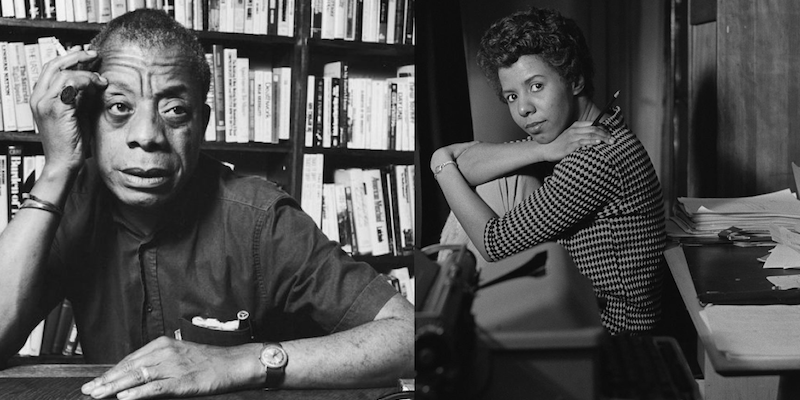

Charles J. Shields on the Profound and Playful Friendship Between Lorraine Hansberry and James Baldwin

“Baldwin loved her caustic wit.”

During that year of intense writing and rewriting, Hansberry became friends with James Baldwin. They met in April, at a workshop reading at the Actors Studio of his novel Giovanni’s Room, which he had adapted into a play. The work is about an interracial love affair. In America, Baldwin said, “the sexual question and the racial question have always been intertwined.” Lorraine went out of curiosity.

David, the narrator—“a good white Protestant” and heterosexual—lives in a mansion in the South of France. He describes what it was like falling in love with a darkly beautiful Italian bartender, Giovanni. But then David sees another young man and feels the same keen desire. Overwhelmed by this impulse, he finds his excitement leading to faithlessness, and the situation turns violent. David blames Giovanni, “the other,” for tricking him and damaging his manhood. “There opened in me a hatred for Giovanni which was as powerful as my love and which was nourished by the same roots.”

This is how David recalls events, but then, no one remembers things reliably because of their need for self-preservation and their perception of who they are. An important metaphor occurs when David studies himself in a mirror. Proud of his masculine appeal, he tells himself that he’s not like other people—not like Giovanni, who’s dark, instinctual, and lower-class.

Being white provides David with a mythology about superiority. “My reflection is tall, perhaps rather like an arrow. My blond hair gleams. My face is like a face you have seen many times. My ancestors conquered a continent, pushing across death-laden plains, until they came to an ocean which faced away from Europe into a darker past.” Giovanni’s Room, Baldwin said, is not so much about homosexuality as it is about the sadness of convincing ourselves that we’re incapable of loving others.

Only one attendee defended what she had heard: “a young black woman at the back of the small workshop audience,” Baldwin said.

As the reading at the Actors Workshop ended and the discussion began, most of the reactions to the play were negative. Baldwin sat listening to his work faulted again and again. Only one attendee defended what she had heard: “a young black woman at the back of the small workshop audience,” Baldwin said. “She had liked the play, she had liked it a lot, she said firmly. I was enormously grateful to her, she seemed to speak for me.” Afterward, he went over to introduce himself to Lorraine; his impression was that she was a shy but determined person. “She talked to me with a gentleness and generosity never to be forgotten.”

As it happened, they lived not far from each other—he was on Horatio Street, a ten-minute walk from Bleecker Street—and they began spending time together, usually at her apartment having drinks and listening to the Modern Jazz Quartet, one of their favorite groups. She was 28; he was 34.

Hansberry tended to be reserved around people at first, which some took to mean that she was cold. Harold Cruse, from the moment he met her at Freedom, decided she was “demonstrably anti-male, especially towards those she considered socially beneath her.” She tended to speak carefully, which could give the impression that she was unemotional. To her, conversation was supposed to move toward something, in pursuit of a point, or to clarify an issue.

You could see her thinking hard when she was feeling serious. An acquaintance said, “You had to know her pretty well to feel the great warmth she possessed. But there was great joy in this girl. She loved music, the dance, everything. And when she felt relaxed, in an environment where she could let herself go—she was a lively one—a lively one.”

Baldwin found this to be true. Hanging out at Lorraine’s apartment, the two enjoyed arguing and teasing. He was the eldest in his family, and she was the youngest. The way she picked on him affectionately, like a sister, tickled him. “Just when I was certain that she was about to throw me out, as being too rowdy a type, she would stand up, her hands on her hips (for these downhome sessions she always wore slacks) and pick up my empty glass as though she intended to throw it at me. Then she would walk into the kitchen, saying with a haughty toss of her head, ‘Really, Jimmy, you ain’t right, child!’”

They argued about Langston Hughes. Baldwin blamed him for wasting his talents on minor efforts. Hansberry defended him and cautioned Jimmy not to air his criticisms about Hughes in public, or about Richard Wright, either. It gave racists ammunition. Baldwin insisted that he had to say what he thought, especially when speaking to an audience. To “witness” meant telling people not what they wanted to hear, but what they needed to hear. “Relations between Negroes and whites demand honesty and insight. They must be based on the assumption that there is one race and that we are all a part of it.”

