Chin-Sun Lee on Writing Landcape

"I know that wherever I am, when I stop to pay attention, some kind of story will emerge."

A version of this essay first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

For much of my life, I equated traveling to foreign cities with glamour, money, adventure, and independence. My father worked as a foreign consulate for the South Korean government, and before I was born, my family traveled to Indochina, Tokyo, Hong Kong, New York. My older siblings talked about visiting Buddhist temples, living in hotels, eating French cuisine, and I always felt cheated, because by the time I was four, my father had left the consulate to forge a new life for us in Los Angeles. Money was tight, and there was no more travel.

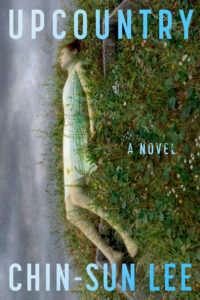

I made up for that lack as an adult when, long before I became a writer, I left L.A. for New York to work as a fashion designer. My jobs took me to Hong Kong, Paris, London, Florence, Milan—some cities, multiple times a year. I wore out luggage and pages of passports. But it was only when I stayed still in rural parts of America that I began to pay real attention to my surroundings, and let those observations seep into my writing. My debut novel, Upcountry, is a Northern Gothic set in a small hamlet in the Catskills, where a meandering creek, sprawling meadows, desolate woods, and inclement weather are as integral to the story as its three female protagonists. In fact, those elements of nature create the forcefield of tension, suspicion, and calamity that entangles them.

I doubt I could have written it if I hadn’t uprooted my life in 2014, when I left New York after living there for twenty years. I was burned out from work and already middle-aged. A few years prior, I’d started taking writing classes, then went on to get my MFA. But I had published very little, and residencies were out of the question because of my job. On a whim, I applied to the Playa Artist Residency, telling myself if I got in, I would quit my job, leave New York, and try to make a go of writing. I had some savings and I was free, without a partner or dependents. Playa accepted me.

Playa is situated on a remote desert basin in the Oregon Outback, against the backdrop of the Diablo Mountains. I had never been anywhere so vast and quiet, so underpopulated. I was there from February to April, and in that time, I saw wind and snow storms, hail-pebbled downpours, double rainbows, bright azure skies. In the late afternoon, I would stop whatever I was doing to look out my window and watch the horizon shift colors, minute by minute, in glorious darkening gradations.

Every day, I took a long walk. And I wrote.

I don’t recall what I’d intended to work on while at Playa, but once there, I knew I had to use the incredible landscape in a story. This was a new impulse. Stories usually came to me through a snippet of dialogue, an evocative image, or a persistent question. My powers of observation leaned toward interiority; meanwhile, I’d overlook what was right in front of me. It became a joke among my friends how often I’d notice some new store or restaurant in my neighborhood, only to be told, “Uh, that’s been there for two years.” I was not attuned to the physical world. This manifested in my writing as an acute attention to character (good), with an overemphasis on dialogue to do the heavy work (not good).

I’d never before been inspired by a setting—and at first, I was too perplexed by the sheer beauty of my surroundings (“How can I use this place? I don’t write pretty stories!”). But as I walked further up the mountain trails and saw the landmarks below me grow ever tinier, I became aware of how alone I was, how easily I could get lost, and how foolish it would be to underestimate nature. That awareness became the seed that led to my story, “The Ravine,” which I wrote and finished at Playa. Months later, I was in the Sonoran Desert and wrote “The Dry Season,” a story inspired by that blistering terrain and Valley Fever, an illness common to the area.

For the next two years, I lived out of one large suitcase, bopping from artist residencies to Airbnb rentals to the homes of family and friends; from Oregon to Arizona, New Mexico, California, Louisiana, Texas, and finally, upstate New York. I looked at each new place as a writing prompt—and by consciously utilizing my environment, something shifted in my writing. In Carmen Maria Machado’s memoir, In the Dream House, she writes: “Places are never just places in a piece of writing. If they are, the author has failed. Setting is not inert. It is activated by point of view.” This is absolutely true. But what I also began to realize in my wanderings is that setting could also impose action, directly putting characters in situations they might not be in otherwise: veering off the road in dense fog, losing power during a storm, collapsing in a heatwave. Gothic stories especially rely on setting and atmosphere, often in the form of an unsettling house or other property, alongside moody natural elements. And of course, the size and demographic of any given place impacts the way people behave.

