Candy Wilson had forgotten to buy the paprika. She had thought about it more than once that morning in town as she pushed her cart down shiny aisle after shiny aisle at the Marsh. Now it was clear to her that this thinking—this seeing of her hand scooping up the little red and white paprika tin, the way it actually scooped up eggs and orange Jell-O and pineapple and carrots and real butter and a fresh jar of Hellmann’s and every single other thing on her list—had taken the place of getting it done. Meaning she had a problem. Club was set to start in just a few hours. Some of the members liked her pigs in a blanket, some her caramel corn, and Alma Dunn and Lois Burton always took seconds and sometimes even thirds of her sunshine salad, but to a rosy-red carapace every member of the Bright Creek Girls Gaming Club loved her deviled eggs. Paprika was the recipe’s sine qua non, and Candy, whose turn it was, couldn’t host the monthly meeting without it.

She had the eggs ready to roll. They were boiled and peeled and halved and scooped and laid out cool and white on Saran Wrap-covered trays. The vinegar was measured, and both the mustard and the Hellmann’s needed only to be opened and dolloped out. Candy loved to dollop. It was one of those small things that made the big things better. First there was the weight of the whipped cream or the mashed potatoes or the cookie batter or the mayonnaise or, in the case of deviled eggs, the creamy yellow mixture the mayonnaise had brought into being. Then there was the turning of the spoon and the quick downward motion that you stopped almost at the same time you started it. So satisfying. It made Candy grin. It pleased her soul. And it didn’t hurt that you sometimes had to help whatever it was you were dolloping to find its way off the spoon. For then the helping finger could be licked.

In the meantime she was nonplussed. Town was twelve miles each way. She liked driving and often made up reasons to jump in the car and go off plenty farther than Frankfort, but the clock wasn’t on her side. She picked up the phone and called Alma, and Alma said try Laetitia, and Laetitia said try Zorrie, and she did but Zorrie didn’t answer her phone. This was not surprising. Zorrie was still always out of doors. She was out of doors as much as many of them were indoors. Candy wondered if she ought to drive over. Probably Zorrie was out in her garden or mowing. She did a lot more of that these days than she had ever used to. Even if she didn’t have any paprika they could visit for a minute. A minute couldn’t hurt. Zorrie wouldn’t care one bit that the paprika was for deviled eggs for a meeting of a club she was not, by choice, a member of. Candy got her keys and purse.

It was mid-July. But not too hot. A storm the night before had cooled things down. Candy drove with her arm out the window of her Buick, and if her shoulder hadn’t hurt, she would have turned her hand into a hawk and let it rise and drop. Just about everyone who still earned a living on a tractor was out doing something. The sky was blue. Zorrie Underwood’s acres shone bright and green and her lawn looked better than respectable. There was a garden of note peeping out from behind the barn. Candy’s own garden had for years been a pitiful thing. She called it her abomination. She liked to tell people about how badly it was coming. She used the word abomination as often as she could. As she climbed out of the car, she saw something move and thought Zorrie’s old dog, Oats, was about to come tearing around the house to holler at her, but it was just a cat. Oats of course was long gone. Candy knocked on the door but there was no answer. She sat a while on Zorrie’s back steps. She could see the green roof of the Summers’ house through the trees. The idea of asking old Noah Summers if he had any paprika made her chuckle. “Still, I am more nonplussed now than I was a while ago,” she said to a sugary gray catbird that was pecking around near Zorrie’s pillowy hydrangeas. She pulled a sticky note out of her purse, scribbled on it that she had come by to borrow paprika, stuck it on Zorrie’s screen door, got back in her car, and headed for town.