Hanging out at Lorraine’s apartment, the two enjoyed arguing and teasing […] The way she picked on him affectionately, like a sister, tickled him.

Lorraine knew that some of Jimmy’s feud with Langston was personal. Hughes resented what he considered Baldwin’s complicity in encouraging white people’s assumptions about black life—“the fakelore of black pathology,” writer Albert Murray called it. Harlem was home to Hughes; he accused Baldwin of capitalizing on it as a place to collect material, the grittier and uglier the better, for making dire prophesies about America’s future.

Hansberry also disagreed with Baldwin about Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam. He insisted that Malcolm’s was “the only movement in the country that you can call grassroots. When Malcolm talks or the Muslim ministers talk, they articulate for all the Negro people who hear them, who listen to them. They articulate their suffering, the suffering which has been in this country so long denied. That’s Malcolm’s great authority over any of his audiences. He corroborates their reality; he tells them that they really exist.”

Lorraine refused to give Malcom X, or the Muslims, that much intellectual credit. To her, as she later wrote, black nationalism “was a potluck nationalism that looks backward, not to the wonderful black African civilization of medieval and antique periods, but to Arabic cultures. Muslim ‘separation’ is not a program, but an accommodation to American racism.”

She and Baldwin were of one mind, however, about Norman Mailer’s essay “The White Negro: Superficial Reflections on the Hipster,” which had appeared in Dissent the previous fall. Mailer, writing in jazz-inspired bop prosody, riffs on the Beats, who aspire to a kind of Zen-like mindfulness.

They wanted to be aware, Buddha-like, without judgment, of every moment and feeling in a world that was seeking to depersonalize humanity. Human skin had been made into lampshades in Nazi death camps, and an atomic bomb nicknamed “Little Boy” had vaporized 45 thousand Japanese in a flash. To be Beat, wrote Mailer, was to channel all that madness, to “encourage the psychopath in oneself, to explore the domain of experience where security is boredom and therefore sickness, and exist…in that enormous present which is without past or future, memory or planned intention, the life where a man must go until he is beat.”

Lorraine dismissed the Beats as puerile and useless. They were disciples of “nothingism…They are a failure. They disturb no one because they attack everything and nothing…They serve no significant purpose, neither to art nor society.” They made bohemia seem clownish. She would later tell a college audience, “I am ashamed of the Beat Generation. They have made a crummy revolt, a revolt that has not added up to a hill of beans.”

White, college-educated hipsters experiencing an existential crisis were one thing. But they appropriated black pain in an effort to feel authentic. Allen Ginsberg declaimed in the Beat panegyric Howl, “I saw the best minds of my generation, destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix, angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night…”

“Perhaps they are angry young men,” Hansberry said, “but insofar as they do not make it clear with whom or at what they are angry, they can be said only to add bedlam to this already chaotic house.”

Mailer, for his part, a Harvard graduate in aeronautical engineering, could, Beat-wise, dig the Negro scene. He scratched his goatee, analyzed where the Negro was coming from metaphysically, and found him an enviable, fellow cat:

. . . the Negro (all exceptions admitted) could rarely afford the sophisticated inhibitions of civilization, and so he kept for his survival the art of the primitive, he lived in the enormous present, he subsisted for his Saturday night kicks, relinquishing the pleasures of the mind for the more obligatory pleasures of the body, and in his music he gave voice to the character and quality of his existence, to his rage and the infinite variations of joy, lust, languor, growl, cramp, pinch, scream and despair of his orgasm. For jazz is orgasm, it is the music of orgasm, good orgasm and bad, and so it spoke across a nation, it had the communication of art even where it was watered, perverted, corrupted, and almost killed, it spoke in no matter what laundered popular way of instantaneous existential states to which some whites could respond.

Article continues after advertisement

For Mailer, the power of black music lay in a presumably savage strain inside the black people who had invented it. A black jazz musician had told Baldwin that Mailer was “a real sweet ofay cat, but a little frantic.” Lorraine was less generous. She summarized Mailer’s and the Beats’ ideas about black people as “look over there coming down from the trees is a Negro” who knows none of the soul-killing constraints of civilization, “and wouldn’t it be marvelous if I could be my naked, brutal, savage self again?”

Baldwin loved her caustic wit. “I would often stagger down her stairs as the sun came up, usually in the middle of a paragraph and always in the middle of a laugh.”

____________________________________________

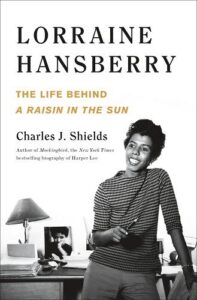

Excerpted from Lorraine Hansberry: The Life Behind A Raisin in the Sun by Charles J. Shields. Published by Henry Holt and Company. Copyright © 2022 by Charles J. Shields. All rights reserved.

Charles J. Shields

Charles J. Shields is the author of Harper Lee's New York Times bestselling biography Mockingbird, the Kurt Vonnegut biography And So It Goes, and the biography of John Edward Williams, The Man Who Wrote the Perfect Novel. Shields has spoken to hundreds of large audiences in schools, libraries, museums, and historic theaters and appeared in newspapers and magazines worldwide, including the Wall Street Journal, New Yorker, Huffington Post, and New York Times.