I traveled through cities as well as small rural towns, but it was the latter I found more interesting. What intrigued me about small towns was the compression and familiarity that bred both contempt and tolerance. In a small community, there’s no place to hide; people know your business. There are grudges, grievances, gossip. But because you have to live with each other, there’s also an underlying civility, regardless of differing opinions or lifestyles. At least, that was my experience. This was also before the 2016 election, before the Trump administration, followed by the pandemic, ushered in a new era of political and cultural divisiveness.

In the Catskills, where I spent two consecutive summers, I encountered a mix of people from vastly different backgrounds, all able to coexist in relative harmony. For a mostly white community, there was a surprising sense of diversity in social classes, religious and political affiliations, and sexual preferences. There were ongoing social events: barn potlucks, barbeques, church fundraisers, weddings, yard sales, book clubs, not to mention dinner parties large and small. In big gatherings, there would be lawyers, financiers, artists, carpenters, farmers, soccer moms, and retirees, all rubbing elbows together. I’d never seen that happen in the city. Social circles there were much more circumscribed, and I doubt that, if the same group of people were airlifted onto the island of Manhattan, their interactions would have been the same.

I began to realize in my wanderings that setting could also impose action, directly putting characters in situations they might not be in otherwise: veering off the road in dense fog, losing power during a storm, collapsing in a heatwave.

I enjoyed the easy milieu I found in the country. Considering I was one of the few people of color (which was the case in all the rural towns I passed through), I didn’t feel discriminated against, or othered in an obvious way. It helped that I was introduced to everyone and vouched for by my hosts, longtime stalwarts of the community and parents of a dear friend, who generously let me stay in their guest house—a Colonial brick farmhouse built in 1832, just off a winding two-lane highway. The backyard was a huge grassy field dotted with irises, cosmos, hydrangeas, and echinacea; some distance away stood a pergola entwined with wild roses overlooking a creek. Who gets to live like this? I thought. I was so grateful just to be in one place for a whole summer, any housing would have been welcome. I felt so extraordinarily lucky and happy. There was nothing I needed to do but write every day.

I wrote from morning to late afternoon, then took a break to walk along the highway, when it was cooler. My usual route took me past an old cemetery, a goat farm, other houses, then a dense dark stretch of woods that, after a quarter mile, opened onto a wide rolling meadow, until the road curved back around to the main highway with a post office, mini-mart and gas station, the lone café, more houses, and back to the farmhouse. There was no TV and limited internet, so after dinner, I’d read or settle down to write again, late into the evening. Sometimes I could hear soft seventies rock drifting from a neighbor’s house far down the road…strains of Gordon Lightfoot and Gerry Rafferty keeping me company while I tapped on my keyboard. There’s something about faraway music on a quiet night that instantly evokes nostalgia, and I would feel a peacefulness, like a child safe at home after a long day outside.

Still, as bucolic and blissful as my daily routine was, I could see the potential for conflict.

I could envision a world where outsiders would be welcomed but expected to conform, where those who practiced different customs would be treated like interlopers. The world of my novel became the dark inversion of my idyllic reality, where congenial communal existence is ruptured by suspicion and fear. When I began writing Upcountry, it was a fictional premise that suited my novel’s themes; now, it seems to reflect an ugly truth about the world as a whole. I haven’t been back to the Catskills since 2018, and while I stay in touch with my hosts, it’s hard to know without being there how much the community that inspired me has changed. It seems naïve to believe it hasn’t.

I think back on those two summers with great wistfulness. I don’t know that I’ll ever have that kind of extended free time again. After that second summer, I re-entered reality. The bills pile up, the coffers must be replenished. I know my writing grew as much from having that immense luxury of time as it did from those rural landscapes and its inhabitants. But I also know if I’d taken the same amount of time and stayed in my small East Village apartment, I wouldn’t have produced as much work or been exposed to the range of human society that my wanderings enabled. The novelty of new experiences enlarges the mind’s eye. Not everyone gets to have that. I’m still oblivious at times to my surroundings. But I know that wherever I am, when I stop to pay attention, some kind of story will emerge.

____________________________________________

Upcountry by Chin-Sun Lee is available now via Unnamed Press.

Chin-Sun Lee

Chin-Sun Lee is the youngest child of North Korean exiles— both her parents having fled their native provinces for Seoul at the outset of the Korean War. After a long career in fashion design, she earned an MFA in Creative Writing at The New School in New York. Her work has appeared in Joyland, Your Impossible Voice, The Doctor T.J. Eckleburg Review, and The Believer Logger, among other publications. She currently lives in New Orleans, working on her second novel. Upcountry is her debut.