Capturing Process and Industry in America: On the Photography of Christopher Payne

Kathy Ryan on How "the Manufacturing World is Payne’s Muse"

Christopher Payne was en route through Brooklyn on his way to the MTA Overhaul Shop in Coney Island, where they rebuild and maintain subway cars. As he passed storefronts, bodegas, and restaurants, he commented, “‘STEAKS, CHOPS, SEAFOOD’—you don’t see that on the signs for diners anymore.” Payne is renowned for his photographs documenting industry in America. When he creates images of things being produced, he feels the urgency of knowing that all manufacturing processes change and disappear over time. He conveys the power and beauty of making things. All sorts of things: Steinway pianos, Whirlpool washing machines, Kohler urinals, Airbus planes, and electric vehicles shuttling down the assembly lines at Ford and Rivian. His focus ranges from traditional processes serving niche markets to ultramodern technologies.

Payne had photographed in the MTA Overhaul Shop several times already. In the cavernous skylighted space, he had the swagger of someone who understands the work done there, which won the respect of the workers. They knew from previous shoots the exactitude and precision—the eccentricity—he exhibits when composing a photograph. In his steel-toed boots and hard hat, Payne stalked the aisles lined with trains like a museum curator searching for treasures to put on display. Today his mind was set on a forty-ton subway car. He wanted to document the moment when the train is hoisted into the air to facilitate work on its undercarriage. Payne envisioned a moment when the elevated car would align with the car behind it in a way that would be deeply satisfying. This moment of geometric and compositional sublimity had eluded him so far. He is a perfectionist.

There is nothing loose or improvisatory about Payne’s work. As we entered the shop that morning, he said, “We’re going to get medical with this—like, surgical.” He will return to the same location five or even ten times in pursuit of an imagethat is escaping him or to redo an image he thinks he can do better. That’s what he was up to this day in Brooklyn. He set up his tripod and, as he was shooting, he directed the men moving the car into position to lift it a few inches higher here or drop it a few inches there. They endured several rounds of his requests because, as much as he admires the tremendous skill they bring to their labors, they seemed to admire the obsessive, sometimes baffling perfectionism he brings to his art. At one point, as he kept honing the exact composition he wanted, he said, “I don’t know if I am chasing something that is unattainable.”

Red/blue editing pencils before dunking in blue paint. General Pencil Company, Jersey City, New Jersey

Red/blue editing pencils before dunking in blue paint. General Pencil Company, Jersey City, New Jersey

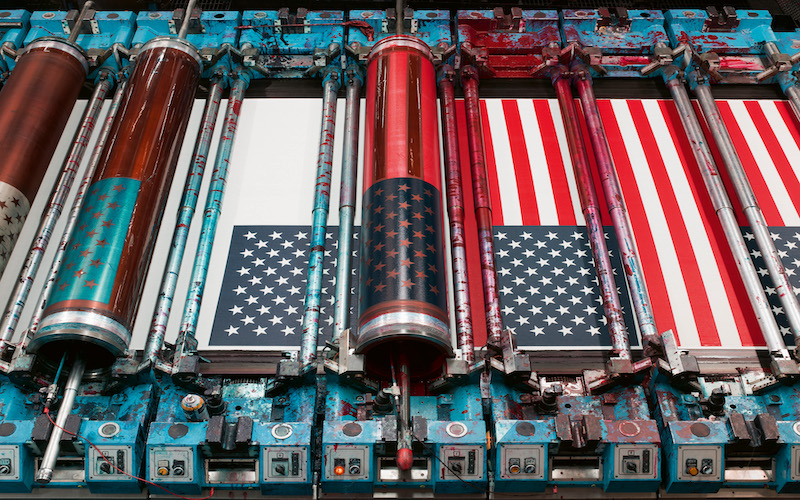

It was thrilling to see the colossal subway car handled like a toy. Scale plays a major role in Payne’s work. Pencils in a factory in Jersey City look monumental, and a row of airplane fuselages on an assembly line in Wichita, Kansas, looks tiny. He shoots behemoths like nuclear submarines, wind turbines, and printing presses with the same flair and eye for detail he brings to shooting tiny fiber optics and computer innards. The steel-and-copper hatch of a nautical submarine could be, at first glance, a watch component. One of his most delightful photos shows a man inside a huge New York Times printing press, engulfed by the tangle of wires, cables, and gears he is cleaning. Payne loves seeing humans inside machines.