Nonplussed had been a word favored by Candy’s great friend Irma Ray. Irma had known all the words. For a stretch she had taught French over at the high school, where for many years Candy had served as a substitute teacher in Home Ec. Unlike some of the others who had liked to make weapons out of strings of letters just so they could smack you upside the head with them, Irma had always deployed her vocabulary for the good. Too many to count were the times Irma had sat in Candy’s kitchen and watched Candy at her dolloping and, just by the way she said something, helped Candy to think more clearly about whatever issue had vultured down on her day. After Irma had stopped teaching and started tutoring out of her house, she and Candy had become even closer. Irma’s skill with words had not made her popular with the girls in the club, and she had attended only once as Candy’s special guest. Still, she was the one who had suggested Candy always splurge on Hellmann’s for her deviled eggs and that she use butter instead of Crisco for her cozy little pigs. Who said you couldn’t teach an old Home Ec teacher new tricks? Following Irma’s advice had made all the difference. Club at Candy’s house was considered something you could not miss. It was the apex of the yearly club calendar. Irma would have had paprika on hand. Her headstone had been standing over at Bright Creek’s Bakerworth cemetery for a year now.

The Marsh was busier than Candy liked when she had an errand to execute, and of course, since she was in a hurry, she saw about one hundred people she knew. She had been a popular substitute teacher and for a while a fixture at Elks events across the county with her took-off husband, Frank. She might well have been retired from teaching, but she still couldn’t come into town without getting struck up by familiar faces. Today, it was like bugs on a windshield, the big splattery kind. First there was a family of Newtons and then another of Thompsons. The Thompsons had a new baby in their number, so Candy couldn’t just wave and keep on. The baby was asleep, so the visiting was conducted at a whisper, lest the little banshee awake. There was something to say about someone’s aunt’s surgery. Also, the mother of the baby wanted to show that she still had her hospital bracelet on. She said she was going to wear it until little Deirdre’s first tooth came in. Ordinarily it was Candy who kept the bellows blowing on a conversation, but the clock was ticking so she made her excuses, bent and cooed over baby Deirdre, and then pressed on. Earl Crick, who had been in the Elks with Frank, slowed her up in Floral long enough for her to decide to put a bouquet of yellow roses in her basket. Earl’s wife, Selah, had made a presentation at church about keeping a spiritual diary a few weeks before. Thinking about keeping a spiritual diary made Candy laugh. What would be the point of it? What would she write? She hadn’t ever seen anyone walking on water. She hadn’t seen any burning bush. What she could see, through the window, was her cousin’s great-nephew, Tod Henry, chasing carts in the parking lot. At some point he’d grown handsome. Or almost. It sometimes happened. She wondered if he’d developed good manners to go with the cheekbones and shoulders. The little white-topped red tin of Durkee paprika looked pretty next to the roses. Beryl Reedy was at the register, and because it was clear that she was working up something to say about the flowers to do with one of her soap operas that was way more complicated than it had to be and would take a while to get said, Candy cut her off. “Club day. I forgot the paprika. We got bingo going this month.”

Bingo was actually Razzle Dazzle, and it was everyone’s favorite. They all got dressed up like they made their living in a gambling hall and put on visors, and some of them, Candy included, even wore pink or purple eyeglasses. Each girl had her own marbles and made a fuss about them. Lois had the nicest ones. She’d brought them back from a trip to see her niece who ran a cake shop down in Louisville. The club’s newest member, Gladys Bacon, had marbles filled with glitter. The marbles were just cheap glass but the glitter was all different colors. She kept them in a red and yellow silk bag they’d given out at the Panda House buffet one Christmas. You couldn’t put up less than a quarter. In all their other games the minimum was a penny. They used a score chart that made it easier to win, but you still had to work at it. Cheating was tolerated though not openly encouraged. Some of the girls took it more seriously than was strictly necessary. That happened sometimes when they played their euchre tournaments too. Candy was a hand-straight-up-in-the-air offender when it came to cards. Win or lose, she always slapped her play down too hard. Razzle Dazzle mostly just made her laugh. She especially liked the sound of the marbles as they hit the board and rolled around crazy until they found their holes.

