Can You Fail at Sisterhood?

No One Understands Sophie MacKintosh Quite Like Her Sister

Me and my sister had our own language as children. I was an inventor of language—of elaborate code in my childhood diaries, rune-like and incomprehensible, and of big words, as many as you could fit into a sentence. But this language, it was between us. I do not remember this language we shared, only that it existed.

Now she talks fluidly and confidently, but my sister didn’t speak properly until she was five years old, and I can’t help but feel partly responsible. When she was asked a question she would defer to me, and I would answer. My mother’s favorite story is the time she was taken to a speech therapist and refused to talk or respond until the end, when she looked our mother wearily in the eye and asked “Please can we go home now?” (I identify.)

My sister is getting married in one week. Our communication for the last year has been mostly through WhatsApp, through emojis and gifs and screenshots of bridal makeup. She lives in Australia and I in the UK, our timezones rarely overlapping. She has lived far away from me for years now. Where I settled in London and didn’t budge, she moves adventurously, lightly, through the world.

In the months before her wedding I found comfort in sisterhood, returning to the books I have loved. I read My Puny Sorrows by Miriam Toews again and again, affected each time. I re-read The Virgin Suicides, remembered the teenage art project where I cast her and her best friend as two of the sisters, took polaroids and posed them with crucifixes and school uniforms. I re-read Little Women and try to figure out which ones we are. She is Amy, I decide, but kinder, like maybe a mix of Amy and Beth? And maybe I am Jo? Fictional sisters, frozen in time.

Or maybe we are none of them. Maybe we are just ourselves, two very different women who have the same laugh, the same blood. Maybe I don’t need to place or find context or precedent for our sisterhood, because it is a dynamic and changing thing, because I can give voice to it myself.

We have another shared language, one that’s lasted into adulthood—we speak Welsh, were educated in it our whole lives. My parents don’t speak it, so it’s ours. As well as Welsh she speaks fluent Spanish and works as an English teacher. Being good at language is common in those raised bilingual, as if the leap of thinking things two ways is the hardest part. Why not three ways, four, five?

So you can see then that my experience of sisterhood has always been tied to language; to secrecy and fluency, to in-jokes, verbal and non-verbal. Yet I find expressing myself difficult, other than through writing. I do not pick up cues that come naturally to other people, and I mumble, stumble, forget normal things to say. Maybe I turned to writing because there I can achieve a clarity that I can’t when talking in real-time. It is only with my sister that I do not stumble. Brutal honesty. The correct word, there, on my tongue, as if by magic.

She is so far away from me normally, and the proposal moved her further. I think of us as two pieces on a chessboard, the chessboard is adulthood, and I keep making lateral moves but she is making the moves forward. Moving in, getting married. I want to skip ahead and get to the ones like have a baby but she will probably get there first, though she is younger than me. My feelings on this are complicated, but then sisterhood feelings so often are.

It’s easy to get too gummily sentimental about siblings. You don’t have to love your family members.

