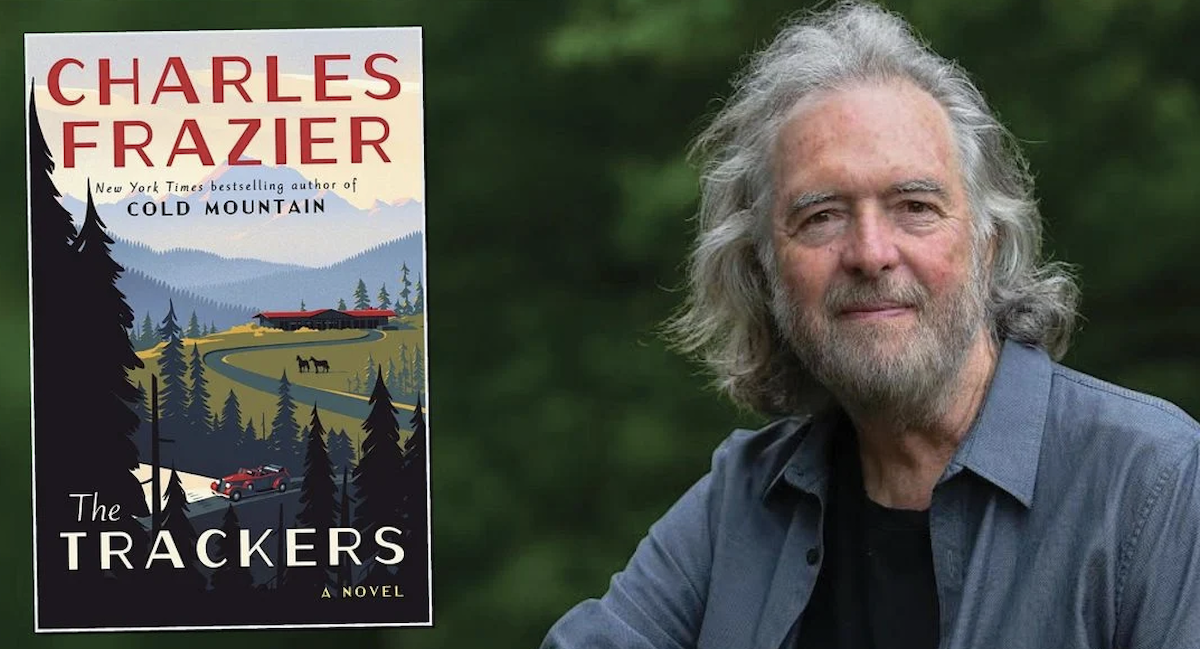

Charles Frazier on How the Past Converses With the Present

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of The Trackers

Charles Frazier, who will forever be known for Cold Mountain, his National Book Award winning, mega-selling 1997 first novel, opens his fifth novel, The Trackers, with an image that tells us exactly what we’re in for, and also reveals the author’s inspiration. “In a muddy black-and-white newspaper photograph I’m standing on a scaffold made from two tall stepladders with board running between them,” narrator Val tells us. “I’ve barely begun the mural, haven’t even started putting color on the wall of the brand-new post office.”

Val describes two onlookers—John and Eve Long, a prominent Wyoming rancher and his younger wife. Eve is wearing a “fancy show business cowgirl outfit.” The caption on the front page of the Dawes Journal read, “After Cheyenne trip, prominent rancher John Long and wife greet WPA painter.”

This photograph outlines the triangle at the center of the novel. Why begin here? I asked Frazier in our email exchange. “My ideas for novels tend to arrive in the form of an image, either seen or imagined, that pops up unexpectedly and then becomes unshakable,” he explained. “For The Trackers, that image was a photograph I saw about ten years ago. I wasn’t really looking for a book idea, but I walked into a small-town post office to look at a mural—Daniel Boone leading a wagon train headed west—and walked out intrigued.

At the university library nearby I spent two or three days looking at books on New Deal public art projects, and in one I found a photograph taken inside a new post office somewhere out West in the 1930s. Two youngish men stood on a scaffold improvised from two ladders and some boards. On the wall behind them, a mural was underway. On the floor beneath the young men stood a somewhat older man in a suit and, beside him, a well-dressed woman. I took some notes but soon lost the notebook.”

“Not long after,” he continued, “I started writing a different book, but I kept thinking about those four people and the setting of the photograph. Who were they and what connected them? There was a story there somewhere, at least the spark of one. The Great Depression, the Rocky Mountain West, horses and cowboys. Over time I read biographies of muralists from the period—Thomas Hart Benton and Diego Rivera. Eventually, one book and five years later, I decided to find out who those people in the photograph could be and what story they might have together. I dumped one of the younger men, or maybe I should say conflated the two, and moved forward. So the newspaper photograph in the book, that flashbulb pop, is a nod to the origin of the story.” Our exchange took place on the cusp of spring.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How have your life and work been going during these past years of tumult and uncertainty? Your writing? How was your work on The Trackers, and preparing it for publication, affected?

