Can Friendship Transcend Death? On Missing Your Best Friend

Christie Tate on the Friend Who Taught Her “How One Life Can Alter Another”

When it was my turn to speak, I squeezed the pink heart-shaped rock with my left hand and grabbed my notes with my right. If you looked closely, you’d see my whole body slightly shaking. Halfway up the stairs to the stage, I lost my shoe and had to backtrack to retrieve it.

Slow down. Breathe.

This was my first eulogy. I wanted to honor my friend Meredith—the first friend I’d ever lost like this. To death, that is. I’d lost plenty of friends by other means. During my four-plus decades of life, I’d been in friendships that blew up or dissolved in both inevitable and unexpected ways. I’d withdrawn, drifted away, lost touch; I’d also ghosted and, more than once, watched seemingly close friends vaporize before my eyes. It was a miracle that Meredith and I enjoyed an uninterrupted run of close friendship for more than a decade.

My eulogy could best be described as a collage. A Meredith collage. I’d culled lines from over 1,300 emails she’d sent me over the years. Each snippet highlighted a specific role Meredith played in her life. Most of us gathered in this multipurpose room of the Ebenezer Lutheran Church on Chicago’s North Side knew Meredith as a pillar of recovery in twelve-step meetings, because she attended roughly one zillion meetings in church basements, elementary school classrooms, and hospital atria during her too-short life. But she was also a striving graduate student, an earnest wife, a jealous sister, spiritual seeker, an exhausted employee, a faithful daughter, and an anxious friend. She, like all of us, contained multitudes, and I arranged her words to celebrate her in all of her complicated realness.

From the stage, I gripped the microphone in the hand that held the heart rock Meredith had given me months earlier, the day before one of her scary scans. Since her death, I’d carried it with me everywhere. I’d read that quartz not only enhanced spiritual growth and wisdom but also clarified thought processes and emotions—all of which I needed now more than ever as I stood in front of a hundred people memorializing the life of our friend.

As I spoke the first few lines, my voice echoed off the stained-glass windows and bounced back to me sounding tentative, shaky. I took a quick pause to center myself, and then read Meredith’s thoughts on her lifelong struggle with loneliness in friendships. Several of the women in the audience chuckled. They knew. Friendship is hard. For many of us, friendship has been almost as tricky to navigate as romance. In some ways, more so.

A minute or two into my speech, my muscles relaxed, and my shoulders sank back into my body. My hands steadied, my voice stabilized. I slid into a good rhythm. Every few lines, I made eye contact with audience members as I’d learned in high school speech class. When I looked up, I met the gazes of women in the audience. Their smiles beamed love and tenderness toward me, and I received it. Another miracle.

It was with Meredith’s help that I’d learned how to be a friend. A bona fide, true-blue, long-term, steady friend. Through her, I learned to tolerate the vagaries of friendship, address the pain of competition with and envy of other women, and confront the lie of my own unworthiness. Without the work I’d done with Meredith, I would have looked out into the audience and seen threats, competition, and frenemies. But as I spoke Meredith’s words out loud, I saw loving allies. I felt suffused with tenderness, even for those women over whom my inner demons of envy, resentment, bitterness, and scarcity had taken me to very dark places. Standing on that stage, I could feel it: I’d changed.

After I read the last line, I made my way back to my seat, relieved to be done with the public-speaking portion of my mourning. Through the remaining speeches and songs, I sat squarely inside the bull’s-eye of grief, running my fingers over the cool surface of the rock in my palm. I missed Meredith. Every day, I craved conversation with her. I longed to text her about everything: my new meditation app, whether my dress made my breasts look lumpy, Adele lyrics, complaints about my husband, a question about what to get my dad for his birthday, a recipe for no-bake cookies. I felt bereft and understood that I would for a long, long time.

But there was also the faint drumbeat of anxiety. Sure, I felt bighearted and magnanimous toward every female soul at Meredith’s memorial service, but what about in the weeks and months to come? Would I revert to my old ways? Slip into the version of Christie who ghosts when conflicts and tension arise? Without the scaffolding of Meredith’s presence, could I remain the steady, solid friend she’d encouraged me to become in all my friendships?

Not so long ago, Meredith and I both believed that we simply weren’t cut out for go-the-distance friendships with women. We joked that we were too damaged by our history of addiction, too twisted by our petty jealousies, and too wounded from growing up alongside golden sisters with luminous hair, radiant complexions, and all-around upright lives.

But we decided—actually it was her idea and I went along with it—to focus on friendships. “Let’s do the work to get better at them,” she said, her cobalt-blue eyes boring directly into mine. We excavated our pasts and appraised where we’d done wrong by our friends and where we’d been led astray by toxic ideas that no longer served us. We did it in conversations over breakfast sandwiches, on coffee dates, on walks down the sidewalk after twelve-step meetings, and over the phone.

What happened was simple: we changed.

*

About ten months before she died, Meredith called me early on a Saturday morning when I was out walking in my neighborhood. That fall morning, the sun fell through the trees, dappling the leaves on the sidewalk under my feet. All that glorious light and color. We have plenty of time, I thought. In those days, I swaddled myself in denial; I rarely thought of Meredith as my dying friend; she was just sleepier than everyone else I knew.

“I want to write about you,” I blurted right before we hung up.

“Make me sound smart,” she said. “Use big words.”

“Of course. And footnotes.”

The jovial tone soothed me. We were simply two friends on the phone before the quotidian demands of our lives overtook the day. I walked north along the Metra tracks between 59th and 60th Streets. One hundred blocks away in Andersonville, she sat in her comfiest chair next to her cat and her husband’s dog.

“Oh, and do me a favor, will you?” she said brightly. I expected Can I pick my pseudonym? or Don’t mention my dentures.

“Sure. Anything.” Yes, I was still in denial about her illness, but lately, I couldn’t help but notice her whittled face and her jutting cheekbones, now sharp enough to slice an Easter ham. Somewhere inside me I knew she was slipping away. I would grant any goddamn wish she had.

“Please be sure it has a happy ending.”

I stood still on the sidewalk in a pile of yellow leaves, nodding and swallowing a cry. I didn’t like the word ending, and I didn’t understand the word happy in this context. How could I honor that promise if she ended up, you know, not making it? What kind of happy ending could I give her?

“Of course, a happy ending,” I chirped, and instantly hated the false, shrill tone of my voice—that wasn’t what we needed right now. We needed the firm, solid notes of honesty. “Mere, I’m not exactly sure how to do that.”

“Oh, honey. You do. Tell the truth. Tell how we helped each other let go of being so brittle and scared and unable to connect with so many women because of our own hang-ups. Tell them how we learned friendship. Together. Tell them how we changed by holding each other’s hand as we looked honestly at ourselves. Tell how one life can alter another.”

___________________________

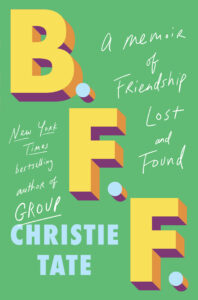

Excerpted from B.F.F.: A Memoir of Friendship Lost and Found by Christie Tate. Copyright © by Christie Tate. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Avid Reader Press.