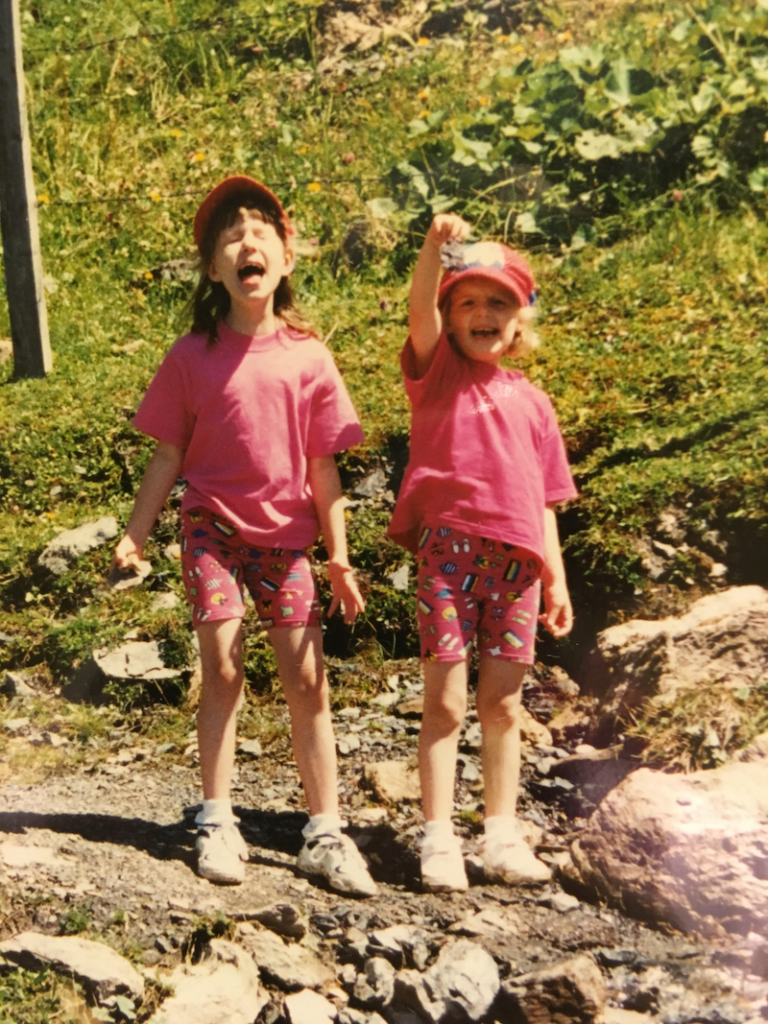

The age gap between us is about the same age gap as the two eldest daughters in my novel, 18 months, which is not so much at all. In many ways, it is too close. At one point we were in the same school year. Our friendship groups were different; she and her friends went to Young Farmers Club rallies and drank sugary vodka mixers in miniskirts, while I wore all black and wrote bad, anguished poetry. We passed in the corridors without smiling.

It’s easy to get too gummily sentimental about siblings. You don’t have to love your family members. Sometimes love can be destructive too, can tie you to people and concepts you should cut loose, because you are supposed to forgive everything. There were times when me and my sister would say that we hated each other, when we were strangers to each other.

But still: she had a major operation when the was 17 and I was 18. My parents pulled me out of school one afternoon following her surgery and drove us, grim-faced and too fast, down the motorway, and I cried secretly so they couldn’t see. And the morning after a very bad thing happened to me, when she was home and recovering, still giddy with morphine, it was into her bed that I curled. Hot and raw from the shower, I held her hand and tried to breathe.

Things were a different complicated when we were younger. I think about the time, as a six-year-old, I hatched a murder plot in her honor, deciding the kill the bully who was tormenting her every break time. I was six. Me and my friends streamed across the playground when the murder scheme (an orange soaked in bubble bath) failed. I held her tender wrists in my hands and I pulled her to freedom. I felt the compulsion to protect her that has never left me. Baby bird.

There were times during the writing of my novel, so many years later, that I thought: sisterhood has failed me! And I also thought sometimes, darkly, I have failed at sisterhood.

Writing my novel was a grappling with sisterhood immediate and larger; it felt right to dedicate the book to her. Now I’m writing this essay instead of writing her wedding speech, because to write the speech is too strange, too much. I wrestle with it, and wrestle, hoping for the moment of: there you are.

My sisters’s husband-to-be doesn’t understand our in-jokes, or the way we sprinkle Welsh or nonsense words through our speech when we talk to each other. There are obscure references that have been smoothed down like pebbles into our language. I have this with my partner too, and my oldest friends. I love these linguistic topographies, the uncanniness of language tweaked, remade. Language loved into something else.

But I do not understand the new language she speaks in, of table arrangements and gift registries and family-starting. In some way she has shot ahead of me, my younger sister, has a currency I don’t. I can make language bend to me (to a degree), but I still work in a world of theoretical, of the invented. There is something very concrete about marriage, though it too is just made up of words and a piece of paper.

Which sister am I? my sister asked, when she read my novel for the first time. Which one are you? But it depends on which day you are asking, on the time I was writing it. I came in as one sister and went out another.

Instead of writing the speech, I read My Sister the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithewaite, in which a sister sorts out the murder scenes of her younger sister. I read Empire of Sand by Natasha Suri, in which the daughter of a noblewoman is kept apart from her sister, is not allowed to comfort her, makes a sacrifice for her safety. I read the short story “The Toast” by Rebecca Curtis, in which our picture of the eldest sister shifts, devastatingly, throughout. There is so much complexity, so much depth, in these relationships. In the push and the pull of what it means to be a sister.

It’s the day of the wedding and the other bridesmaids are late for hair and makeup. After mine is done I sneak off through the day to finish writing the speech. I decide against edgy anecdote and bad jokes, and move in favor of love, of embracing sentimentality. I write about her happiness, her joyfulness, the way she lights up a room. When I read out the speech at the wedding itself, the words come out right. There is no hint of the stammer that has plagued me through book events over the past year, no blushing or shaking. Speaking about my sister and how much I love her, even to a whole room, gives me strength.

We might grow apart, but we always come back. We may never recover our first strange language, we may forget the words of our other shared ones, but there are new languages to learn and speak together, new parts of our lives together and apart to be discovered.