At the one club meeting Irma Ray had come to, Razzle Dazzle had been on the menu. Candy had put a spare visor on Irma’s head and the two of them had played Candy’s marbles. Afterward, as she had helped clean up, Irma had voiced her admiration both for the game’s “bizarreries” and for the club members’ bawdy-house costumes. Candy, maybe too eager to broach the subject of possible membership for Irma, had repeated Irma’s observations at the start of the next meeting. Irma had said she thought the debauched court of King Louis the Fourteenth at Versailles would have liked Razzle Dazzle, and Candy, though she immediately thought better of it afterward, especially of including the word debauched, reported this too. The reaction of the girls was not what Candy had been hoping for. It was clear that there had been prior discussion among them. Alma summed it up nice and neat by saying maybe there ought to be a limit on special guests coming to club. That maybe once was plenty. Others nodded. Some looked away. There was a good deal of slurping and loud chewing. Candy shut the subject down with a sharp, “Well she doesn’t want to come back anyway.”

Which hadn’t been anything but the truth. Even if she had gotten the girls to go along with it, Candy had been sure that Irma—whose tastes in entertainment ran in different directions—would not have accepted. But Candy had wanted to be able to put it to her. Irma would have appreciated that. Candy had pulled out of the Marsh with the intention of getting home as quickly as possible to dollop and mix, then dollop again and sprinkle, but almost as if they had started making their own decisions while she got grumpy, Candy found her foot pumping the brakes and then her hands turning the steering wheel so that she could cut over off 28 to the Kelly Road. By itself, this wouldn’t have been much of a detour, except that when she had slid east along its smooth blacktop past the Red Barn Theater, where she and Irma had taken in many a show, she turned right instead of left onto 421 and rolled south to Bright Creek and then, after honking at Turner Davis, who was working a hoe in his front flower bed on North Main, west out to the Bakerworth cemetery so that, on this anniversary of Irma’s quiet funeral—which had been attended only by Candy, Zorrie, Hank Dunn, Toby Slocum, and two or three at the most others—she could pay a quick tribute.

One of the yellow roses came out of the car with her. When she was halfway across the grass, she stopped, turned, went back to the car, and fetched up the rest of them too. Irma had always been partial to cut flowers, and you about hadn’t been able to step into her house without smelling lilies, peonies, or roses. Yellow in any shade had without question been her favorite color. Irma hadn’t lived particularly close to the Bakerworth cemetery and might more logically have chosen Beech Hill, but she had always favored Bakerworth. Said she liked the way the countryside rolled out clear in all directions. Said a cemetery ought to have some view. Candy could remember the day when Irma had announced the purchase of her plot. It hadn’t been very long before they had lowered her box into it. She’d always had money. Single woman with a job. Her tutoring work wasn’t much, but she still had money in the bank and had owned her house outright. It was why she had been able to go off on trips. Candy hadn’t gone with her on any of those. They never even ventured outside the county together. Candy had postcards from Miami, New Orleans, and San Francisco. Though Irma had been to Paris and Rome in her youth, the farthest she got during the years Candy knew her was up in Canada. She brought Candy back a stuffed grizzly bear from that trip. It had a ribbon around its neck that read “Dawson City.” Candy kept it on a shelf in her bedroom.

The cemetery had a healthy look. The daylilies were up in force, and there were sweat bees hanging easy in the air. The grass had been mowed recently enough that it tickled her nose, and there were bright green trimmings even up on the top of Irma’s headstone. Candy swept them off with the back of her hand. The smooth, black stone was warm. Letting her hand lie there a minute, she closed her eyes and hummed a little. It was something she did when she visited Irma’s grave. She did it instead of talking or praying. Well, she sometimes prayed a little too: for Irma’s easy passage, her safe departure, the heap of fresh adventures she had ahead of her now. You had to think God would be helping out. Candy had gone so far as to ask the reverend one Sunday after church if he thought God showered his favor on people who were different. “Different how?” the reverend had asked. Different how indeed? Irma had had the Latin phrase “Astra Inclinant Sed Non Obligant” engraved on her stone.

