Chasing a Waking Life: On the Pains of Being an Insomniac

Aminatta Forna Moves Through a Cultural and Personal History of Sleeplessness

For 15 years I could not sleep. I would wake up in bed in our home in London at four o’clock in the morning, or three-thirty or four-thirty. Without looking at the clock I came to be able to estimate the hour with some degree of precision. In the winter months, when it was dark until at least seven, I’d lie for a while hoping I was wrong. In the spring I would play with the thought that the sky was merely overcast, clouds obscuring the dawn. None of these attempts to fool myself made any difference, for sleep: silvery, slip-skinned sleep, was already gone from my grasp.

Sleep left me in the year 2001. I realise now that my sleeplessness coincided with my decision to become a writer. My first book, the one I was working on then, was a memoir. It was tough—the excavation of facts and memories, the confrontation with both truth and lies. It consumed me. I began to wake up in the night thinking about what I knew, re-examining the past in the face of new facts, considering how I might discover what I still needed to know. I couldn’t stop thinking. The next day I’d be edgy and aching but my mind never stopped.

When it seemed that my sleeplessness was not a passing phase, I began to practice what I discovered was called “good sleep hygiene.” That is, I stopped drinking coffee after midday. I drank valerian tea before bed. Alcohol, nicotine, chocolate, TV—these are all stimulants. I stopped drinking wine after dinner. I did it, even though part of me is made skeptical by the way all good advice seems to start: by telling us to stop doing things we enjoy.

As the weeks wore on, I visited my doctor, who prescribed Zopiclone, a sleeping pill designed for the short-term treatment of insomnia. Sometimes the pill worked, or so it seemed, and sometimes it appeared to make no difference. The trouble was I didn’t like the way I was left feeling the next day: as if the cells of my brain had drifted infinitesimally apart, whirring and whirring but not quite engaging.

For most insomniacs, getting to sleep is the hard part. This is called sleep-onset insomnia. Peretz Lavie, an Israeli sleep scientist, studied the sleep patterns of civilians living in conflict zones during the Gulf War. During those nights people were too anxious about dropping bombs to sleep; once the bombs stopped they slept again. The causes of sleeplessness are varied and may result from external factors—noise and light pollution, caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, bombs dropping. Scientists don’t consider this kind of sleeplessness to be the same as insomnia.

Lavie thought that (in the absence of any medical or external causes) sleep onset insomnia might become a learned behavior. In an experiment at the University of California, researchers applied an electrical stimulus to a cat’s hypothalamus: the area at the base of the brain which controls sleep. The cat instantly fell asleep. The researchers then sounded a note just before they delivered the shock. After a while the cat only had to hear the note played and it would nod off. Pavlov’s cat. So it is with humans. That is to say, for most people all the bedtime rituals are a preparation for sleep.

Lavie noted that for the insomniac the reverse occurs: the bathing and brushing of teeth and hair, the settling onto a pillow, these only bring on a sense of dread. By the time they are in bed their blood pressure and heart rates have peaked. Caught in a loop, the insomniac’s inability to sleep becomes chronic. To break the pattern, Lavie gives the opposite advice to the sleep hygiene disciples. Drop all of those careful routines and fall asleep fully clothed in front of a television. I, however, self-diagnosed as suffering not from sleep onset insomnia (the condition Lavie describes) but from sleep maintenance insomnia. I could fall asleep; I just couldn’t stay asleep.

The time before I can remember is when I slept best. As a child I slept in the back of cars, I slept on airplanes, I slept in a tangle of sheets, I slept in the arms of one parent while another remade the bed, I slept while they set me back down and turned out the light. On trips to my grandparents’ house I slept in the big bed with my grandmother. I slept while she did not (she complained I kicked her in the night). As a child I slept. My own son, who is ten at the time of writing, sleeps. Thoughts of school don’t keep him awake at night and nor do they cause him to wake with a start in the morning. What wakes him early on weekends are thoughts of play and the early-morning cartoons. He sleeps in during the week and, frustratingly for his parents, leaps up at dawn on the weekend.

