Carson McCullers on Suicide, Psychiatry and the Mind of the Artist

"I think I don't believe very much in psychotherapy for creative people."

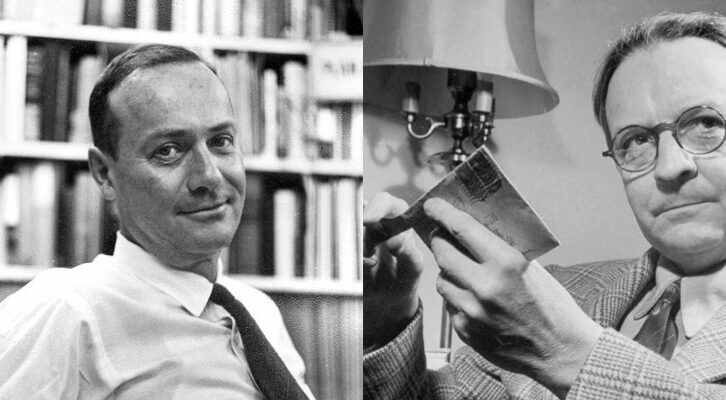

Carson McCullers died fifty years ago, at only fifty herself, and left behind a small but potent body of work—all the more impressive for the conditions under which she wrote it. She was plagued by illness throughout her life, including rheumatic fever and a series of strokes that began when she was twenty-four and left her partially paralyzed on her left side. She also suffered from alcoholism and severe depression, and in 1948, soon after her paralyzation, attempted suicide. A few years later, her ex-husband and sometimes-lover, Reeves McCullers, asked her to commit to a suicide pact with him. She fled, and he went through with it alone. But before all that, McCullers sent this letter, postmarked April 14th, 1948, to her friend, the psychiatrist Dr. Sidney Isenberg, in which she muses on the responsibility of psychiatrist to the artist, whether writing is neurosis or sign of heath, and anxiety as an essential facet of the human experience.

Dear Sidney,

Your charming letter reached me when it was à propos in a dismal way. I could not answer it at once, for any letter I might have written then would have been a cry for salvation. I was in Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic—where I remained for 3 dreadful weeks. You see these last exhausting months of illness had got me into an emotional, unhinged state. One night, in a fit of transient melancholy I slashed my wrist. My medical doctor thought I needed hospitalization. So I had to go to Payne Whitney.

There I was fixed in a vacuum, unable to try to help myself. I could not write, or read undisturbed, and was allowed no veil of privacy. It was like [Kafka] without the hope of ultimate salvation. I suffered intensely until finally a great dear friend of mine who is a psychiatrist decided my mother to take me away.

I have no suicidal tendencies and I will never hurt myself again. I was just over strained and fearful after this long illness. I had a vascular spasm that [has] left me still pretty paralyzed. I long to be strong and well. I have had so much illness, and have almost lost the hope of health.

I wonder how it would feel to be a psychiatrist. The responsibility is so immense. Are you ever afraid of this power? I had an excellent, kind doctor at Payne Whitney, but the head doctor is a Swiss peasant without a spark of insight—I dreaded talking with him. I had never known such a feeling of helplessness as I had there. I think I don’t believe very much in psychotherapy for creative people. The artist’s hallmark is the product of his inner conflicts. I do not want my internal chemistry changed, even though I may suffer.

It is absurd to say I don’t believe in psychotherapy—I mean that I intend to maintain my grasp, of my own soul—however fragile that grasp might be, as long as possible.

The head doctor at the clinic said I was not “facing” my ill health and questioned me about my defenses. When I said that writing was my bastion there, he insisted that work was not enough. To him writing is (sylogistically) as neurosis. While to me, the act of artistic creation, is the prime expression of health that I recognize.

. . .

You might call my condition a somatic-psycho state. But, since my emotional attitude will not possibly alter my vascular defects, I think it best to forget my infirmities and concentrate on something responsive that offers the possibility of some solace—work.

. . .

The true artist and the psychiatrist are concerned with the same subject—man in his relation to the human condition. On this subject—psychiatrists regard anxiety as an individual, neurotic “problem”—while I believe anxiety is an essential basic part of the conditions of human existence. We fear the acknowledgement of finity. There is always a tendency to reclaim the state of non-responsibility, the animal infinity that we lose when staking our claims to a soul.

Does this have meaning to you?

From the collection at the Washington and Lee University Library.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.