Candy put the radio on for the drive home. It was a pop station out of Lafayette. Generally she liked whatever was on. Unlike Lois and Alma who turned up their noses, she thought what got played these days was better than most of the old chestnuts. She had never been able to stand Elvis Presley even though plenty of them still got moony-faced whenever “Hound Dog” or “Love Me Tender” came on. She had left the flowers standing against Irma’s grave. She knew they would fall over the first time the wind cleared its throat, but for now they were standing tall and would keep standing for a little while and that was about all you could hope for. Next time she would bring a vase. She kept meaning to. Irma deserved that. She deserved a hundred vases. Candy hoped that’s just what she had, a hundred flower-filled vases, wherever she was. Somehow or other, before Candy left, her hand had again followed its own orders and reached into her purse and pulled out the tin of paprika to set atop the warm black stone. She thought she would just leave it there a minute, but it looked so nice with the yellow of the roses and the black of the stone and the green of the fresh-cut grass that after she hummed some more she walked away without taking it with her. She would put pepper on the eggs. Maybe add some cayenne. Let the girls Razzle Dazzle that down. What was wrong with being different? It was exactly what Frank had called her plenty of times and she’d done all right. He called her that the night they had fought for the last time and she told him that if he slapped her just once more she would put an axe between his eyes as he slept. She grabbed up the Bible and took an oath about it. Frank slapped her exactly once more and then got in his car and never came back.

Candy looked right, then left, when she got to Bright Creek. If she turned right, she could roll straight to Indianapolis. She had always thought one day she would drive down there. See for herself who it was Irma had kept running down to visit. They never once talked about it, but Candy knew the address. She had carried Irma’s mail up to the house from the box at the road more than once on her visits. The envelopes were turquoise. Irma had burned all the letters before taking her leave and a breeze must have come up because there were bits of burnt turquoise caught in Irma’s hollyhocks and dahlias. Candy plucked one of these from a crimson bloom and kept it for good luck. Turner, who had been seeing to his zinnias, was no longer in his yard. Candy liked a nice zinnia but Irma had not. She said they had funny connotations for her. The girls would be arriving in an hour. Candy was cutting it close. They would all be on time. It was not the kind of club where anyone ever arrived late.

Irma had rarely been on time. In fact, she had been late even the day she pulled up in her nifty yellow Chevy Nova coupe as a special guest to play Razzle Dazzle and eat refreshments with the club. Candy had liked this about her. Most people said she was standoffish and not much fun, but she hadn’t been either of those things, not when you got to know her. When you got to know her, you could never tell what she would say or do. Things had not been easy for Irma at the high school. The vice principal had taken her aside any number of times. It was the principal, not the vice principal, though, who asked Irma to step into his office not long after the rumors started to run. And it was the principal, after someone had seen Irma and her coupe down in Indianapolis, who told her she had better gather up her things.

Candy had gone straight over to see Irma when she heard. There was a Billie Holiday record on the player, and Irma was sitting close to the speaker, swirling a glass of wine. “Got an idea,” she told Candy. The back seat of the Nova was covered with rolls of toilet paper. It was game night in basketball season, so everyone was over watching the orange ball go bouncing up and down the court at the high school. The principal had persimmons, crab apples, and pear trees that lent themselves especially well to the exercise. Candy wasn’t much of a hand at throwing, but Irma could really heave. They made the vice principal’s ranch house, garage, and gazebo their primary targets at the next stop. Irma dedicated each roll to a different insult she’d received from him: short skirt; see-through blouse; sour expression; sick, sick, sick ideas. When they got back to Irma’s, Candy, who never drank, allowed herself a splash of wine. Irma, meanwhile, polished off the bottle. And after a few glasses her mood shifted. She said some things in French that didn’t sound good. When she switched back to English, she told Candy that the principal had probably been right to fire her. She had dressed improperly, she had spoken inappropriately, she had taught racy novels, and she had—oh yes she had—misbehaved. Candy shushed her, made her something to eat that she wouldn’t touch and then put her to bed. As Candy was leaving, Irma said in a small voice that the person she went down once each month to see in Indianapolis wasn’t even nice to her, and she didn’t know why she hadn’t been able to quit going there. Candy said what Irma did was her own business and she didn’t have to explain anything. Irma responded that she had often wished it was Candy, not that unkind person, who lived in the little blue house behind the high bushes at the end of the street in Indianapolis.