Charles Frazier: I’m generally fairly hermit-like when I’m deep into the daily writing of a book, so my days haven’t been awfully different during the pandemic, which I know makes me one of the lucky few. Parts of my writing process, though, tend to involve an element of travel, almost like location scouting for a movie. I go to real places where scenes could occur and take notes on what my characters might see and feel there, how they might inhabit the space.

I love the lore of making things and fixing things, the knowledge of it.

Fall of 2019, I began making plans to spend much of the following summer scouting for The Trackers in Wyoming and many other parts of the West, with stretches of actual writing scattered in as well. I had good luck writing in Jackson Hole before—in September of 1989 I wrote the first bits of what became Cold Mountain there.

When Covid first hit in spring of 2020, I thought or at least hoped that the pandemic would come and go quickly. But by summer, I began restructuring the story to focus on locations I could write about from memory, places I had known from way back—Wyoming, Central Florida, Seattle, San Francisco, and the Chesapeake Bay.

JC: What drew you to base the narrative of The Trackers on the experiences of a Depression era WPA muralist involved in a “New Deal art project, a post office mural—art for the people”? (Is there an actual WPA mural of “The Trackers” or one like it? Did you read the WPA state guides? WPA archives?)

CF: I was partly drawn to the Depression era and New Deal art based on stories my grandparents told when I was a kid about their experiences of the Depression, and the sense of hope many of those public projects gave in difficult times.

While there isn’t, as far as I know, a Depression-era post office mural called “The Trackers,” I did base Val’s fictional painting on multiple real murals in Western POs, borrowing elements from several of them—the basic underlying structure of the images, the ways painters dealt with the awkwardness of the space the mural had to occupy, etc.

I relied a lot on the WPA state guides for California, Washington State, and Florida to help shape Val’s journeys. They’re an incredibly vast and detailed source of information on what a road trip would have been like in the 1930s. The California guide alone is over seven hundred pages long. Also, the Living New Deal website is a treasure trove of information on public works projects—everything from the Blue Ridge Parkway to public art to improvements in sewage lines. I found their many photos of murals throughout the country to be extremely helpful.

JC: What sort of research was involved in detailing the artwork of your muralist Val—laying out the grid, his use of egg tempura (“If whites get mixed with yolks, you’ve got a problem”), and other specifics of painting the mural in the post office in Dawes, Wyoming?

CF: I love the lore of making things and fixing things, the knowledge of it. I can spend hours on YouTube learning how to service a two-cycle leaf blower engine, so, of course, I read a great deal more than I really needed to on mural making. Old stuff and new stuff. But the most helpful resource I found was a very good little film made in 1947 of Thomas Hart Benton—a major influence on many of the muralists of the thirties—making a mural. It shows his process in detail from start to finish and probably tells you most of what you need to know unless you’re actually a painter, which I’m not.

JC: John Long provides the lodging for Val on his massive Wyoming ranch, and reveals early on his aspirations toward a political position—perhaps as a Senator representing Wyoming in Washington, D.C.—as well as his experience as a sniper during World War I. Val also learns Long is involved in the coming of the electrical grid to the state. He’s both fascinated and repulsed by Long. Were your intentions to explore the seductive qualities of those who seek power? And to show the underside, in the shadow?

CF: Yes, at least partially. I wanted Long to have some of the ambition and seductive skills of a successful politician, and I wanted Val to feel a complicated mix of envy and admiration and resentment and repulsion toward him. Also, I was interested in exploring the Depression era from multiple economic perspectives, so Long’s family wealth and privilege offered a different experience from Val’s and Eve’s. As the novel developed, I became more and more curious about the ways Long’s ambition affected his relationships with the other characters, and especially how any resistance to Long’s sense of his own power caused shifts and ripples throughout the story.

JC: Eve is a woman who comes of age during the difficult Depression years. She has the gumption to go on the road as a female hobo riding the rails and finding work where she can, until she discovers a gift for singing and inhabiting the stage. Her years traveling with a country band prepare her to be a glamorous singer who could make a charming sidekick for an aspiring politician. What makes Eve so courageous? And so difficult for anyone to hang onto?

Sometimes it’s useful for me to see a book in terms of geometrical shapes.

CF: Eve’s personality and behavior are deeply influenced by the Depression. She leaves home part way through high school when she realizes her parents can’t afford for her to stay. Being out on the road as a young woman during the worst of times—hitchhiking and hopping freights from coast to coast looking for work—was dangerous and required an enormous amount of toughness and hardness, self-reliance and intelligence. Eve is above all a survivor and proud of it. Those qualities are partly what attract Long and Val and Faro to her, but the same qualities also send her packing when she feels threatened or caged.

Sometimes it’s useful for me to see a book in terms of geometrical shapes. This novel is an arrangement of interlocking triangles, and at the apex of each one is Eve. She is the reason all of those triangles exists. So while Val may be the storyteller, I’ve always considered Eve the main character of the story he tells.