Circular forms appear regularly in Payne’s pictures. A worker’s tiny legs peek out from below the huge steel sunflower of a jet engine. Rows of massive wheels are lined up in a locomotive factory in Fort Worth, Texas. Hundreds of spools of wire are mounted on the spokes of a gigantic orange wheel in the Nexans high-voltage subsea cable plant in Goose Creek, South Carolina. Chartreuse golf balls whirl- ing in a vibrating buffing chamber at the Titleist factory become graceful minimalist sculptures. One imagines him walking onto a factory floor filled with machinery and feeling the same jolt of inspiration that Monet once felt gazing at water lilies and van Gogh felt in a field of haystacks. The manufacturing world is Payne’s muse.

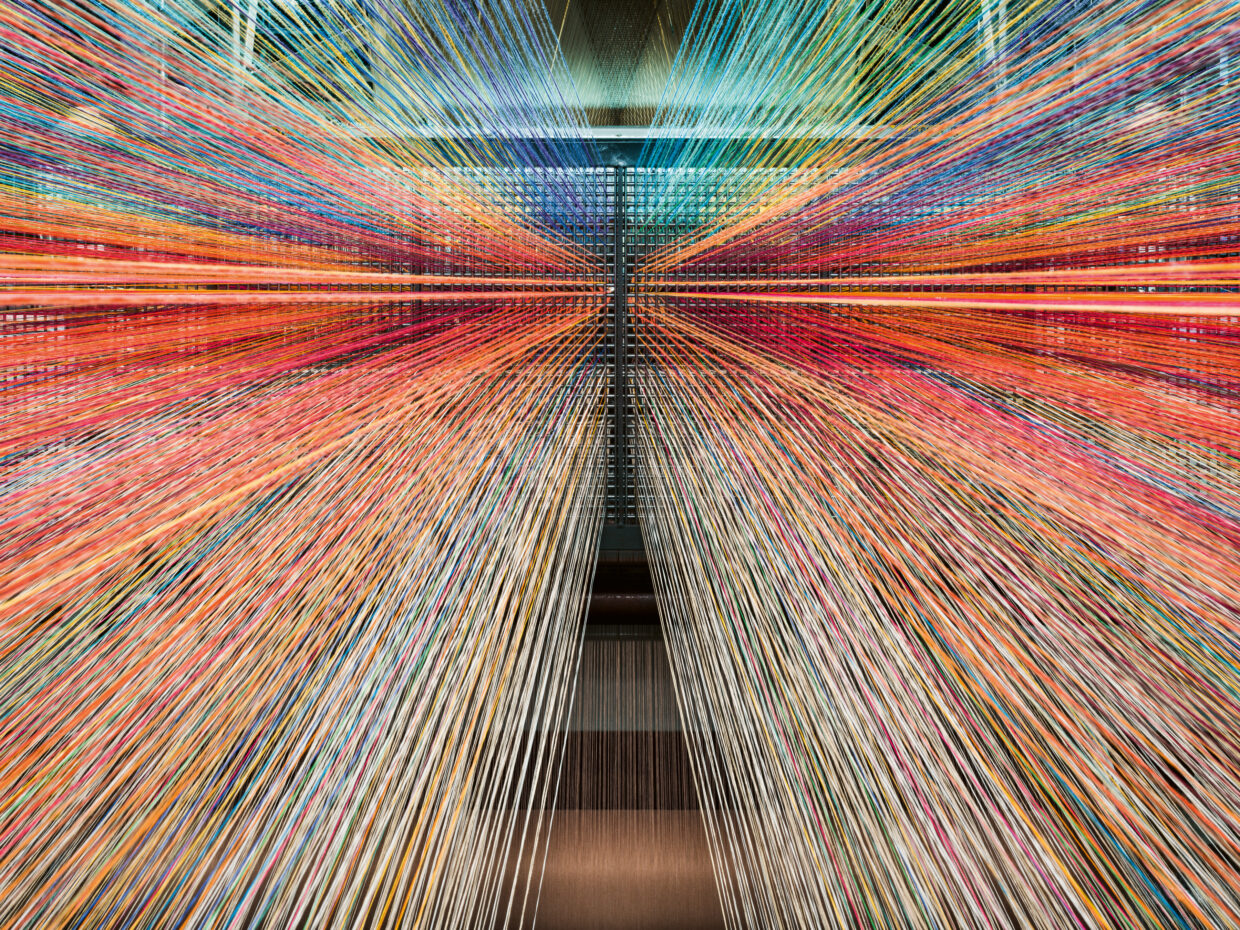

In 2010, a yarn mill in Maine caught Payne’s interest. The once-booming textile industry in the United States had shrunk dramatically in recent decades, and one of the main obsessions that fuels Payne’s art is the desire to capture traditional manufacturing processes before they disappear. The mill became the first of more than twenty that Payne documented throughout New England. One morning he received a call from the owner of the S & D Spinning Mill in Millbury, Massachusetts, a place where Payne had spent some time. The owner said, “You might want to come up today. We’re running pink.”

Wool carders. S & D Spinning Mill, Millbury, Massachusetts

Wool carders. S & D Spinning Mill, Millbury, Massachusetts

Prior to that, whenever Payne had been on-site, they were running black, white, and gray wool. Payne, who lives in upper Manhattan, still chuckles when he recounts thinking to himself, “Do I want to give up my parking space right outside my apartment to drive three and a half hours to the mill?” Of course he did. He made one of his iconic photos that day—a deliriously pink sea of unspun fuzzy wool fiber stretched across a bank of gray rollers cascading down from the ceiling. The interlocking lines and angles formed by the grid of rollers, ladders, fencing, and vividly magenta gossamer fibers form a rhythmically harmonious composition that would hold its own against a rigorous Mondrian-esque abstraction if it weren’t for the unruly wool puffs wafting about on the floor and webbing down from the rafters. This fiber would eventually be used for hardware-store paint rollers. Payne is always ready to drop everything to go to a factory in pursuit of a color or moment in the industrial process that he has been chasing.