Candy had never lived anywhere in her adult life but in the house she had inherited from her parents. It was a nice place. Even Frank had always said so. He had never minded living there, especially since there hadn’t been any rent or mortgage to pay. As she pulled into the driveway, she looked upon the neat lines and tidy white paint and clean windows and sturdy roof and respectable flower beds. It was true that her lawn needed the mowing that she now wouldn’t have time to give it and of course there was the abomination out back, but you couldn’t get everything done. Everything wasn’t possible. Everything wasn’t even anything she had ever wanted. For a long time, she’d raised chickens but they had finally worn her out, so she had let her band of merry seed snackers go. Sometimes she missed the birds themselves but not the waking up early to tend them. Still, they had kept her somewhat in shape. Irma had often said she, too, ought to have chickens, that she appreciated how having them made a person stir around. There had been the smell though. Candy and Irma had laughed about it, but on a hot day it had filled the house. Candy was glad that the girls arriving soon wouldn’t have to contend with that.

The time for raising chickens had passed, but Candy knew she was going to have to do something to get herself into shape. Her back and left shoulder hurt worse than usual and she was short on breath from her errand, and the push to get ready for the meeting kept making her want to sit down. She had a doctor who said every time she went in to get her blood pressure checked that she needed to lose twenty pounds. It was always twenty even when she had gained some. If she had had time, she would have drawn a bath and then taken a quick nap. But she did not have time. And now she felt foolish for leaving the paprika behind. Like anyone else she could be a little sharp sometimes, but she did not like to think of herself as spiteful. She would just put a little salt on the eggs. There wasn’t any call for cayenne pepper. It wasn’t like any of the girls had ever been flat-out mean about Irma Ray. Sometimes some of them had even asked after her. When they had all seen one another at the Red Barn or at the cinema in Frankfort or at the Jim Dandy or Ponderosa, it had always been cordial. Everyone had particular friends. Everyone ran around. After word of Irma’s death got out, a few of them—though none of them had attended the funeral—had called Candy up to express their condolences. Lois had said how sorry she was that Irma had felt badly enough that she needed to do it.

Candy dolloped and mixed, then scooped and dolloped. Thinking about those twenty pounds and all she was going to allow herself in the coming hours, she waited to lick her finger until every last egg had been filled. How many devils would she eat? She’d get her share. She was about to start sprinkling the salt when she heard a knock on the front screen. She took a bet with herself that it was Myrtle Kelly. Myrtle was famous for her loud laugh and for always wanting to be the first person at the parade. Or it might be Gladys. Gladys liked to arrive early just in case she needed to leave early, which she almost always did. Probably it was both of them, since they often rode together. “It’s open!” Candy hollered. When neither Myrtle nor Gladys nor anyone else came in though, she wiped her hands, took off her apron, and, still certain it was someone with a cup and marbles in her hand, picked up her visor and pulled her little purple sunglasses on. But when she tugged open the door, she saw Zorrie Underwood, cast in purple, pulling away in her truck. On Candy’s front steps sat a tin of paprika with a note under it that read, “Had it for a while but there ought to be enough dynamite left in here to get the job done.”