A friend, who is also a psychologist, sent me a cartoon he thought I might appreciate. It went something like this:

Bladder wakes up in the night. “I need the bathroom,” she hisses.

“Can’t you wait?” asks Legs.

“I really need to go,” pleads Bladder.

“Do you hear that?” Legs says to Eyes.

“Okay,” replies Eyes. “But nobody wake Brain.”

None of these attempts to fool myself made any difference, for sleep: silvery, slip-skinned sleep, was already gone from my grasp.

So the sleeper heads to the loo, but somewhere on the way back Legs stumbles and bumps into a piece of furniture and with that wakes up Brain.

“What?” cries Brain, “It’s the middle of the night and we’re up. I’m so excited! I just want to think about all the stuff we have to do today. Let’s stare at the ceiling until they happen.”

“I think therefore I am,” says Descartes. What then does it mean to cease to think, rationally at least, for seven or eight hours each day? Do we cease to “be”? Jean-Luc Nancy, another French philosopher, is of the opinion that when we sleep we become something else, another kind of “being.” In sleep we become another self, the dark self, in whom Nancy believes the soul and the mind are in harmony.

In his treatise, The Fall of Sleep, Nancy contemplates the descriptive language of sleep, in which we are “dead” to the world, the significance of the word “fall” and the faith required of the act of falling. For Nancy, the insomniac is plagued by fear:

He is afraid of letting go even of his troubles and his cares. He wears out his night in stirring them, in ruminating over them like thoughts bogged down in tautology, becoming viscous, creeping, insidious, and venomous. But what he fears above all else is not that the difficulties or dangers that these thoughts display threaten to arise as so many failures and defeats on the following day, what he really fears more than these fears themselves is leaving them far behind him and entering the night.

Psychological distress is the principal cause of insomnia, combined with a hair-trigger sympathetic nervous system, our so-called “flight or fight” mechanism. As I have said, I was writing a book that obliged me to revisit highly charged and sometimes dangerous episodes in my early years; also I have always been what you might call a “light sleeper.”

As these things go, I have a sensitive sympathetic nervous system. I’m the person who starts at sudden sounds and jumps if someone comes up unexpectedly behind me. In insomniacs the vigilance centers of the brain producing those impulses stay awake, while those of good sleepers close gently down.

Also, I am a lucid dreamer, which means that sometimes when I dream, I’m aware of the fact that I’m dreaming and can make conscious decisions within the dream. Only ten percent of people are lucid dreamers. Once I dreamt I was about to skydive and that I felt afraid and unprepared. Then I thought, You know this is only a dream and you’ll probably never get to do this in real life. And so I leapt through the open hatch of the plane.

I have nightmares and will call to my husband to wake me up, and he often has. He says I’m not calling out but making muffled sounds of distress. Relief comes with the feel of his hand on my shoulder. Trying to escape a nightmare on my own is like being trapped in an underground tunnel. I have found no mention of an established link between insomnia and lucid dreaming, which itself was only proven to exist by researchers in 2013, but for me it stands to reason that someone whose brain is still partly awake might be both an insomniac and a lucid dreamer.

Most studies you might read put the figure of insomniacs in industrial and post-industrial countries at about a third of the population, and on the whole, these are not writers with a heightened response mechanism plus a history of childhood adversity. A third of people! After I discovered that figure I would keep coming back to it. Is there a tipping point at which a condition ceases to be considered abnormal? If half of us couldn’t sleep seven straight hours, who would be the odd ones out? The ones who could or the ones who couldn’t? When does a dis-order become the order?

My big problem was boredom: the tedium of being forced to pad around a cold, silent house where others were sleeping, trying not to step on an errant floorboard. There was no turning the sleepless hours into productive ones. I didn’t feel like writing, at least not the book I was working on back then, but not any book really. It was frustrating. I wrote emails and found them to be filled with the exasperation I was then feeling, and so I stopped or I stopped sending them until I had reread them in a less strained mood.

