Catharsis, Harpies, Harmatia, and More: Natasha Pulley on Her Favorite Greek Words

The Author of “Hymn to Dionysus” Explores a Linguistic Venn Diagram of Meaning

During the pandemic, I started writing a book about the Greek god Dionysus. I’d always wanted to, because I think he doesn’t get even half the attention he ought to in comparison to all the other gods we see in myth retellings…not to mention that he’s the god of something brilliant (spoiler: it isn’t just wine).

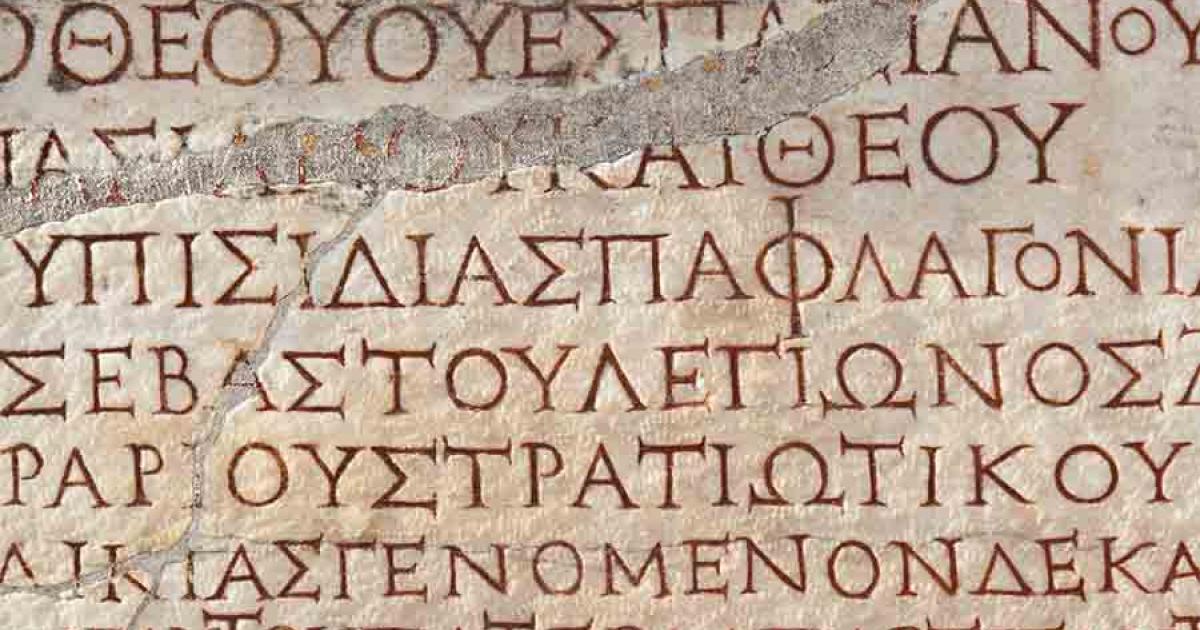

But even though all the texts about him have been translated into English, I felt like I was seeing only a partial image of him and the world he came from. English is a peculiar, patchwork language, and English translations of Greek texts can be treacherous, filled with all kinds of misleading not-quite-mistranslations, especially if the translation was done a while ago. So, I bought myself some textbooks, and learned enough classical Greek to read some of my sources in the original.

I’ve been told this is not normal behavior, but I loved it. One of the reasons I had so much fun is that if you start to compare words that mean the same thing across any two languages, something truly fascinating happens.

Although words like “cat” or “hill” will fit exactly, when you move into ideas, feelings, colors, or anything else that sits on a spectrum, they nearly never do. What you find is more of a Venn diagram of meaning, with an overlap that the speakers of both languages understand…but outlying shades on either side that don’t line up.

Whenever I learn a new language, my favorite thing is looking for those words. Often, the shades that don’t match are the ones that will make you cry yourself to sleep at night, but they’re also the ones that are most revealing, because what they show is something invaluable: the difference in what different languages prioritize, and therefore the way they’re encouraging their speakers to think.

