sometimes you need to give up on what you’re writing.”

We’re often told that the key to becoming a published author is perseverance. “A professional writer,” according to Richard Bach, “is an amateur who didn’t quit.”

It takes a certain type of dogged determination—some might call it self-delusion—to get up before dawn for days, months, years on end and drag approximately 90,000 words out of your imagination onto a blank computer screen.

When I sat down to write my second novel, I thought that this time it would be easier. I knew I could do it—my debut, The Authenticity Project, had been a New York Times bestseller—and I already had fabulous publishers, in New York and London, waiting eagerly for the manuscript. No more wild flinging of submissions, with increasing desperation, into the farthest regions of the world wide web for me. Oh no.

The creative muse, it transpires, saves her most hysterical laughter for those of us who think it’s going to be easy.

As before, I had a rough story mapped out and a full cast of characters, so I typed CHAPTER ONE with a mixture of trepidation and excitement. Each morning, at 5am, I sat down at my desk and wrote at least one thousand words, waiting for the magic to happen—that moment when the characters you’re developing take on a life of their own and start showing you where to go. But it didn’t come. It felt like I was placing my actors onto the stage each day, feeding them their lines and telling them what to do, but their performances were surly and wooden, and they refused to improvise.

In despair, I re-read Steven King’s On Writing. King waggled his stern index finger at me, and said “Stopping a piece of work just because it’s hard, either emotionally or imaginatively, is a bad idea. Optimism is a perfectly legitimate response to failure.”

Perhaps, I thought, channelling as much of King’s optimism as I could muster, it’s hard because I’ve become a better writer. Thomas Mann believes that “a writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people,” and Hemingway says “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.”

Perhaps the story I told myself and others about the experience of writing my debut was as imagined and well edited as the debut novel itself.

It was possible I’d just forgotten how hard it was last time. Maybe my memories of those mornings feeling as if I were just a conduit for a story which was desperate to be told, my fingers barely keeping up with the thoughts which sounded in my head like dictation, were an illusion. I am, after all, a storyteller. Perhaps the story I told myself and others about the experience of writing my debut was as imagined and well edited as the debut novel itself.

So, I sat down at my laptop, feeling grateful that at least it wasn’t a typewriter, and bled. For months I forced my reluctant actors to show up on stage each day and perform. Until, finally, I typed the words THE END.

I felt relief at having finished the damn thing, but I didn’t feel elation. And I honestly had no idea how good, or how bad, it was. I mustered as much courage as I could and sent it to my editors. Then I waited. And the optimism gradually seeped away until, finally, a response.

It was very kind. It praised my writing and said there was much about the story I’d submitted to like. But then, the word we all know is coming, However…

There was a lot after the however, and it struck me that the terse, one line, rejections of old were in many ways a kindness. There were issues with the characters, with the plot and, to top it all, the whole premise. But, with work—a lot of work—it could be fixed.

I’m not averse to hard work, but the thought of pulling that manuscript back up from the depths of my hard drive where it had been skulking filled me with despair. I understood what needed to be done, and I knew I could do it, but I had a premonition that after another year of work the response, from both my editors and myself, would be little better than meh.

I remembered the Robert Frost quote: “No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader. No surprise in the writer, no surprise in the reader.” I write stories that are intended to make the reader feel good. Hopeful. Up-lifted. Surely, I thought, if I don’t feel any joy in the experience of writing, there won’t be any joy in the experience of reading?

By this time, we were several months into repeated lockdowns, and it was difficult to find much joy in anything. I really missed people. Not just friends and family, but strangers. I missed crowds of people, swarming, mask-less humanity. I even missed my daily commute.

Gradually, a story began to emerge about a group of people who share the same train line each day. Every time I sat down to re-write the novel I was supposed to be writing, this new idea would elbow its way into my thought process, its characters jostling to be seen.

That, I realized, was the story I wanted to write. The story I had to write. Not for my publishers, not for potential readers, but for me. Because I was desperate to spend time back in 2018—a happier, more innocent time. I wanted to connect with strangers and to find the kindness in random connections. I needed to feel hope.

If I abandoned those 80,000 words I’d bled onto the page now, it would mean admitting, to myself and my publishers, that the last twelve months had been entirely wasted.

For I while I felt paralyzed. If I abandoned those 80,000 words I’d bled onto the page now, it would mean admitting, to myself and my publishers, that the last twelve months had been entirely wasted. It would mean feeling, and looking, like a failure. It would mean staring again at a blank page.

Like a woman embarking on a wild affair before deciding whether to leave her dreary husband, I scheduled a few tentative dates with my new novel. Within days I began to feel the energy and obsession of a new love. Within weeks, the characters I’d been crafting started to surprise me, deviating from my script and becoming increasingly complex and nuanced. I almost wept with relief.

I was ready for the divorce.

I threw all the manuscripts of the original novel into the recycling, waiting to feel sorrow and regret, but they didn’t come. There are still drafts lurking on my hard drive, not because I’d ever want them to see the light of day, but because one day I might have the courage to look back and learn something from them.

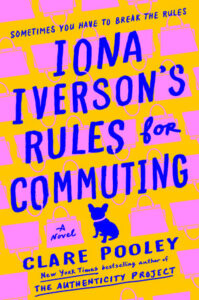

It only took four months to write the first draft of Iona Iverson’s Rules for Commuting. This time it came easily. This time it felt right. This time, thank goodness, the response from my editors was more than enthusiastic.

In my case at least, the cure for the tricky second novel was to ditch it and move straight onto the third.

The key to being a successful novelist is, I still believe, perseverance. But you also need to know when to quit.

You must never give up on writing itself. But sometimes you need to give up on what you’re writing. To paraphrase the serenity prayer: God grant me the serenity to accept the stories I cannot change, the courage to change the stories I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.

__________________________________

Iona Iverson’s Rules for Commuting by Clare Pooley is available from Pamela Dorman Books/Viking, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Clare Pooley

Clare Pooley graduated from Cambridge University, and then spent twenty years in the heady world of advertising before becoming a full-time writer. Her debut novel, The Authenticity Project, was a New York Times bestseller, and has been translated into twenty-nine languages. Iona Iverson’s Rules for Commuting is her second novel. Pooley lives in Fulham, London, with her husband, three children, and two border terriers.