I had then a dog, a black lurcher called Mab, after Queen Mab. Perhaps in naming her I already recognized the fickle relationship I had with sleep. I had once known Mercutio’s monologue from Romeo and Juliet by heart:

She is the fairies’ midwife, and she comes

In shape no bigger than an agate stone

On the forefinger of an alderman,

Drawn with a team of little atomies

Over men’s noses as they lie asleep.

Shakespeare’s Mab bestows sweet dreams upon lovers and of curtsies upon courtiers, but when angered, Mab turns into a hag, whipping up nightmares and conjuring plagues of blisters upon the sleeping, frightening the horses and generally making things go bump in the night.

Sometimes she driveth o’er a soldier’s neck,

And then dreams he of cutting foreign throats,

Of breaches, ambuscadoes, Spanish blades,

Of healths five fathom deep; and then anon

Drums in his ear, at which he starts and wakes.

One night, I rose from my bed, urged my own Mab from her basket and drove through streets, in which not even the dustmen or sweeps moved, to Kensington Gardens. There were the others, among the outlines of the trees, the spectral figures of my fellow insomniacs. On different nights, driving through the silent streets, I became familiar with the solitary light in an otherwise dark row of terraced houses. The insomniac’s beacon.

As a writer needs a room of her own, so does an insomniac. Once I couldn’t sleep without my husband, then I couldn’t sleep with him. During the worst of my insomnia he would go to sleep in the spare room. He is someone who can sleep anywhere and for however long he has. When we boards a plane he is already poised for sleep, sometimes he doesn’t even bother bringing a book on board, but tilts his head back and closes his eyes. As sleep grows more elusive, so the tools to entice it become more elaborate: the goose-down pillows, the sleeping pills, blackout curtains, ear plugs, eye masks. At some point I have tried them all, and at some point they have all failed me.

When does a dis-order become the order?

Gradually I grew to know the patterns of my insomnia. I’d wake up at 4 am, usually following a dream. I would start to ruminate. A writer always has something on her mind. I’d lie awake and think about the direction of my research, the line of my plot, the qualities of my characters, whether I had fallen into the trap of cliché. My brain would try out sentences, and then, if I arrived at a pleasing phrase, knowing I would forget it in the morning, I’d get up and write it down. I began to keep a notepad at my bedside. Franz Kafka, Charles Dickens, Sylvia Plath, William Wordsworth, the Bronte sisters, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Walt Whitman were all reportedly insomniacs. Some of those writers said insomnia was vital to their process, but I cannot say that I ever felt it was vital to mine. It came to be part of it though, and in time I knew there was little to do but accept it.

In those wakeful hours I would check the clock. I’d look when I woke up, hoping I had managed to stay asleep until seven or six. I’d even take five o’clock, for the difference between five and four is that one belongs to morning and the other tonight. I’d check the clock every 20 minutes thereafter to see how much time I had left before the alarm sounded.

Insomniacs, though, are not the only people in the habit of counting up the number of hours we have slept. Everyone does it. And everywhere I have ever been, people will ask you how you have slept. How did you sleep? Tu as bien dormi? Sleep has always been a source of concern. And increasingly with reason, for today those of us who live in post-industrial nations sleep on average seven hours a night, nearly an hour less than 30 years ago and two hours less than 80 years ago.

Reading Jean Verdon’s La Nuit au Moyen Age brought me to the discovery that the way we sleep now is not the way we always slept. During the long nights of the Middle Ages, sleeping habits were quite different and different again depending on whether you lived in the countryside or the city. For farmers, the working day ceased when the light went. Night began with the onset of darkness. Darkness meant danger, nowhere more so than the city.

“Fear of night, fear in the night,” writes Verdon. “Fear of darkness amounts to a dread justified by nothing but the absence of visual perception. Man cannot live unharmed in darkness. He needs to see to act.” In European towns and cities night was announced with the sounding of the curfew bell. The city gates were closed, the drawbridge pulled up, people ceased work, went inside and bolted their doors until another bell announced the start of day.

