Carving Our Canoes: On the Value of Building a Communal Life in an Atomized World

Tyson Yunkaporta Considers the Possibilities and Limits of Indigenous Knowledge For Relieving Contemporary Malaise

I’m a younger sibling. My elder sister Delys speaks for me, and my big brother Steve speaks for the stories we carry together. There are a lot of brothers and sisters and cousins, and when we see each other in the distance some of us might call out, “Brolga brolga brolga!” and answer, “Kor’ kor’ kor’!’” because that crane is a bird that binds us in common totemic relation. That doesn’t mean everything is peaceful though.

Families fight, families split, families harm, and these days the old mechanisms aren’t always in place to stop this. Like everybody in the world, we are struggling right now. There is no sovereign paradise to be found anymore—just mining and pastoral leases encircling villages where the only growth industry is policing.

Dad is known as Rambo because he was wild like me in his youth. He is a church elder now. Mum passed away a few years back. But there are lots of mums and lots of dads, as their brothers and sisters are known to me in this way, and they all grew us up. They only started raising me (as an Aboriginal boy of orphan/tribeless status) in my late twenties, so I’m a bit of a late developer, even though I’m fifty now.

My siblings and I grow up our own children and a lot of nephews, nieces and grandchildren, who also have children that we all care for together, often taking them with us in our travels. This is most of our work. The rest is acquiring enough money to feed, shelter, equip and educate everyone. Sometimes there is time to care for country and do ceremony, too. But not much.

My web of relations is what allows me to write this book, what constitutes me as a human being. Without that, I die.

We all try really hard, but I tell you, I’m sick of hearing this rubbish statistic about eighty per cent of the world’s remaining biodiversity being diligently cared for by Indigenous Peoples. Most of us have only nominal Native Title and no real control, “co-managing” the land at best, in ways that facilitate mining or agricultural interests, while we struggle to feed and shelter ourselves in the economy of the occupying culture. That doesn’t leave us much time to look after the shred of biodiversity left in their water reserves, agriculture complexes, real-estate developments and mining leases. Our family does continue this work in our sacred places (the ones that haven’t yet been blown up or bulldozed), but it is very hard to cram it all into a weekend.

Our brolga story is connected to a sacred site called Moving Stone, and also a lot of other places along that songline—the narrative map in the landscape that holds clan knowledge and history. This also connects us to the Rainbow Serpent, lightning, storm, blood, urine, waterlily, mudshell, black cockatoo and more. These are all entities that exist in relation with us.

We are linked to other families in other clans as well, along with many people from other areas far afield. We often travel and stay in these places with them, sometimes for many years. We often adopt or marry into those places and families and stay there forever. One of my many nieces is currently going through the process of full customary adoption into a family in another community. She will take on their name and bloodlines, and we will be sad to lose her, but also happy to be strengthening connections and interdependent relations with this other Country.

In our culture we know this is the best way to avoid the emergence of imperialism and industrial warfare—which is why we’ve always had battles, but never had wars. Adoption and marriage across groups is a sacred thing, and it works better for us than it does in Game of Thrones. I have one uncle who went to Mornington Island years ago and never came back! But that was about a woman…

Same thing happened to me recently, which is how I finished up 3,500 kilometers south of home, suddenly in the city but madly in love with my spouse Megan. We have two babies together now and I’m stepfather for her daughter too. Megan is related to the Smiths and Mitchells from the Baradha people in central Queensland. I think I fell in love with her because she has as many scars as I do, and that means we can read each other’s bodies like Russian novels. She is an active participant in many of the yarns in this book.

I have both strong affiliations and older, broken ties with Indigenous relatives far from my home, many different relationships from distant relatives to close cultural connections, in the south and west of Australia. In healthy Aboriginal social contexts, we would say all these names upon introduction over the course of many hours or even days and nights, and try to figure out how we connect down to one degree of separation, so we know what to call each other in relational terms, but this isn’t really possible for the international audience reading these words, so I might leave that protocol out. I’ve already worn out my welcome in the word-length of this opening chapter. But you get the idea. My web of relations is what allows me to write this book, what constitutes me as a human being. Without that, I die.