Zorrie, Zorrie, Zorrie. Always there. Never any fuss. Didn’t matter if you wanted to borrow milk or paprika or had some acres you needed plowed. Candy would save her an egg. Maybe she would save out two. That way Zorrie could give one of them to Noah Summers. Zorrie was in love with Noah. Everyone knew it. Life was funny like that. All those little secrets that weren’t secrets at all. Moving quickly but carefully, Candy opened the tin and tapped her way down the rows. She didn’t like to scatter the paprika too freely. She wasn’t throwing rice at a wedding or tossing confetti around. There was a way to do it even when you only had about a minute before people started banging on your door. That was something she had talked about in her classes. She could have been the regular teacher. Everyone always said so. The same vice principal who had taken Irma aside had even mentioned it, but then he asked Candy out and she turned him down and that was the end of that. She and Irma laughed about it later. It even came up one of the last times they saw each other. It was the evening that Irma put a record on and, when a slow song started to play, held out a hand and asked Candy if, well, she would care to dance. Candy had said yes, yes by God she would care to dance, and they had gone turning close and slow around the room. At one point during that dance Irma leaned in and whispered what she referred to as an additional request, and after they took another turn across the soft carpet Candy again said yes. She said yes, yes of course, and then they both laughed about it, and the evening carried on and they saw each other a couple more times, and then, according to the inquest, Irma hanged herself in the shed. Hank Dunn was the one to find her. Nobody thought that was strange. They’d been friendly for a long time. Candy worked with Hank to make sure Irma’s wishes were respected: simple funeral, no viewing, coffin closed.

Candy finished tapping out the paprika and licked her finger. She’d got the mixture right. Warm and smoky. Almost sweet. She took two deviled eggs off the tray, wrapped them in plastic, and put them in the fridge. Standing there with the cool pouring out and the two eggs tinted purple, Candy smiled, smiled about her great friend Irma Ray, off on her next journey, though after a minute she found herself wishing so hard her head began to hurt that she still had reason to set aside a third. That evening, when the girls finally grew tired of marbles and quarters and cheating, and Laetitia suggested, without in any real way meaning it, that they put on some music and cut a rug, Candy almost leaped out of her seat to switch on the radio. The song that was playing pleased no one. Not even Candy. Still, after everyone had gone home, and she had taken off her visor and glasses and cleared away everything she had the strength to, and was thinking about the bath she’d wanted earlier, and about the sweet, soft mercies of her bed, she tried the radio again.

She got it on just in time to hear the final few notes of what must have been a very pretty song. And then there was a silence. And then the fine, deep voice of an announcer rumbled in like last night’s storm. The voice reminded Candy a little of her father’s. Her father had liked to carry her on his shoulders. He had liked to swing her around. He would swing Candy around and around, and when he let her go, she would lie there laughing on the grass. The world spun and Candy couldn’t stop laughing. Sometimes when she visited Irma’s grave, when she was done humming, she laughed. She had done it again today. As she went back to the car. She had turned around then and winked at the stone, at the flowers, at the bright little paprika can and the blue of the sky beyond. According to Laetitia, Candy had outdone herself with the deviled eggs, they were the best ever “The best ever,” Candy said to the empty room. She switched off the radio. She went upstairs. “Now how about that?” her father had always said.

__________________________________

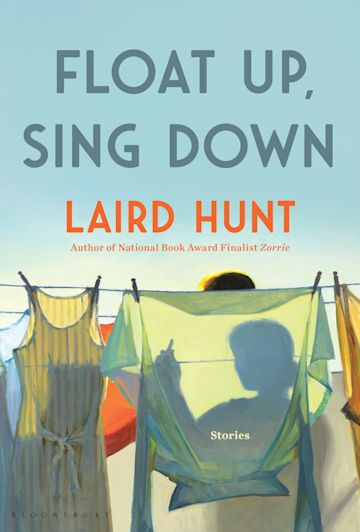

The story “Candy” from Float Up, Sing Down by Laird Hunt. Used with permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury. Copyright © 2024 by Laird Hunt.