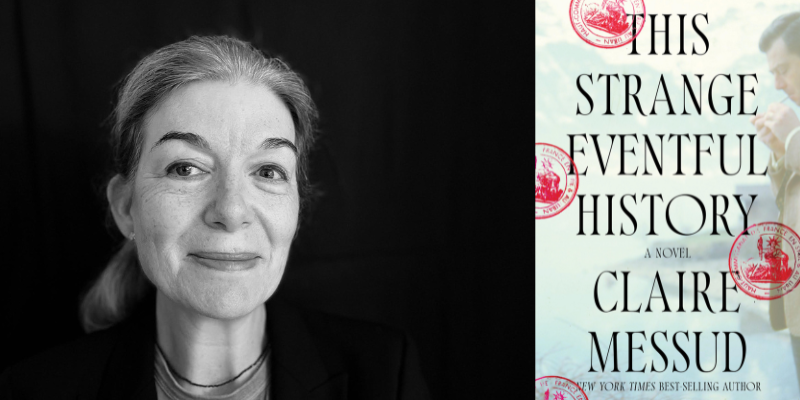

Claire Messud on Blurring Family History and Fiction

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

Author Claire Messud joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to talk about how the lines between autobiography and fiction blur, and the ways that families—real and imagined—hide their true histories. Messud’s new novel, This Strange Eventful History, draws on her own family’s complex past, including their connections to French colonialism in Algeria. Messud talks about using her grandfather’s 1,500-page handwritten memoir as source material, creating a story that spans the globe, how ordinary lives intersect with history, and including a character interested in questioning, editing, translating, and transforming family tales into a story for a different audience, as writers often do. She reads from the novel.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Anne Kniggendorf and Amanda Trout.

*

From the episode:

Whitney Terrell: You’ve said that your upcoming book, This Strange Eventful History, began with an entirely different 1500-page memoir written by your grandfather, which was shared throughout your family over time. Can you just talk about this document? What did it look like? Was it typewritten? Was it printed? What did the writing sound like? Was there dialogue? Was he a good writer?

Claire Messud: Those are good questions. He wrote it by hand. He had very neat handwriting and wrote on blank paper. I don’t know if he had a thing with lines underneath the page or if he just wrote in straight lines, but either way, it looks really sort of orderly. It’s in five big red loose leaf binders, and it includes photographs, letters, telegrams, restaurant receipts, tickets, their passports, all sorts of stuff.

He wrote it in the 1970s, and being super orderly, there’s the page number at the top, there’s also what year he’s writing about, and then there’s the date that he wrote each section. February 12, 1976, or whatever, is sort of written in the margins. He was covering 1928—when my grandparents got married—to 1946, just after the war. So, that’s the chunk of time that he wrote about.

He wrote in French, and I’m fluent, but I don’t use it so often, and so, people have asked me, “Oh, was that difficult to read?” No, it was completely easy, because that’s the French I know. There wasn’t really any time I had to look anything up. The rhythms of the sentences felt completely natural to me because that’s the French that I learned—being somebody who grew up learning French while not actually being in France.

So, was he a good writer? You know, he wanted to be a writer. That’s what he wanted to do when he was young. He wrote a book of short stories and a couple of novels. He didn’t try to publish them all, but he tried to publish one of the novels, and he didn’t have any success. He is a good writer, and there are lots of fantastic details about life that just bring their world alive to me.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: For someone to have not only written a document like that, but also to have maintained it, passed it down, and preserved it—I think that’s every writer’s dream. What an amazing thing that it has survived, that everyone can access it, and that it’s so organized.

WT: The thing is, family documents like that can also be nightmares. I have a few of those that I don’t want to read that are very boring. They aren’t the best. Sometimes I get terrorized by, “Oh my god, here’s another thing that someone has written that isn’t going to be actually interesting.” And then, sometimes they are.

CM: I think there’s also some that are interesting and not at the same time. There are passages, where he’s included a lot of stuff, including some documents. He was a naval attaché in Lebanon and Greece before the war, and he’s included some documents about that, which I have to say are a little bit turgid. Those are typewritten and stuck in there. I’ve kind of skimmed those.

The human stuff, he didn’t write it for publication or anything, he wrote it for us, and so, it’s sort of gossipy and full of detail. For example, my parents were really quite straight-laced, and my grandparents were super Catholic, and I assume straight-laced too. But, he described parties in Lebanon in the ’30s, and I believe there was a lot of wife swapping action—not them—but he described the parties, what they were like. It was some lively stuff.

VVG: When did you first read this? How does it influence your own writing?

CM: I had read little bits, but I had never read the whole thing until I had a leave from teaching in 2017. I spent a semester reading it from beginning to end and taking notes. My husband said, “Why are you taking such intense notes?” And I said, “Because I’m probably not going to read it all again.” I have my own little notebooks that are kind of the distillation of it. The thing is, I didn’t know quite what to do with it. Some people have said, “Why don’t you edit it and publish his work?” And, I think that would be difficult in that it’s way too long. There’s a lot of stuff that really is interesting to me but not for others, so it just became clear that wasn’t probably going to work. And then, I had an idea of writing four or five shorter novels, and my editor said, “No, Claire, you’re going to write one.”

VVG: For our listeners who have not read This Strange Eventful History, which is most of them, since it will be out on May 14, can you talk a little bit about the primary players in the Cassar family. Who is Gaston? Who are Lucienne, Francois, and Denise? What is unique about their stories?

CM: The Cassar family is a fictional family, but inspired in some ways by my own paternal relatives. They’re French colonials in North Africa. Gaston and Lucienne are married. She’s older than he is, but they’re basically the age of the 20th century, more or less. Their children, Francois and Denise are born in the early ’30s. So, the novel opens in 1940 and ends in 2010. There are seven different sections, each taking place at a particular moment in the seven decades, if that makes sense.

What’s unique about their story? Probably some things and probably nothing, too. There’s an epigraph, which I didn’t have when I started writing but that I really love, from Elias Canetti. It’s about how just living in the 20th century was enough to make a life meaningful and have texture and depth. In a way, you don’t have to be a politician or a hero or a celebrity to do something extraordinary. Just by living an ordinary life, you bump up against so much history—just by muddling along. That was one of the things I wanted to convey.

WT: One of my favorite things about Alice Munro’s fiction is the way she handles the character of young writers, often women, that sort of writer-to-be character. I don’t really care that much about whether Stephen Dedalus is or is not James Joyce, but I care about them because there’s something powerful in the writer-to-be character, in and of themselves. You have a character like this in the novel, Chloe, could you talk a little bit about her?

CM: Yeah, she comes in about halfway through the novel, which corresponds to where—in the trajectory of those decades—I would come in. So, she’s about my age. Just speaking about her as a character, she’s the character that’s in first person in the novel, and the others are close third. That was important to me. There’s a prologue that is in first person that is hers. In a way, it seems every story and every picture has a perspective. There are these different characters, and then there’s Chloe, in a slightly different relation to the reader and to the story. It isn’t her story. I would say she’s more a witness to it.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Mikayla Vo. Photograph of Claire Messud by Lucian Wood.

*

This Strange Eventful History • The Last Life • The Woman Upstairs • The Emperor’s Children • The Burning Girl • Kant’s Little Prussian Head and Other Reasons Why I Write • A Dream Life • The Hunters

Others:

France in Algeria • The Art of Losing by Alice Zeniter • Elias Canetti • Alice Munro • Ulysses by James Joyce • In an Antique Land by Amitav Ghosh • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 4, Episode 7, Claire Messud and Brendan O’Meara on Creative Nonfiction in an Era of ‘Fake News’

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.