Every house has a night-time ritual. In ours, in London at that time, we’d let the dog out and watch her disappear briefly into the darkness at the end of our long and narrow London garden. Before retiring we’d bolt the back door, top and bottom, turn the heavy iron key of the mortise lock, which for some reason had been fitted upside down by the Victorian locksmith, and finally, slide the barrel bolt. Every night the same performance was repeated at the front of house, and in winter we’d draw a heavy velvet curtain across the door against the draughts. Then we’d retreat upstairs and hunker down for the night.

Once we were robbed while we slept. The police told us there was a “sneak thief” operating in the neighborhood and we were not his first victims. He came in through the dog flap, which I had left open because by then Mab was aging and infirm and needed use of the garden. I knew a human could fit through the flap, because I had done it myself when I taught her how to use the door. I explained all this to the police.

As a writer needs a room of her own, so does an insomniac.

Also, how another policeman had once told me a story of how they had caught a burglar and, in his pocket, found a map. It showed an aerial shot of houses in the neighborhood, some of which were marked with an X. When the police conducted visits, they discovered that those were the houses where the people owned a dog. The map was traded between thieves.

“This is pit-bull territory,” I said to the policeman. “Who would dare to stick their head into a dog flap that size?” But the police explained the thief had been watching our house. He knew that our dog was old and ill. He’d taken only a camera and a bit of cash, not much for the risk, you’d think. But for a sneak thief, it’s all about the thrill. To get into your bedroom and watch you while you sleep. I’d had a bad cold and I’d taken a nighttime cold remedy to help me sleep. Simon had gone to the guest bedroom. Just that once, I wasn’t awake.

Nights in the Middle Ages were long and so divided into what was called the First Sleep and the Second Sleep, with a period of wakefulness in-between during which people might perform chores, care for children, bake bread, or find a quiet place to make love—for communal sleeping was the norm and moments of privacy had to be sought out. In 1992, Thomas Wehr, an American psychiatrist, published the findings of a recent experiment in the Journal of Sleep Research.

Wehr had persuaded eight student volunteers to spend 12 hours a night alone and in complete darkness. He found the volunteers soon settled into a pattern of sleeping for a total of nine hours out of the 12, with a period of wakefulness in-between. During the hours of wakefulness, they neither fretted nor fidgeted, but lay peacefully, in a semi-meditative state. In France this time was once called the dorveille, in England “the watch.” Wehr’s tests showed the volunteers had elevated levels of melatonin and prolactin, both of which promote calmness and contentment.

During the day they reported feeling better rested and more awake, and by the standards of the sleepiness scale researchers used to check their wakefulness, they were indeed more alert. Writing about his findings, Wehr speculated whether “the watch” had once long ago provided a “channel of communication between dreams and waking life which has gradually been closed off as humans have compressed and consolidated their sleep.”

That makes sense to me. In Sierra Leone, among the Temne, we have a name for this place. We call it “Rothoron,” the liminal space between sleep and wakefulness. In the village of my ancestors life hasn’t changed that much over the centuries. People live by rice farming, only the school building, where we have installed solar panels, has electric light. At night, on the verandah of each house, the yellow flame of an oil lamp burns. Otherwise the nights are so black, you cannot see your hand in front of your face.

People retire early. Rothoron is the place (for it is considered a place and not a time) where the spirits and the living meet. In the morning the villagers greet each other much the way others around the world do, ‘Ng dirai? Literally, Have you slept? But meaning, Did you sleep well? Was the bed comfortable? I hope you were not woken by the cockerel’s cry? The Temne mean all of that, and perhaps, Did you meet anyone in Rothoron?

