It all began when my baby brother’s fever started getting worse.

I’d missed school for so many days it felt like I’d never even gone, that since I was born the only thing I’d ever done was take care of my baby brother. I stayed home while Mom went to work, and I gave him a spoonful of the pink medicine every hour and the clear medicine every four.

She had given me a clock with big numbers for my birthday.

The baby was light, he barely weighed a thing. It was like carrying wrinkled tissue paper in my arms. He didn’t giggle. He rarely opened his eyes.

One night, one of my mom’s friends punched a hole through the bathroom door, sick of hearing him cry.

“Shut it up,” he said to my mom.“Make that fucking creature shut up. If you weren’t such a whore, you wouldn’t have made such a monster.You should put it out of its misery.”

He cursed repeatedly and continued punching the door with his fist.

It was better he hit the bathroom door and not my baby brother. And not her. But he hit her some too.

We never saw that friend again, and it got harder to buy the pink medicine and the clear medicine, but she made it stretch with a little bit of boiled water.

She clenched her fists while waiting to take my baby brother’s temperature. Her fingers would be white after. And she made a little noise after shaking the thermometer in the air and looking at it under the lamp. A little noise with her tongue and teeth. When she didn’t make the noise it meant the baby was having a better day.

Some weekends she sent me to my grandparents’ house.

My grandpa Fernando would always take me to the cemetery to visit his dead mother, Rosita, first. Then we would go to La Palma to drink Coca-Cola with vanilla ice cream. A little girl with her grandpa. In a dress. With no brothers or sisters. An only child. Spoiled. It always flew by, and it was Monday before I knew it.

One afternoon while I was watching Woody Woodpecker, my baby brother started to cry. I didn’t go to him. It was time for the pink medicine, but I didn’t go. I wanted to watch Woody Woodpecker. The whole episode. For once in my life, a whole episode without having to look at the clock with the big numbers, without having to measure out the medicine with that big white plastic spoon, without having to fight to get him to swallow it, my clothes all sticky and smelly with the stuff, like always. I wanted to smell like a girl who watched Woody Woodpecker and did nothing else. I laughed, even at the parts that weren’t funny.

Loud, very loud, like Woody, to block out my brother’s cries.

After a while, the show ended and The Flintstones started. I watched that whole episode too.

When I went to check on him, the baby had stopped shrieking. I touched him. It was like putting my hand over a bright candle.

I called the neighbor, and the neighbor called my mom.

“Did you give him the pink medicine?” I nodded.

The doctor sent us some green medicine and suppositories.

I didn’t go to him. It was time for the pink medicine, but I didn’t go. I wanted to watch Woody Woodpecker.

My mom showed me how to give him the suppositories. I didn’t want to. My baby brother screamed like this little brown dog that was hit by a taxi once in front of our house and then left to die, with his guts on the pavement, but still alive. He screamed exactly like that.

Pink, clear, green, suppository.

The next day, we left my brother with my grandparents and went to Cristo del Consuelo Church. It was in the black neighborhood, the forbidden neighborhood. My mom and I were like two scoops of vanilla ice cream floating in Coca-Cola.

A large black woman told my mom to have faith. “Have faith, Doñita. Christ works miracles.”

Then she asked for money, spare change. Why didn’t she ask her Christ? If he could work miracles, he must be rolling in spare change, not like us, who sometimes had to walk places because we didn’t have enough to cover the bus fare.

The black lady sold my mom a little baby doll to hang from Christ’s brown robe. When we got inside the church, there were tons of those little dolls everywhere. And little hearts and little legs and little arms and little heads and other body parts I didn’t recognize. And photos and cards and bills and drawings. One of the cards read, Help lord Im only nine years od and I hav cancer.

“Mom?” I asked. “How is Christ going to know which of all these babies is my baby brother?”

“Because He is very smart.”

It smelled strange in there. Like old people, dust, like when I don’t wash my hair for days, like heat, like when the power goes out.

Before we left, my mom took out an empty bottle of Los Andes ketchup and filled it with water from a faucet.

“Good water,” she said. “Water from this sweet Christ, holy water.”

She gave me a sip, but it didn’t taste holy; it tasted like ketchup and a little rusty, and I thought to myself that water with ketchup—like what we put on our rice at the end of the month, when the bottle was running out—could not possibly work miracles. Holy water should taste like caramel, like a double hamburger. It shouldn’t taste like poor people. With that stupid taste in my mouth, I wanted to scream at the whole world that they were wrong, that the only miracle here was this woman getting change for selling little body parts and whole little bodies to stick on the skirt of a Christ who tasted like watery ketchup. My little brother stayed there, or rather, a little doll just as deformed as he was, surrounded by hundreds of other equally creepy little dolls and heads and arms and legs and hearts, like there had been some kind of explosion.

