Camonghne Felix on the Gentle Balance of Writing about Trauma

"I found ways to offer the reader reprieve and safe space."

The following first appeared in Lit Hub’s The Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Trauma is a sneaky beast. She shows up in our lives unexpectedly, and no one can evade her. Some of us spend most of our lives believing that we are safe, considered and valued—then trauma shows up (the death of a parent, an intense break up), and those things no longer seem true. It is disruptive, defining, and universal.

So it makes sense that so many writers and artists make art about trauma, personal and fictionalized — we write about universal themes because we want to be able to relate to our audiences. Few topics are as relatable as trauma.

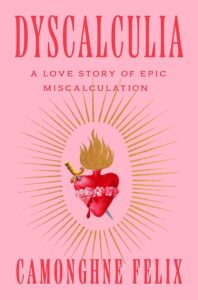

But encountering trauma in literature can be messy for the reader; to process it, they must give the text a significant amount of labor. They risk triggers and retraumatization and the author risks retraumatizing themselves too. It all seems inherent to the work, that trauma must be discussed and that it must be painful for everyone involved to be authentic. I have been guilty of this thinking myself, and I was in conflict with it as I wrote Dyscalculia, a book that is, at its simplest form, about trauma.

Many readers, to find value in the trauma narrative, need to know that there’s an end to trauma’s harm.

I knew it was important to include the authenticity, and important that I help inoculate my reader from the trauma, two goals that felt irreconcilable. Does it have to hurt the reader for them to get it? Must they really be in my shoes? I spent a lot of time considering this in my own work, and for a while came to no good answers, so for almost a decade I refused to write anything about trauma, unsure of whether or not I was doing more harm to my readers than not. And then, I began writing Dyscalculia, and I know I would need a working theory of how trauma would function in my book before I could put it out into the world. Through humor and by writing into a healing narrative instead of a trauma narrative, I found ways to offer the reader reprieve and safe space.

When we are in a traumatic moment, every single emotion plays out, including humor. But when we retell trauma, we almost never remember the humorous moments, or the moments in which one could do nothing else but laugh. Remembering those moments is what makes the retelling of trauma feel more real, because a reader understands that sometimes, the painful can be painfully funny. They want to read authenticity, and be able to see glimpses of their own painfully funny realities in yours. This is what makes it real, and what makes it bearable — that the reader is able to use laughter to help mitigate the trigger in their own bodies as they enter the work beside you.

In Dyscalculia, I talk a lot about what hurts. But I talk just as much about what it felt like to heal from that hurt. Many readers, to find value in the trauma narrative, need to know that there’s an end to trauma’s harm, and writing Dyscalculia offered me a profound opportunity to understand my healing as not just an event but a literary technique. Building the healing into the language helped me truly see which parts of the trauma were necessary to include, and where to pull back to offer my readers a way out of the book’s trauma.

As writers, we cannot avoid what draws us in. But we do have a responsibility to consider the concerns of our readers. We have a responsibility to take care of our readers, and ourselves, when writing about trauma. We can and should build techniques that allow us plenty of authenticity and plenty of restraint so that we aren’t exploiting our own stories and traumas for the sake of being read.

____________________________________

Dyscalculia by Camonghne Felix is available now via One World.

Camonghne Felix

Camonghne Felix, poet and essayist, is the author of Build Yourself a Boat, which was longlisted for the National Book Award in Poetry, shortlisted for the PEN/Open Book Award, and shortlisted for the Lambda Literary Awards. Her poetry has appeared in or is forthcoming from Academy of American Poets, Freeman’s, Harvard Review, Lit Hub, The New Yorker, PEN America, Poetry Magazine, and elsewhere. Her essays have been featured in Vanity Fair, New York, Teen Vogue, and other places. She is a contributing writer at The Cut.