In Croatia, in Smiljan, a village near Gospić, there is a memorial center and a small museum marking the place where Nikola Tesla, the inventor of electricity, was born in 1856. In London, when I couldn’t sleep and was out walking with Mab, I would sometimes go to the small park at the top of Telegraph Hill where we lived, which gave a view of the city skyline, the lights of which blanched the night sky above and irradiated the waters of the Thames below. It is strange but true that you don’t have to go far beyond the boundaries of Gospić to find rural folk living much as they did during Tesla’s time, without power to their homes and whose fresh water comes from a well. Nevertheless, it was Tesla’s invention that dramatically changed the human relationship to sleep.

The first electrical systems were installed into factories and enabled production to continue after the hours of darkness. Workers were obliged to schedule their sleep more efficiently in order to meet those demands, such that now we sleep in a single, consistent block just once in 24 hours. We became what scientists term monophasic sleepers.

In the late 20th and 21st centuries emerged first, 24-hour economies and soon, a 24-hour global economy. This has meant that shift workers, that is, people who work in service industries, currency traders, computer tech workers who update office systems at times when they are not in use and the people who clean those same offices, truckers, flight attendants, medics, train drivers—all these people now don’t get even seven straight hours but suffer irregular and disrupted sleep times.

As a result of these developments, research into sleep and the effects of sleep deprivation has increased exponentially in the last three decades. The first locus of interest was the military. Anthropologist Eyal Ben-Ari researched practices relating to sleep within the armies of industrialized nations and the way technology has been used to monitor the sleep of individual soldiers with the aim of maximizing their fighting capabilities.

In the mid 1990s, the US Army Medical Research and Development Command developed an elaborate “Sleep Management System” using information gathered in the Gulf Wars. The system includes a wrist-worn “Personnel Status Monitor,” which records the amount of sleep a soldier has had, combined with “pharmacological agents to assist in the sleep/wake cycle”—in layman’s terms, “uppers” and “downers.”

The wrist-worn microprocessor is designed for efficiency—the data is sent straight back to central command—and to bypass the fallibility of self-reporting. It works by recording arm movements, in much the same way as my much later, mass-market FitBit does. Central command analyses each soldier’s data to predict outcomes in performance for both individuals and units. Soldiers are issued with two pills, one to induce sleep and the other to return to a state of full alertness. Ben-Ari calls these schemes “‘Cyborgs’—cybernetic mechanisms—those hybrid machines and organisms that fuse the organic and the technical.”

When I haven’t slept for days, I wake faintly awash with nausea.

When I haven’t slept for days, I wake faintly awash with nausea. Life becomes like a bad dream, one of those in which I try to run but my legs won’t move. My thoughts congeal. There seems to be a time delay on my responses. I know I will achieve little that day, so I attend to paperwork and taxes. I want to sleep but I can’t. I become snappish. I wish everyone would just shut up. As more nights pass, I reach for the chemical cosh. I am fortunate in that my job does not require me, except on certain occasions, to make split-second judgments or to, say, hold a scalpel very still. In one of my novels, I wrote about a surgeon whose insomnia was beginning to affect his ability to do his job.

Lack of sleep causes lapses in attention, irritability, clumsiness. After a while, affected people start acting like drunks. When I first wrote about my insomnia, I talked to Martin Moore-Ede who had acted as an expert witness for an airline pilot pulled over for drunk driving and ran a company called Circadian Technologies. He still does, only now CIRCADIAN 24/7 Workforce Solutions has offices in America, Europe, Asia and Australia and advises over half of the Fortune 500 companies. Moore-Ede first became interested in sleeplessness while working 36-hour shifts as a trainee surgeon in the mid-80s, left surgery to study physiology and later helped found a research laboratory for Circadian Physiology at Harvard.

“This is a hundred-year-old phenomenon,” he told me. “We have basically created problems that did not exist back then.”

In the 19th century, for the rising middle classes, sleeping became a private rather than communal affair. Thus, today, we train children to sleep alone. We teach them to “self soothe,” which is another way of saying “cry it out,” with a blankie or teddy to replace the warm body of a parent or a sibling. Our schedules demand it and one day so will theirs.