“He has to stay there,” my mom said, suddenly furious.

And I cried the whole way home because I realized that she didn’t know what she was doing either.

At home, my mom gave my baby brother a little bit of that water and poured some on his head. He opened his eyes and showed us his mouth, toothless. Finally, he smiled at us.

The following week, just like that, with that same smile, we put him inside a tiny white box that the neighborhood took up a collection to pay for.

I’m back at school now. Back in fourth grade again, where I’m huge and I don’t have any friends.

When they ask me if I have brothers or sisters, I think about that little baby hanging from the Cristo del Consuelo’s robes, and I say no.

They wouldn’t understand.

__________________________________

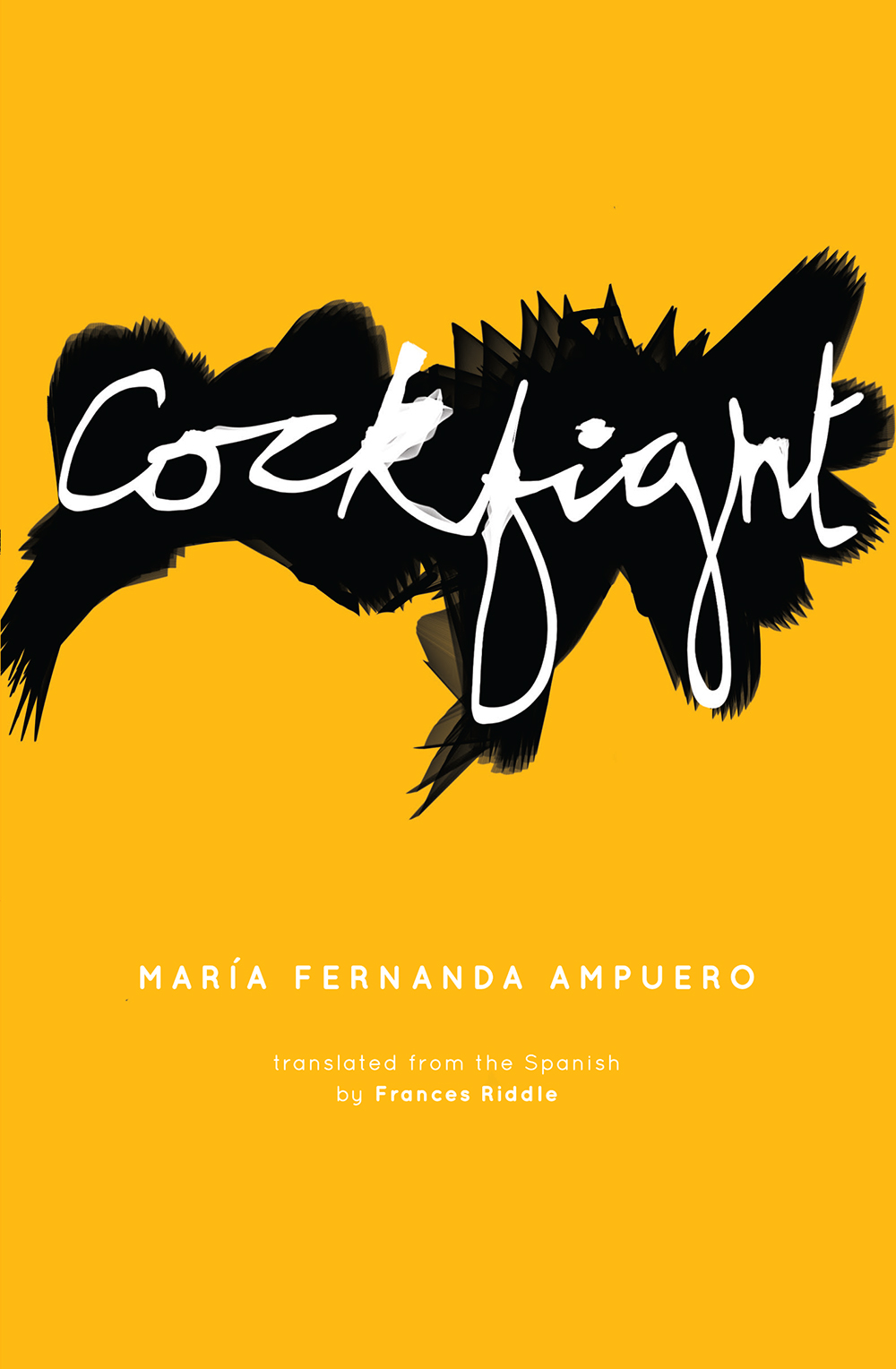

“Christ” is excerpted from Cockfight, a story collection by Maria Fernanda Ampuero, translated by Frances Riddle. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Feminist Press.