Even when the product being manufactured isn’t colorful, hints of cobalt blue, sunny yellow, and fire-engine red pop up in Payne’s photographs, thanks to factories using these primary hues as warnings and decorative accents. He waited months to get the spaghetti strands of blue pastel at the General Pencil factory in Jersey City. Gloved hands gently hold the soft material atop a stack of wooden boards cut with ridges to shape the strands. The scene is rendered with Payne’s classically cinematic Rembrandt lighting evenly illuminating the hands while letting the background fall into darkness. There is an air of timelessness to the image. Payne says it is hypnotizing to watch someone do a repetitive motion. When he was in one of the textile mills, he spent the better part of a day making a portrait of a man doffing a large spool of wool roving (wool fiber that has been processed but not yet spun) because he wanted to catch the moment of peak elegance.

This is usually the aim when Payne is photographing workers. He will labor over a portrait with the same fierce attention to minute shifts in position and lighting that he brings to his still-life images, trusting that he will have a chance to remake a picture due to the repetitive nature of assembly-line and factory work. The task will be repeated. He wants to illuminate and celebrate the skills of the workers and to honor their craftsmanship. There is no excuse for not getting it right. A tour through the Steinway piano factory in 2002 started Payne on his mission to document industry in America. He was overwhelmed by the beauty and delicacy of the artisans’ work and found himself thinking about it for the next decade. He eventually gained privileged access to the factory and began what would become a three-year project to show how pianos are made. He found it to be a “very meditative place,” and says, “When I saw them bending the wood for the piano around the rim press, I said, ‘Oh my God, that is the first step in the creation of a concert grand that will eventually end up in performance halls around the world,’ and I almost cried.

This is when the wood is transformed into the unmistakable silhouette of the piano. Before that, it is just planks.”