Seis. Six. From the Latin sexta. Siesta. The arrival of darkness, the disappearance and reappearance of light, are only part of what determines a people’s sleep patterns. Climate and geography play a role too. In countries where the temperature during the middle part of the day is too hot for manual work, people often retire to rest for an hour or so. These are the biphasic sleepers. Though the siesta is associated with the Southern European and Latin cultures, the tradition of a daytime rest exists across the globe.

In China, Chairman Mao reportedly suffered from a 28-hour circadian rhythm as well as other sleep problems (according to Li Zhisui, Mao’s biographer and personal physician from 1955 until Mao’s death in 1976), which is widely believed to be the reason why the traditional midday nap was written into China’s 1954 Constitution and has survived as Article 43 of the current 1982 Constitution of the People’s Republic of China: “Working people in the People’s Republic of China have the right to rest.”

On June 1, 1944, in Mexico, the government, to widespread surprise, abolished the siesta for office workers. In the interests of the war effort, they said. According to contemporary reports in Time magazine and the New York Times, the journeying back and forth from home to office to home to office was putting too much strain on public transport, wearing out the buses. In addition, the long working day used up too much electricity. Before the change, the official office hours for government workers were ten o’clock until one o’clock and then four o’clock until nine at night. Imagine that.

In Spain, the siesta is said to be on the wane, as employers give in to the demands of a global marketplace, though in smaller towns it seems to hold still, for on my visits there I have always found it impossible to find a bank or a shop open at three in the afternoon. In the cities, even if people don’t go home to sleep, lunch is taken at a leisurely pace at two in the afternoon, people work later and dinner is eaten at ten o’clock at night.

An American I knew in Spain complained that during business dinners important matters were often not discussed until after midnight. The Spanish are holding out, at a cost, but they are holding out. The Chinese midday nap, for a period under threat from the same quarters, has apparently enjoyed a resurgence but for different reasons. Since the free-market reforms of 1979, China has become the world’s largest economy. The long hours of production make it more profitable for employers to allow workers short naps at their desks, in order to sustain even longer hours.

In our world, time is money.

The sight of a person whom I don’t know sleeping bothers me. In the absence of the veil of the constructed self we wear when we are awake, it feels to me like seeing a stranger naked. Sleeping with somebody is an act of intimacy, even more than the sexual act, for lust is a very forgiving mistress. Sleeping together requires trust; each becomes the holder of the other’s secrets: the nighttime cries or sleepy mutterings, the snores or farts. The public sleeper is at his or her most vulnerable, but doesn’t seem to care. There they lie: slack-jawed, mouth agape.

And yet in many countries, people sleep in public all the time: the taxi driver in Morocco, awaiting a fare, tilts the driver seat back as far as it will go; the Indian rickshaw driver sprawls on the back seat, one arm flung across his eyes; the Brazilian office worker on a park bench. Sometimes anywhere will do. In Sierra Leone, I once sat opposite a slumbering legal clerk for 20 minutes after which he raised his head, saw me there and said: “How can I help you?” Looking back, perhaps it was his lunch break and he decided to have a nap. And why not? At the time I was outraged. In our world, time is money. And here was a man literally asleep on the job.

Not many women sleep in public though, and the reason for that doesn’t require explanation. I, apparently, cannot even sleep in private. A boyfriend once told me he’d never seen me asleep. That whenever he rolled over in the morning, I’d be lying next to him with my eyes open.

Back when I first wrote about sleep, I said it was no coincidence that the polyphasic societies are often the poorest. Swiss sleep researcher Alexander Borbély observed the progression in humans from the polyphasic infant, through the napping or biphasic child to the monophasic adult. Sleep researchers saw this progression mirrored in societies as they moved from pre-industrial to industrialized. The thinking then was that the anarchic polyphasic sleeper would soon enough receive their wake-up call.