Despite devastating disruption and dysfunction, our Indigenous grapevine and social networks are still so strong on this continent that I have never found myself more than a few days’ walk away from people who are known to me and will give me shelter and food if I need it. It’s like an Aboriginal Airbnb but truly decentralized, needing no server or platform or electronic signal. This living network is what allows me to write sometimes.

Community comes together and a Murri fella says he’ll take over for me at work, a Palawa woman says she’ll help look after my babies, Djadjawurrung people bring me into their land with smoke and serpent story, and a Gumbaynggirr man living there gives me use of a little shack he’s built in the bush, which is where I’m writing from now.

There is a community of Indigenous wood carvers who congregate around this place, so although I’m far from home, I feel like I’m with my people. We’re carving these stories together, but they also have a forge here to make steel boomerangs like the one in Mad Max 2. Apocalypses are unsettling things, but they become much more interesting if you have prepped by stockpiling relationships rather than guns, gold and vitamin supplements.

That relational web we have in our Indigenous communities is a hell of a social safety net, when it’s allowed to work properly. It also informs our governance, economies, laws, information storage and diplomatic relations in some pretty wonderful ways that are worth considering at a time in history when most of the world is trying to reboot its failing institutions.

Us-two, you and I meeting in these pages, we’re here to find what is useful and interesting in dialogue. We’re not here to score points in a culture war. If I’m talking about failing global institutions and destructive empires, that’s not about individuals or communities or cultures—it’s about systems and structures that we are all required to live under at this moment in history, and most of us are intensely unhappy and terrified about it all. I’m not sitting down here with you clutching my historical IOUs; I’m here to share some stories, patterns and systems that might be helpful in the next few decades (and even centuries).

In the extended-family canoe story I just shared with you, you can see the processes of a non-centralized knowledge economy embedded in a kind of cognition distributed throughout creation, that carries all knowledge production, transmission and memory. These things are managed within intergenerational relationships in bioregional collectives (both within regions and between interrelated syndicates of regions) stretching across all of time. Knowledge shared within the processes and protocols of this relational economy is something I think of as ‘right story.’

Right story is not about objective truth, but the metaphors and relations and narratives of interconnected communities, living in complex contexts of knowledge and economy, aligned with the patterns of land and creation. Right story never comes from individuals, but from groups living in right relation with each other and with the land. Wrong story, wrong way—this means unilateral or unbalanced ritual, word and thought.

So, in exploring the pathologies of a world in wrong relation, I have to tell wrong story in this book. This means sharing stories made by individuals or corrupt groups separated from land and spirit (and these include both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people). To understand the perverse incentive systems currently burning our world, I need to carve some objects the wrong way to spark the emergence of cautionary tales. Carving tools and weapons is how I keep (and communicate) my stories, right or wrong, so I usually need to make at least one new carving for every chapter. Most of these ones won’t be anything you’d want to hang on your wall.

These pages and carvings of stories aren’t talking about the way things were in the good old days, or even the remnant cultural processes that still work well for our Indigenous communities today. These knowledges are present, but they inform the lens for our inquiry into the state of the world.

They don’t provide exotic content to be consumed by readers looking for ancient wisdom. Ancient wisdom may provide examples of healthy models of governance, economies and technologies, but these can’t really help at the moment unless there is a through-line to now. These things can only help if examined alongside stories of development, growth, cybernetics, liberalism, modernism, post-modernism, post-truth and the other dominant abstractions that are shaping our reality.

So I have carved a wrong canoe. This wrong canoe will carry all the other carvings, objects, maps, relations and stories (good and bad) that make up this book, because we’re going on a journey here—hell no, an Odyssey—and many of the stops before the final shore will not be lovely places at all.

This canoe looks similar to the one in the right story above. The only difference is that it has mostly been made by an individual, and that changes everything. The community process of canoe-making is being damaged in the carving of this object.

We have to be realistic and acknowledge that ‘ancient wisdom’ is not your one-stop shop for salvation through regenerative design.