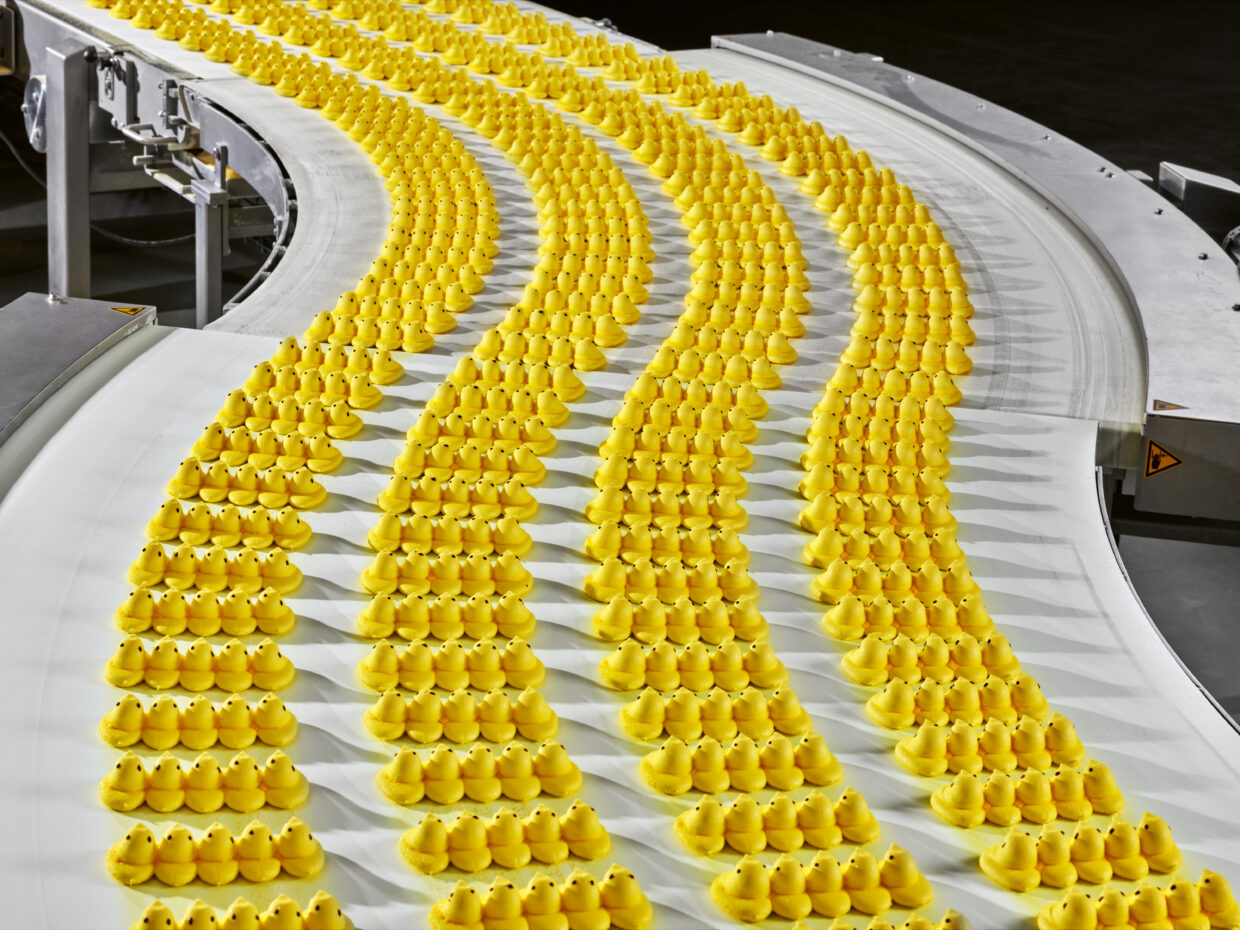

PEEPS Marshmallow Chicks cooling on a conveyor belt before packaging. Just Born Quality Confections, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

PEEPS Marshmallow Chicks cooling on a conveyor belt before packaging. Just Born Quality Confections, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

The smell of wood was everywhere. Much of the work is done by eye with chisel in hand. A “belly man” literally lies on top of the sound boards on a table cut out in the shape of a piano as he does his work. Payne’s grandmother and mother taught piano, and his father was a classical musician. He feels this has influenced his photographic work. He originally trained as an architect and worked as one for twelve years. When the Recession hit in 2008, he found himself at a cross- roads, realizing that he preferred being in actual physical spaces to drawing the plans for future buildings. He turned to photography full-time, crediting his years of translating three-dimensional spaces into two-dimensional drawings with giving him a deeper understanding of form and function.