JC: Here’s how Val describes his design of “The Trackers”: “A sweep, a wave of time passing, cresting in the center with a trio of trackers—two Crow guides and John Colter. In planning I had wanted those three figures to give the mural its title and for that image to embody the hinge of time in this place, that moment not far past first contact between the Plains Indians and the whites, the point where everything changed except landscape and weather.” What drew you to choose this pivotal moment in the history of the West for his mural?

CF: Many of the New Deal murals took the local economy as a major part of their subject matter and aimed, it seems, for a rosy take on the development of that economy. I wanted Val to look more toward the fundamental history of the place, the moment when white people showed up and violently stole the West, a moment before the myth of the Old West arose and papered over the horrible truth with the image of the intrepid survivalist out conquering the landscape alone. A difficult goal to achieve with a committee-approved, publicly funded mural, but I wanted Val to have the impulse to try.

JC: Val admires muralists like Diego Rivera and Thomas Hart Benton, whose work was highly visible in the Depression era. How is his design for “The Trackers” influenced by their work?

CF: I imagine that if you could see Val’s painting, its influences would be fairly apparent. Maybe too much so. I think he would have gotten ideas about color and composition from both painters. And I’m fairly sure he aspired to a feeling of fluidity in figures and landscapes from Benton and a sense of weight and monumentality from Rivera. How well his influences worked together, I’m not sure.

JC: Eve disappears, taking Long’s Renoir painting. Long sends Val on her trail, to Seattle, including its Hooverville homeless encampment; to Tampa, the Florida swamps; and to the San Francisco Bay Area shortly after the Golden Gate Bridge was built. You have vivid scenes in each of these regions, including a drive down Highway 1 around Half Moon Bay, all capturing how it might have been in the 1930s. What was your process for researching and writing Val’s journeys?

CF: Most of the locations Val visits are places I know pretty well—especially Florida and the Rockies, having lived for years in both areas—so accessing my old memories of things like weather, light, color, and the seasons was part of building a sense of place. There was also, though, a great deal of research. I’ll use Val’s round trip flight from Denver to Tampa as an example.

Commercial airline travel was still relatively new in 1937, and I knew nothing about the subject. So I made an itinerary for Val’s trip and began piecing it together from there. How long would the trip have taken? How many stops? What were the planes like and the airports? I looked at old flight schedules, photographs, film clips. I read a number of accounts of air travel by passengers and pilots to get a sense of how miserable long-distance flights would have been in the days when planes flew much slower and lacked pressurized cabins and only got up to about eight thousand feet, so there was no such thing as flying above bad weather and, in a time before sick bags, every seat had a basin underneath. The icing on the cake of that research was finding a bit of video from the cockpit of a small plane descending over Tampa and landing at the old airport, which would have been brand new when Val arrived there.

JC: The fourth major character in this novel is Faro, a Wild West carryover who works on John Long’s ranch, a gnarly elder with a rapid-fire punch and a wizard-like expertise with guns. As Val puts it, “He’s from the last century. People were all strange back then.” How did you piece together Faro as a character, including his particular moral stance?

The farther I went in my reading the more the similarities became impossible to ignore.

CF:I wanted Faro to be at once an embodiment of the myth of the old frontier West and a dismissive critic of it. He laughs at townspeople who gossip that he was the young soldier who killed Crazy Horse or helped Billy the Kid fake his death and escape to Mexico, and yet he’s very knowledgeable about the Lincoln County War in New Mexico where Billy Bonney made a name for himself. In other words, the myth of Wild West that became such an important piece of American culture and sense of self means nothing to Faro. He has a very specific code that he lives by, but he’s seen enough violence and stupidity and injustice in his long life that he’s become both cynical and a tiny bit idealistic in his old age.

JC:The Trackers is Val’s story, and it’s also a coming of age tale, as he explores the land beyond the Chesapeake Bay, where he was raised, and discovers the deepening struggles in Depression-era America and the massive financial divide. “The Depression had gone on so long it had become divided into epochs. The horrible shocking months after the crash, the dreary years afterward, the hopeful months and, then the dreadful backsliding of the economy toward hopelessness…” While working on The Trackers, did you find ways in which that period in American history mirrors our own? Were you motivated, energized by this resemblance?

CF: I didn’t start out looking for similarities between then and now, but the farther I went in my reading the more the similarities became impossible to ignore—issues like racial and economic inequality, fractured and fractious politics, the environmental disaster of the Dust Bowl, the threatening rise of fascism around the world, the deeply political Supreme Court. I’d say I was more energized than motivated by the similarities.

JC: Do you have a new project in the works? What are you doing next?

CF: After the book tour is over, I hope for a couple of months of riding my mountain bike on my favorite trails and fire roads and reading a lot of books I’ve missed the past four years. After that, I have a couple of images I’d like to follow—snow and a sled, a military encampment beside a public swimming pool.

__________________________________

![]()

The Trackers by Charles Frazier is available from Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.