Here are some of my favorites in Greek.

*

Catharsis: I love this word, because I love everything to do with Dionysus, and catharsis is what he’s all about. Very roughly, it means something like “release”…but that’s misleading in English. It also means “purification” or “purgation” in a medical, religious, and ritual sense, and translators famously struggle with it because the meaning is so nebulous.

It’s especially important in theatre and storytelling. The whole function of a tragic play, Aristotle says in Poetics, is catharsis.

Intriguingly, the great Athenian festival of theatre was called the Dionysia, and the plays were dedicated to Dionysus: scholars disagree about why, but it makes a lot of sense to me. Drunkenness, temporary madness, theatre, sex…all of these are associated with Dionysus, and all of them are about a release: the feeling that you’re letting something go and being restored because of it.

Harpy: Lots of us have heard of harpies, the scary winged ladies with talons. The word probably derives from the Greek “harpazien,” “to snatch”—so harpies are “snatchers”—but brilliantly, “harpy” is also used of whirlwinds.

When some writers, like Herodotus or Lucian of Samosata, talk about sailors seeing harpies raging over the sea, they’re seeing cyclones. Harpies are associated with storms and high winds because of the violence of their flight, so the same word comes to be used for the weather and the monster.

Drachma: A drachma was a unit of currency and later a coin, but literally it means “a handful” or “a grasp,” and originally it referred a handful of oboloi—two foot spears of bronze, iron, or copper, which were used as money. This was wildly impractical, perhaps on purpose.

At least in Sparta, there seems to have been a serious doubt around whether any kind of standardized currency was ever a good idea, even though wider financial transactions in the Mediterranean were often done in talents—a unit of weight—of silver. Making money incredibly hard to use might have been one strategy some Greek states used to discourage the whole idea of a cash economy.

Hamartia: We’re often taught at school that hamartia means a fatal flaw, but it’s a devious word. In classical Greek, it’s an archery term: it literally means a “miss,” as in, to miss a target—so, a mistake, or a miscalculation.

In the Iliad, Achilles’ hamartia, his mistake, is that he goes on strike and doesn’t have the foresight to realize that Patroclus will take his place. That’s assuredly a bit thick, but it isn’t a fatal character flaw: it’s bad judgement.

A plot twist though: five hundred years on, by the time we get to the New Testament, the same word has shifted its meaning. In the Bible, hamartia means “sin.” It’s very tempting to apply that meaning back to classical texts…but Achilles’ pride isn’t framed as a sin in The Iliad, and nor is Oedipus’ ignorance about the circumstances of his birth. These are just understandable mistakes that have horrifying consequences.

Khalkos: This means bronze or copper, but it’s also famously the color that Greek used to describe the sky. There’s no word for blue. This is a lovely illustration of just how differently languages draw the boundaries between colors.

In Old Japanese, “aoi” is green and blue, a kind of general nature color. Russian differentiates between dark and light blue in the way English marks a difference between red and pink…and some languages, like classical Greek, prioritize brightness or darkness over hue. It doesn’t mean people see differently, just that they think differently about what they’re seeing.

Greek did have a word sometimes used for what English would call blue, “kyanos”, from which we derive our word “cyan”…but it’s tricksy. “Kyanos” was used of lapis lazuli, but in the Homeric “Hymn to Dionysus,” Dionysus’ eyes are “kyanos” too…and so is his hair. Unless he had blue hair (probably not, disappointingly), it just means a rich, dark color.

______________________________

The Hymn to Dionysus by Natasha Pulley is available via Bloomsbury.

Natasha Pulley

Natasha Pulley is the internationally bestselling author of The Hymn to Dionysus, The Watchmaker of Filigree Street, The Bedlam Stacks, The Lost Future of Pepperharrow, The Kingdoms, and The Half Life of Valery K. She has won a Betty Trask Award, been shortlisted for the Authors' Club Best First Novel Award, the Royal Society of Literature's Encore Award, and the Wilbur Smith Adventure Writing Prize, and longlisted for the Walter Scott Prize. She lives in Bristol, England.