Chowder and Community: In Praise of Warm Meals and Warm Hearts

Tammy Armstrong on Finding Comfort and Inspiration in Fellowship and Food

Early in Moby-Dick, Ishmael and Queequeg row into the Nantucket harbor one mean December night, following some “crooked directions” to the Try Pots—a restaurant so famous for its chowder its yard is paved with broken clam shells.

“Clam or cod?” Mrs. Hussey, the proprietress, asks them.

Chilled and tired, Ishmael hesitates over her question. “Queequeg,” he asks, “do you think we can make out a supper for both of us on one clam?”

When he asks Mrs. Hussey for clarification, she hears two orders for clam chowder. Not soon after, Queequeg happily exclaims over his steaming bowl that it’s his “favorite fishing food” all in one place. Melville describes the dish’s salted pork, juicy clams, butter, softened hardtack, salt and pepper. The chapter is called “Chowder,” and it is, in essence, an ode to a modest dish that’s been a comfort food for centuries.

It’s a memory that’s always made me feel safe: the three of us over steaming bowls inside small circles of light, sheltered from the storm.

Here, in Atlantic Canada, chowder is as ubiquitous as it is in Melville’s New England. Every restaurant and home cook has a recipe that’s been passed down through generations or shared with new transplants. As with many comfort foods, it began as a dish of necessity, a dish that could turn bits of meagerness into something rich and filling. Even its name—though its origins are murky—probably derives from the French chaudière, meaning cooking pot or cauldron, as well as chaude, meaning warmth, suggesting it’s a dish with alchemical properties, capable of bringing people together while warding off the cold.

I grew up in New Brunswick, beside a tidal river that drew storms up from the Atlantic Ocean, often knocking out the power in its wake. Inclement weather warnings gave shape to many of our nights. Anticipating the worst, my mother would make fish chowder. When the power inevitably shorted, she’d heat up the pot on the woodstove while my sister and I did our homework by oil lamps at the kitchen table.

It’s a memory that’s always made me feel safe: the three of us over steaming bowls inside small circles of light, sheltered from the storm. I wonder how many stories have been told over the many years chowder’s been shared around a table on a rough night at sea, or in a tucked-away pub safe from the whims of nature: the rain beating against the windows, the snow drifting, high-shouldered and deep.

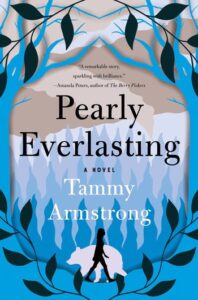

In my recent book, Pearly Everlasting, I thought about comfort food a lot. Food was an important element of daily life in Depression-era lumber camps because the men worked from sunrise to sunset. Food was something to look forward to at the end of another long, dangerous day. Pearly’s father is the camp cook. He’s one of the best—so good woodsmen tramp across the province, hoping to get hired wherever he’s cooking—because he cooks comfort food. While researching for Pearly Everlasting, I read old community cookbooks and interviews with camp cooks from the early 20th century, learning what they might make for hungry lumberjacks—cooking as though they were feeding a voracious giant—from a nonperishable pantry.

Sometimes in the spring, when the ice broke up and bears woke from their winter sleep, they made a chowder with stale bread, evaporated milk, and walleyes netted from the river’s fast-moving currents. A chowder. It was a dish the men looked forward to after so many months of baked beans and molasses. I often imagined Pearly and Bruno—a little girl and a runty black bear—the woodsmen and teamsters, surviving in that remote beauty, fifty miles from anywhere, eating something warm from a bowl inside lantern light. Short days. long nights. The deep hush of the woods. Rain falling and falling.

While I was going to university, I lived on the west coast of Canada. Out there, I made my mother’s chowder, or a variation of it, on rainy days, foggy days, and cold-snap days. I made it for friends suffering from heartbreak, recovering from illness and injury, slight veers in the universe, as well as for those celebrating big and small victories. I made it for international students homesick for their own countries, their own languages, their own comfort food. And I made it when I felt that very same way. Sometimes friends and roommates asked if I could make them a pot if they brought the wine.

Clam or cod? I said, soon filling up my kitchen, and every kitchen since, with savory and briny steam, sweating aromatics, cubbing russets, simmering them in a second-hand stockpot until they barely held their shape, maybe adding thyme from a little planter on the windowsill above the sink. Modest alchemy, slowing down time. All the while, friends and soon-to-be friends have sat around my kitchen sipping wine, telling stories, asking, is it raining again? Asking, is it chowd-er or chow-dah?

I wonder how many stories have been told over the many years chowder’s been shared around a table on a rough night at sea.

When we first moved to Nova Scotia—a very watery part of the world—my husband, a Colorado transplant, was always chilled. Being here means living with fog banks, going to sleep with the foghorn and waking up to its sad song. There’s a fluidity to the landscape here that’s different to other places I’ve lived. It sometimes feels like we’re inside slow traveling smoke or salt-wind spirits below the wheeling gulls. It can take a while to adjust, keep warm. So, I make chowder.

These days, I might make it with Cajun spice like I had in New Orleans one drizzly Easter weekend, while watching a ghost tour weave through the French Quarter; or with curry like they made on Grímsey Island, served with bread steamed in a hot spring; or with smoked haddock like the cullin skink I had in a Scottish pub while playing pool one stormy afternoon; or the cioppino I ordered in a checkered-tablecloth Italian spot outside Kansas City, on a late night filled with bright stars and ice like bottle glass. As we stepped out of the steamy restaurant later, we heard before we saw them: a long vee of Canada geese navigating across the night, heading home for early spring. This is just one way stories can travel.

A few russets, some leeks or onions, some milk or cream, some stock and fish—chowder mix, canned littlenecks missing their armor, haddock bartered for off the wharf, the give of a seared scallop, a toothsome poached halibut—and, of course, dinner rolls, oyster crackers, saltines. Friends will come, all the same. They’ll come for the stories. Look, we can see them through the little steamed-up windows: Ishmael and Queequeg ordering another bowl at the Try Pots, Pearly’s ragtag family—bone-sore and chilled—gathering as the moon hangs early above the snow-lit, lantern-lit cookhouse. Me in my kitchen with my mother’s recipe. Warmth and woodsmoke. An invitation. A gathering. The bowl scrapped again with a spoon.

__________________________________

Pearly Everlasting by Tammy Armstrong is available from Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Tammy Armstrong

Tammy Armstrong is the author of five books of critically acclaimed and award-winning poetry and two novels published in Canada, and one of her poems was finalist for a National Magazine Award. Her work has appeared in Canadian Geographic, Nimrod, Prairie Fire, and New England Review, among others, and Pearly Everlasting is her US debut novel. A former Fulbright scholar, Armstrong holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of British Columbia and a Ph.D. in Literature and Critical Animal Studies from the University of New Brunswick. She lives in a lobster fishing village on the south shore of Nova Scotia.