The biggest challenge Payne faces is an unusual one for an artist. He is obsessed with process.

I first met Payne when Bonni Benrubi, his gallerist at the time, showed me his stunning photographs from the Steinway factory in the spring of 2012. We published those images in the New York Times Magazine, where I have been the director of photography since 1987. Since then, I have enjoyed working with Payne on numerous projects. We commission him because of his singular ability to make gloriously monumental photos that illuminate what he refers to as the “grandeur and sublimity” of industrial processes.

Three of the most memorable photo essays we’ve published—the textile mills, the pencil factory, and even the New York Times printing plant—were self-assigned art projects that Payne either brought to us after they were complete or asked us for help with to gain access to a facility; he had no promise of publication upon their completion. Payne, who sold newspapers in Boston when he was a teenager, desperately wanted to shoot inside the massive Times printing plant in College Point, Queens. After we granted him access, he visited the plant more than thirty times, often into the wee hours of the morning, to get the best images of the presses running and the press operators at work. Sometimes he came away empty- handed if things didn’t align visually in the way he hoped they would. This deep engagement with his personal projects gives him the granular knowledge of the manufacturing process he needs to make the formally beautiful and informationally meaningful images he seeks.

Warp yarns feeding a Jacquard loom for the weaving of velvet upholstery. MTL, Jessup, Pennsylvania

Warp yarns feeding a Jacquard loom for the weaving of velvet upholstery. MTL, Jessup, Pennsylvania

The biggest challenge Payne faces is an unusual one for an artist. He is obsessed with process. When he is photographing inside a factory, there is a constant inner tug-of-war between his desire to make the most beautiful photo possible and his desire to show how something works. He says, “I struggle with the burden to show process. To convey useful information as well as beauty. It can’t just be beauty. It has to have meaning.” It is a self-imposed burden. We published the photo essay of the Times printing plant as a special section of the broadsheet. A selection of the photographs he made now hangs in the Times building in Times Square.

Payne cites as influences the work of Andreas Feininger, the photographer who covered industry for Life magazine in the 1940s and 1950s; Alfred Palmer’s factory portraits during World War II for the Farm Security Administration; the industrial photographs of Ezra Stoller (who was known primarily for his architectural commissions); and the pictures Joseph Elliott made at the Bethlehem Steel plant in the 1990s. Payne has grabbed the baton and run with it. He shares the appreciation of sculptural forms evident in Bernd and Hilla Becher’s seminal documentation of disappearing industrial architecture in Germany, of objects such as cooling towers, gas tanks, and grain elevators. The big difference between their photography and Payne’s is that they clearly had a formal agenda and Payne’s is both formal and humanistic. Payne also looks to Vermeer’s paintings for his portraiture because, he says, “I love the soft side light and the way his pictures are architecturally composed and ordered, with everything in its place for a reason.” Payne’s work will one day resonate in the way Berenice Abbott’s Changing New York photos from the 1930s do today. They will serve as historic records.

To succeed, photographers need to be opinionated. Payne’s photographs declare with clarity and passion his belief that American manufacturing is to be treasured and valued and the workers respected and honored with our attention. The hard labor of these workers has been documented by one of the finest documentary artists of our time. This book should be the topping-out ceremony that occurs when the highest feature on a tall building is attached to celebrate the end of construction. After all the work Payne has done in magnificently rendering the toil of the workers and the beauty of industrial processes, he should be able to step back to survey the breadth of his achievement, but as I write this essay, I know he is still trying to gain access to places he hasn’t been able to get into yet—a jet engine test site, a high-tech pharmaceutical lab, and a space capsule he has been dreaming about. There is always something more to photograph.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Made in America: The Industrial Photography of Christopher Payne. Foreword by Kathy Ryan Copyright (c) 2023 Abrams Books. Used by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Kathy Ryan

Kathy Ryan is director of photography at the New York Times Magazine.