But factories have been replaced by call centers, and the technological leap which has allowed some countries to skip the established route to industrialization may in fact place them at an advantage in the future when it will be the people who are able to sleep anytime, anywhere—the flexible sleepers—who are most able to take advantage of the requirements of global networking. Today organizations from Google to NASA provide sleep pods and spaces with dim lights, eye masks, and mood music so their employees can catch a pick-me-up power nap.

Sleep is a political issue. When and how we sleep is in the hands of authorities higher than ourselves. In Paris, in the 18th century, the masses demonstrated their anger against authority by smashing street lanterns. For them, artificial light was a symbol, not of civilization but of oppression. For a while I refused to give way to insomnia. I tried to accept my sleep patterns rather than fight it, resolving to work around it. Then halfway through a book tour, fractious with insomnia and jet lag, I telephoned my publisher from Chicago O’Hare Airport and begged to be allowed to go home.

The next day I walked into the nearest pharmacy and bought an over-the-counter remedy, which you couldn’t then buy in the UK, and which worked. I took the pills every night for the next nine years. Every time I went to the States, I bought new supplies and hoarded them. Then, four years ago I stopped taking them. I can’t recall any specific turning point; I was just tired of it all. Also, I worried I might be addicted to the pills, which carried a warning on the label that I had chosen to ignore, much like everyone else I know who takes sleeping pills.

One thing is true, the more I think about sleep, the less I sleep.

At first I suffered “rebound insomnia” (what happens when you stop taking sleeping pills—the insomnia gets worse for a while). It is why so many people end up with dependency problems. I weathered it for weeks until my sleeping stabilized, or at least, until it fell into a pattern all of its own. These days I sleep about six hours a night. There will be periods—a week or so—when I don’t sleep much at all, maybe five hours a night or less. Then I might tick up to seven hours for a while. Eight hours almost never happens. I find if I go to bed early, I will wake up in the early hours and maybe listen to an audio story or even finish the movie I fell asleep to a few hours before—”the watch.” One thing is true, the more I think about sleep, the less I sleep.

During the nights between the days I spent researching and writing this essay, for example, sleep was scant. In contrast, during the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, and when so many others were struggling that newspapers carried articles giving advice to the suddenly sleepless, I started sleeping for eight or nine hours a night. Perhaps it was the monotonous rhythm of those days, of having nowhere to go or to be. I didn’t find myself worrying, for the scale of the threat was so vast. Nothing to do but let go.

Now, in middle age, I find myself surrounded by newly insomniac friends, for aging is a major cause of insomnia. Jet lag sharpens the desire to share stories. In Toronto, a woman told me about the cocktail of drugs she takes every night. “One day you’ll read about my death.” Another has started, in midlife, to smoke marijuana, now legal in that city and several states across America. In Vienna, a friend complained of the pressure of sharing a bed with her lover. Of reading by torchlight, like being 12 again.

In Cape Town, several time zones away from his home in Oakland, California, a writer I had just met asked how I had tackled my own insomnia. “I tried to forget about it,” I told him. Maybe a year later he wrote to tell me he was doing a lot better. He figured that worrying about money was what kept him awake in the early hours. So he examined his track record and told himself that if he had been okay so far, he would be probably okay in the future: “The skill of choosing to stop worrying about something,” he wrote, “is proving to be versatile and extremely valuable.”

This can only be true.

__________________________________

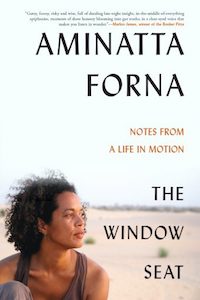

Excerpted from The Window Seat: Notes from a Life in Motion. Used with the permission of the publisher, Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic. Copyright © 2021 by Aminatta Forna.

Aminatta Forna

Aminatta Forna is the author of the novels Ancestor Stones, The Memory of Love, and The Hired Man, as well as the memoir The Devil That Danced on the Water, and the essay collection The Window Seat. Forna’s books have been translated into sixteen languages. Her essays have appeared in Granta, The Guardian, The Observer, and Vogue. She is currently the Lannan Visiting Chair of Poetics at Georgetown University.