In this death by a thousand cuts, every chip of wood is confetti in a celebration of the global marketplace in which we all compete to survive—the rugged individualism, the sheer audacity and self-annihilating work ethic that it takes to win this economic game of musical chairs. It’s really hard. Myself, me, my own, I-only, disconnected in this particular activity because my spouse is looking after the kids while I take off for half a day to show the world how special and worthy I am, instead of fulfilling my obligations to family.

It’s dog-eat-dog here. I have failed to acknowledge Johnny Charles, the Ngarrindjeri fella who did half the work for me on this canoe. I’m in a city, thousands of miles away from my extended family, and while the money I can make here is keeping family members from hunger and poverty, it’s a poor substitute for my neglected duties as an uncle, father, brother, nephew, son, grandson.

Limited supply, high demand. In this marketplace, success means rolling the dice in a high-risk activity that may not pay off. I (only me!) am making this canoe on a university campus, breaking workplace health and safety regulations by refusing to wear goggles and gloves or use the useless rubber mallet they’ve asked me to carve with (for safety and security). But I’m a rebel! I’m a change-maker!

There is tension between the creative source and the extractive activity, for sure. There is the caring for community, land and culture that produces these skills in perpetuity (bad for business) and then there is the economic necessity to make products by and for individuals, products that must be limitable and excludable in order to have a price. It’s nothing personal, but lands and communities must be destroyed in order to produce value. We have to exclude people and cut off relations to value-add the hell out of these products, which are far more than cheap trinkets to mass-manufacture for profit. Oh no, this is art, little trophies destined to be somebody’s capital. These are not commodities, but stores of value. Wealthy outsiders can launder their cash through these unique items.

Boom and bust cycles are for day-traders and wannabes, but art and artifacts are a stable investment for the wealthy, along with gold and land (and, more recently, water rights). So here I am, making this object to become somebody else’s capital in a way that kills our cultures and communities and land, because the endgame of this process is ‘the last’ canoe, which will be a priceless artifact and store of much value. This reflects a lot of the wrong story upon which our current global economic system is built. Objects only have value when the people and places that produce them are damaged or destroyed in their production. After all, if every community could make one of these whenever they liked, then they’d be worth nothing at all.

All this wrong story is moving towards an important message: there are some inefficiencies, multipolar traps, perverse incentive structures and self-terminating algorithms in the current global system that could use some analysis from an Aboriginal point of view.

At the same time, we have to be realistic and acknowledge that ‘ancient wisdom’ is not your one-stop shop for salvation through regenerative design. It is easy and comforting to assume the hypothesis that this ancient method of inquiry and holistic knowledge system will contain all the answers. But it probably doesn’t. Moreover, on my own, I do not have the skills, knowledge, perspective, cultural competence or qualifications to undertake any such analysis. I do, however, belong to a vast web of relationships made of yarns and connections, and that entity certainly is capable of the computational work necessary to examine the complicated systems that are currently burning our world.

Us-two, knowing where (most of) the crocodiles are, can now start dragging our canoe down to the dark, stinking river where we begin our ill-advised hero’s journey. That’s if our massive behinds can still fit in it—I didn’t factor in the liquor store and KFC up the road when I was calculating the width of this thing.

See, those who ignore wrong story will inevitably be thwarted by it.

__________________________________

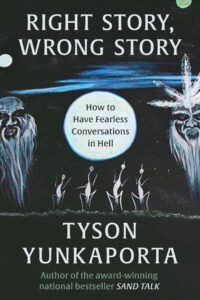

From Right Story, Wrong Story: How to Have Fearless Conversations in Hell by Tyson Yunkaporta. Copyright © 2025 by Tyson Yunkaporta. Available from HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Excerpted by permission.

Tyson Yunkaporta

Tyson Yunkaporta is an academic, an arts critic, and a researcher who is a member of the Apalech Clan in far north Queensland. He carves traditional tools and weapons and also works as a senior lecturer in Indigenous Knowledges at Deakin University in Melbourne. His first book, Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Change the World, was awarded the Ansari Institute’s Nasr Book Prize on Religion & the World awarded to an author who explores global issues using Indigenous perspectives. He lives in Melbourne, Australia.