Captain Dynamite and the Exploding Coffin of Death: The Greatest Minor League Baseball Entertainment... Ever?

“Oh man, I think that sumbitch is actually dead!”

“Oh man, I think that sumbitch is actually dead!”

It was a hair-dryer-in-the-face-hot Sunday afternoon at McCormick Field, home of the Asheville Tourists of the South Atlantic League, the proud but not great Class A affiliate of the Colorado Rockies, the first full step of every ballplayer’s cleat-wearing march toward the big leagues.

On this day in 1994, amid a summer when those big leagues were constantly on the cusp of shutting down their season over money, McCormick Field was the perfect antidote for everyone’s MLB illness. It was everything that is right about baseball. A perfectly picturesque all-American throwback minor-league ballpark, just as it was when it was christened in 1924 and just as it still is today.

A grandstand packed with patrons, buzzed in the box seats on cold beer and peanuts, and none of it had cost them more than a few bucks. A baseball band-box carved into a Blue Ridge mountainside, laced with the unmistakable scent of western North Carolina honeysuckle blooms. A circle of gray concrete, green vines, and a kaleidoscope of advertising billboards, all wrapped around a diamond of a ballfield that for nearly a century has been tread upon by the Cooperstown-bound cleats of Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, and Willie Stargell, as well as thousands of minor leaguers whose names and unfulfilled big-league dreams have been lost to time.

In 1924, in the ballpark’s first official professional game, Cobb’s notoriously sharp cleats churned the dirt around McCormick Field’s second base, sprinting around the bag after he slapped a home run. In 1948, Jackie Robinson patrolled that same dirt, in town with the barnstorming Brooklyn Dodgers. Now, seventy summers after Cobb and nearly forty-six years to that exact day after Robinson’s visit, surrounded by minor leaguers of 1994, I was convinced that the very same spot of earth where the Georgia Peach and No. 42 had once roamed had just become a crime scene.

The shouter was right. Yes, that sumbitch really did look dead.

Looking back now, I am embarrassed at my surprise. After all, the man who lay motionless where the now-scorched infield dirt met the now-blown-back edge of the outfield grass was known as Captain Dynamite and his Exploding Coffin of Death.

I was a recent college graduate making $100 a week (cash) working in the Asheville Tourists’ front office. We had a summertime calendar packed with game day entertainers, everything from an Elvis impersonator (“Elvis Himselvis”) and a Blues Brothers–themed comedy act to appearances from Ronald McDonald and Billy Bird, the mascot of the Class AAA Louisville Redbirds. Billy was a much more affordable option than the most famous feathered mascot in all of sports, the San Diego Chicken.

Every performer commanded an appearance fee, covering an extremely wide financial scale. Most asked for several thousand dollars for one evening’s work at the ballyard. It was worth it. Every scheduled performance, whether it be a brand-name Chicken or a AAA Billy, brought an instant boost to that night’s ticket sales.

Captain Dynamite was 78 years of age but looked at least 30 years older than that.

But there were 71 home games in a Minor League Baseball season, and every team had only so much money to spend on pregame acts. In other words, not every night can feature Elvis Himselvis or the Blues Brothers. Sometimes you must book Captain Dynamite and his Exploding Coffin of Death. I believe his fee was $500 (also cash).

Among the endless tasks that can be found on the to-do list of a minor-league ball club’s young, fresh-legged $100 employees is aiding those game day entertainers, helping out with whatever they might need. That could mean lending a hand to carry equipment to the field or sneaking them a postshow six-pack from the beer cooler. When the good Captain rolled up to the ballpark in a well-rusted station wagon, he made it known that he required no such aid. In a superpolite, almost hushed tone, the overtanned fire hydrant of a man smiled and explained that he had brought his own road crew. He pointed to a hard-around-the-edges woman, a living Andrew Wyeth image that I assumed to be his wife, and a half-dozen unbathed children. I supposed they were his grandchildren.

Captain Dynamite was 78 years of age but looked at least 30 years older than that. Like redneck clockwork, the little Dynamites each grabbed a panel of foam board from the back of the Family Truckster and carried it through the stadium service entrance toward the playing field. There, they constructed a rudimentary rectangular box atop the dirt just behind second base.

Spoiler alert: The “Coffin” wasn’t a coffin at all. It was a home-made foam faux sarcophagus that had been painted black, but not well enough in a few spots to hide the “3M Insulation” logos. As for the “of Death” part of the setup, well, that looked pretty damn real. At least it certainly felt real as the Captain began carefully stuffing the box with old-school explosives, bright red sticks with long fuses that looked as if they had been stolen directly from the ACME stash of Wile E. Coyote. They even had “TNT” printed on them.

After packing the Coffin with the Death, our hero proceeded to pull a dark green jumpsuit over his jeans and dirty T-shirt, complete with well-worn all-caps “CAPTAIN DYNAMITE” embroidered across his back, along with the smoke-stained orange cloth image of an explosion. He then yanked a heavily scarred motorcycle helmet over his head, climbed into the foam board casket, and lay down among the explosives like a hillbilly Dracula as the lid was sealed above him. His crew shuffled down to the end of the wire, settling in alongside the first baseline, where Wile E.’s T-handled detonator machine was standing by.

I was watching all this unfold from the steps of the home dugout, only 150 feet or so from the coffin. I purposely stood a little lower than earth line, should that dugout suddenly need to become a fallout shelter. One by one, the Asheville Tourists ballplayers filled the space around me, mouths agape, as the countdown from the press box reverberated throughout McCormick Field and the surrounding neighborhood.

