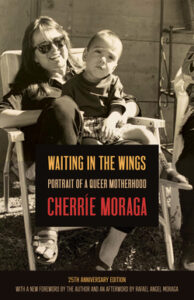

Cherríe Moraga on Writing About Queer Motherhood

The Celebrated Author and Activist Revisits Her Own Memoir

As a cultivated writing praxis, creative nonfiction allows for a broader panorama of experience than a genre restricted to the empirical.

It is one which permits dreams to presage and queer bodies to serve as repositories of memory. With the best of intentions, I believe Waiting in the Wings, my memoir of motherhood being republished this year, does just that, perhaps even more so from the historical perspective of twenty-five years since its original publication in 1997.

Wings offers a queer view of motherhood and mothering from an era preceding national legalization of same sex marriage and gay adoption. Discussions of nonbinary gender identification and queer sexuality along the more generous gender continuum we know today were not the LGBT lingua franca of the early 90s, nor was the acronym widely employed, or the “T” in the acronym. At that time, in my neighborhood in San Francisco TransLatina public visibility was largely restricted to the drag shows at Esta Noche on Valencia and 16th. [1]

Looking back has given me pause.

Although I am grateful for, and beholden to, the activists whose struggles secured us queers our twenty-first-century rights, I ask myself if legalization and all the language we accumulated along the road to achieving it might not have also unwittingly convinced us we were free. For many queer people, it might as well be the 1950s and 1960s of my childhood, with liberation still “waiting in the wings.” For them, and for us, who imagine ourselves thoroughly “enlightened” about our queerness, I believe Wings may offer a different road to wholeness. It excavates buried questions, exposes contradictions hardly understood in the body. In retrospect, the writing seems marked by the yet unseen; by the failed to mention but known by heart. Inscribed by a Chicana/Xicana/Xicanx queer mother, I believe the work speaks to a bit of what remains missing in “America’s” national consciousness.

Waiting in the Wings began as journal entries; a record of my forty-year-old lesbian genderqueer [2] self in the act of becoming pregnant and giving birth. But within months of that initial journaling, the writing became something unanticipated, something I had only witnessed in dreams, anxiously recorded on the page. It became a meditation on death and dying. I had seen death coming down the road, first in the shrinking fragility of the old ones in my familia; not yet of my mother’s generation, but that of her mother—a ninety-six-year-old twig of tenacity splintering into the embrace de la muerte. From early childhood, I still hold the distant memory of the other grandma, the white one. After a stroke, her flaccid skin melted onto her skeletal frame as surreal to my young eyes as a Dalí painting.

Fast forward to decades later when AIDS entered our queer world, turning some of the most brown and beautiful jotos [3]into old men overnight. The women followed soon after. Margarita and I are dancing in an Acapulco Bar one summer and by the next, she disappears into the obscurity of SIDA. This was the world in which I would give birth to my son, just shy of my twenty-eighth week of pregnancy on July 3, 1993.

Suddenly the what happened? of the journal writing was eclipsed by what will become of us? I very quickly learned what it meant to carry susto in the body; to no longer trust the universe to be on one’s side. To pray for the best and ready yourself for the worst. I also learned the daily gift of survival, its necessary faith, and the willingness to accept loss.

In my 2010 Xicana Codex of Changing Consciousness, I called the perilous birth of my son and the slow Alzheimer’s dying of my mother in 2005 “bookends.” The former would prepare me for the latter. There were others in between and after: Marsha, Ingrid, Mahsa (Will I ever grow tired of writing their names?); this, the litany of loss that profoundly changed my worldview. All would require of me a different kind of writer. But, without exception, confronting death in the creative locus of giving birth to Rafael Angel welded a warriorship in me to meet all the rest that followed.

The experience described in these pages matters in the repertoire of queer literatures. Because the mandate of art, and I would like to believe queer art especially, is to account for unspoken truths in which the equations do not always add up. Like so many others, my queerness has never added up exactly into neat categories of sex, gender, and sexuality; and yet it has shaped who I am every step of the way, including throughout nearly three decades of mothering.

My female sex was determined at birth and I rebelled against its socialization to the degree possible as an utterly tomboy child, followed by a suffering closeted trans-terrified and woman-lusting adolescence, to eventually emerge into at a butch-identified adult lesbian. Theis is old and common language, but true to my experience, coming of age in the late 1960s.

What I hadn’t realized was the degree to which my self-perception as a butch lesbian would be so profoundly impacted by the somatic act of motherhood: the hormonal changes, the breastfeeding, the adrenaline fight for my son’s survival. I have never been able to forget—nor would I want to forget—what was learned there.

Birthing confirmed for me on an utterly corporeal level that female sex in no way requires one to “present” as a woman in the socialized sense of the word. [4] It viscerally reminded me that “female” is simply biological and that I had a right to that biology in my own gendered version of it, should I so choose. For me, my anatomical sex wasn’t wrong. The world is wrong about any gendered imposition on that sex, something intersex people have long publicly asserted.

It is also a feminist and queer right to insist that womanhood in whatever way one understands it (including as transwomen) matters politically in a misogynist world. It remains an oppressed class among humans as we walk in our gendered and (for women of color) racially marked bodies every day of our lives. Oh, I know it is all more complicated than this. [5] But I got a taste of what it is like to experience the female animal I am and it was something I took hold of toward the whole of me. Perhaps this is what transfolk have been trying to teach us all along-their rightful entitlement, with the aid of hormones (and surgery for some), to get the biological sex “right” in order to experience that same wholeness of being.

In the larger landscape of this story, it is 1993 and Rafaelito is already a presence in my womb. Together, we attend our first Medicine Ceremony. The Roadman, William Baker, sits behind the sacred fire, officiating. It is a “manly” affair; and I have recently learned of my baby’s male sex. I speak to my son, a knowing spirit growing inside me. We begin a lifelong dialogue—mother to son.

Last summer, twenty-eight years later, Rafa would return, now a grown man, to that same Roadman’s ceremonial fireplace; this time guided by the hand of a faithful stepbrother. Days later, on Roadman Baker’s way home from that Ceremony, he, and his twelve-year-old grandson would be killed in a car crash.

In the twenty-five years since the publication of Waiting in the Wings, my son’s life and my own continue to weave together threads of connections—of beginnings and endings—which direct us to the next step in our lives.

What does this tragic loss mean? We ask.

Where do we go from here, this time?

Two and half decades later, the subtitle of this work—Portrait of a Queer Motherhood—resonates for me more deeply than ever. It is, indeed, a very “queer” tale; but today, knowing my son as a young man, I understand more fully that this work is less a story about him and much more about what I learned mothering his endangered birth and insistence on life. He has his own story to tell and live—with a view toward a future I will not witness, as he did not bear witness to my past.

Such is life and death and life again.

*

[1] Also, in the same neighborhood in the early nineties, CURAS and El Proyecto Contra SIDA por Vida, grew out of the AIDS pandemic serving the Latinx queer communities, significantly transwomen.

[2] That is, “Masculine of center.” Neither was in our queer vocabulary at that time.

[3] Latino queer men.

[4] There was little “gender dysphoria” in the experience. Perhaps this speaks to my place on the gender spectrum.

[5] Discussions on the relationship between biological sex and gender continue to evolve, as does my understanding.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Waiting in the Wings: Portrait of a Queer Motherhood by Cherríe Moraga, available via Haymarket Books.