“Ten … nine … eight … seven …”

Anyone who had watched television over the previous few decades likely recognized the seat-rattling bass tone of the public-address announcer. Not the name but certainly the voice. It was broadcasting pioneer Sam Zurich, now a retiree living in the North Carolina mountains. For years he voiced promos and commercials for CBS television and local stations across the Carolinas. Sam had seen it all. He was the model of an unflappable broadcasting professional. But as he looked down from his press box perch to the coffin below, even Sam’s rock-solid tone carried a hint of “Exactly what in the world are we counting down to here?”

“Six … five … four …”

All 1,100 fans in attendance were on their feet. I felt a tap on my shoulder. It was Tourists righty pitcher John Thomson. He was on his way to a ten-year big-league career. But not yet. Today he was a twenty-year-old prospect half-jokingly handing out batting helmets to those of us in the dugout. “Just in case,” he explained in his Mississippi accent. “Some of that guy’s body parts might come flying in here.”

“Three … two … one …”

BOOM.

The concussion from the explosion was so forceful that the tiny ballpark could barely contain it. The ground was shaken with such power that a plastic cup from the box seats had been blown in from above, dropped from the hand of a temporarily incapacitated baseball fan, and splashed Pepsi all over the floor of the dugout. A flock of startled birds launched from the trees that towered behind the outfield fence. In the distance, car alarms could be heard from every parking lot around McCormick Field, whistles and chimes triggered by the blast. Everyone in the building reflexively raised their hands to their faces, covering their ears, eyes, or both.

Captain Dynamite’s crew shook him and screamed at him, all while the remnants of his Coffin of Death settled onto the infield around them.

When my eyes finally reopened and focused on the field, all I could see was a giant rising cloud of white smoke and falling debris of red infield dirt. That dirt was mixed with hundreds of pieces of black, silver, and pink foam, all dancing back to the ground like snow. The debris field was large. My initial reaction was, This is going to take forever to clean up. My second thought was formed as the smoke lifted and the Captain finally came into view, lying facedown in the dirt, not moving so much as one finger as the Family Dynamite scrambled toward him. I never spoke my reaction aloud. I didn’t have to. One of the ballplayers said it for me.

“Oh man, I think that sumbitch is actually dead!”

Prior to the performance we had been told that the Captain was in the middle of what amounted to his farewell tour. After four decades, several thousand explosions on everything from county fairgrounds to drag strips, and at least two arrests on charges of improper storage of explosives, Patrick O’Brien was grooming his replacement. Lady Dynamite was already making a simultaneous circuit of summertime ballpark stops, a much younger and much more spangly female version of the act, complete with an Evel Knievel–style cape covering her shoulders and a thong-anchored bodysuit of her own design that covered nothing. But right now, we were thinking that her predecessor’s farewell tour was over. Best we could tell, he had just said farewell to life.

Captain Dynamite’s crew shook him and screamed at him, all while the remnants of his Coffin of Death settled onto the infield around them. The weathered woman leaned into his helmeted face. I couldn’t tell if perhaps she’d stuck smelling salts under his nose or if maybe she had slapped him. Whatever she did, it worked. Captain Dynamite’s limbs stiffened, he sat up, and with the assistance of his family/crew, he rose to stand atop wobbly knees and waved to the audience, our jaws collectively unhinged.

Take that, Death.

My coworkers and I ran onto the field to start picking up the debris. I jogged by a stunned Captain Dynamite as he left the field, his arms draped over his companions’ shoulders for support as a small trail of blood trickled down one cheek. “Great job!” I said, giving him a thumbs-up. He looked at me and smiled wearily. Clearly, he had no idea what I’d just said. She barked into his ear, “He says you did a great job!” Captain Dynamite replied, but his hushed tone was long gone, his ears no doubt ringing like the bells of St. Paul’s.

“THANK YOU VERY MUCH!”

I think he tried to wink at me, but that’s when I realized that one of his eyes was glass. I also think he tried to give me a return thumbs-up, but that’s when I discovered that he was two fingers short of a full set. Scooting along behind the couple was one of the children, a boy of perhaps seven years of age, who looked me right in the eye as he dragged a roll of wire behind him and said, “My daddy done blowed himself up.”

As the Dynamites loaded back into their station wagon with the Captain’s five hundred bucks, we hurriedly ran off the field, dragging trash bags that we had just stuffed with a thousand Coffin of Death remnants. As we stepped off the diamond, the home-team Asheville Tourists, in their sparkling pinstriped home whites, trotted by us to take up their positions and take on the Hickory Crawdads. Another shout echoed throughout McCormick Field. It came from behind home plate.

“Play ball!”

__________________________________

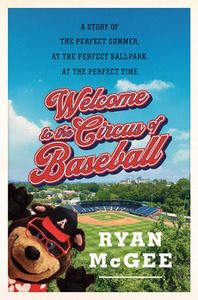

From Welcome to the Circus of Baseball: A Story of the Perfect Summer at the Perfect Ballpark at the Perfect Time by Ryan McGee. Reprinted by permission of Doubleday, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright (c) 2023 by Ryan McGee.

Ryan McGee

RYAN MCGEE is a senior writer for ESPN and cohost of 'Marty & McGee' on ESPN radio and the SEC network. He has won five Sports Emmys, including two for his scriptwriting and feature work on College GameDay. McGee has authored several books, including cowriting the New York Times bestseller, Racing to the Finish, with NASCAR superstar Dale Earnhardt Jr. He also works as a field reporter for ESPN’s SportsCenter, and as a feature reporter for E:60. McGee lives in North Carolina with his family