At first I wondered why we needed to go to a gun show to buy a gun. After all, Charles lives about three miles from a store called Frank’s Gun & Repair. It’s at the corner of Highway 51 and 121st Street, just north of the Phillips 66 and across the street from the railroad tracks. Can’t miss it. Can’t mistake it, either, with its red-and-black-lettered sign spelling out 486-GUNS just below the word guns (again), in obstinate Republican red. Plus, Charles and the store owner, Frank, were downright social.

Indeed, Charles could buy, sell, or trade any one of the guns he owns there. I knew that Frank had recently serviced a handgun for Charles, after Charles had claimed that it wouldn’t fire and was probably a piece of shit. Frank took a look at it. Cleaned it. Lubed it. Rubbed it down and had the pistol firing like new.

So I thought Frank’s is where we’d go when I told Charles I had come around to the idea that I needed a Glock. But I soon came to learn I’d given Charles too good a reason to do what many gun owners do for fun: go see what somebody else has got. Guns are apparently a lot like baseball cards. Folks are in love with their own collection, envious of somebody else’s, and willing to shell out an obscene amount of money to get to brag about owning some rare specimen.

There’s not a whole lot Charles will travel for. Only recently has Nancy convinced him that staying a night in Branson, Missouri, or Memphis, Tennessee, ain’t gonna hurt him or the cattle. But if there’s a gun show in Tahlequah, about an hour east of Coweta? Or if the Oklahoma Rifle Association is having a meeting in Oklahoma City? He’ll set right out.

Finally, a couple years into my relationship with Lizzie, when we were engaged to be married, he’d begun to think of me as something like a son. That’s what this trip was—a father and a son going to buy the son’s first gun, at the world’s largest gun show. Truth is, without Charles, I had about as much chance of walking into a gun show all by my lonesome as a Carnival Cruise liner would have docking in Antlers, Oklahoma.

In Oklahoma, there’s a gun show almost every weekend of the year, which is right in line with the national trend. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives estimates there are more than 2,000 gun shows held in the United States annually. But the National Association of Arms Show puts that figure closer to 5,200, or 100 gun shows every weekend of the year.

Wanenmacher’s Tulsa Arms Show occurs twice a year; the show organizer claims it is “the World’s Largest Selection of antique, collector and modern firearms, knives, and accessories.” Usually lasting a weekend, the Wanenmacher’s show, located at the Tulsa Fairgrounds, covers 11 acres and boasts more than 4,200 tables and 7,000 vendors. Nearly 40,000 people visit the show on a given weekend. There’s parking for RVs and scooters for rent.

The first gun show put on by Wanenmacher’s was sponsored by the Indian Territory Gun Collectors Association in April 1955. A small group of avid enthusiasts met at a sportsman’s sporting-goods store called, I shit you not, Sportsman Sporting Goods. It was located in what has become midtown Tulsa.

The idea of holding a show came about as a means to compare notes on what other gun collectors across the state had in their gun safes. When Joe Wanenmacher became club treasurer in 1968, he also took on the responsibility of organizing the semiannual gun show. In 1968 Wanenmacher counted 117 tables at the show. Then, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Gun Control Act of 1968. This act was the federal government’s attempt to regulate the sale and transfer of firearms in the United States by requiring gun sellers to be licensed and by banning some small firearms. Attendance at the gun shows exploded the next year.

Two years in, Wanenmacher told the club he couldn’t run the show for little to no payment anymore. That’s when the club members asked him to take over the show permanently. The bargain was this: the show would retain the original club name, but all the profits would go into Wanenmacher’s pocket. Eventually, the club name—Indian Territory Gun Collectors Association—gave way to a new one: Wanenmacher’s. This was, perhaps, because the reference to the state’s theft of territory from whole nations of people—which happened twice—felt awkward, but most likely, Wanenmacher just liked his own name. A petroleum engineer by trade, the man sensed he was about to strike oil.

Over the past 48 years, the show has achieved international acclaim because Wanenmacher willed it so. He traveled widely, recruiting collectors and salesmen from three continents and every state in the Union. The NRA’s National Firearms Museum took a spot at a Wanenmacher’s show in November 2014, to display guns owned by President Theodore Roosevelt and Annie Oakley. The actors Dan “Grizzly Adams” Haggerty and Lash LaRue have signed autographs at the show, as have members of the crew of the Enola Gay. According to Wanenmacher, the actor Tom Selleck once dropped by the show, in secret, to make a purchase. Fewer than 20 percent of collectors and salesmen at the show are Tulsans.

Wanenmacher also changed the direction of the show.

The Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act went into effect in 1994. This law, supported by President Bill Clinton, banned semiautomatic weapons as well as high-capacity magazines. It also amended the Gun Control Act of 1968 to establish a five-day waiting period for unlicensed gun buyers. But, as with the passage of the Gun Control Act of 1968, the Brady Act of 1994 only brought more customers to Wanenmacher. Then the Federal Assault Weapons Ban expired in 2004. Four years later, a black man was elected president, and gun owners, mostly white ones, headed straight for the nearest gun show.

“A year after the founding of Black Lives Matter and two years after the killing of Trayvon Martin, it pained me and intrigued me to see the plethora of bumper stickers, T-shirts, and license plates with Confederate flags and dangerous rhetoric such as Heritage Not Hate.”“Our good president probably has been the best gun salesman we’ve ever had, even better than Bill Clinton,” Wanenmacher said in 2014. “I think . . . it’s the fear of what he could do and knowing that we have a president who is the most anti-gun president we’ve ever had that motivated people to hoard even though now it looks like those things won’t happen—at least not very soon.”

Charles and I visited Wanenmacher’s show in November 2014, the year before the show turned 60. Charles was dressed as he usually is. His polo shirt was tucked into his blue jeans, which he had pulled over the top of his cowboy boots. I was dressed as I usually am, in black hoodie, blue jumper jeans, and Jordan high-top sneakers. Charles took me around to the vendors, pointing out guns he thought were exciting or peculiar and stopping to chat with vendors whenever he felt gregarious. Whether my sense of vigilance was paranoia is debatable. I was painfully aware of how few black people I’d seen at the show. I didn’t need all my fingers to count them.

A year after the founding of Black Lives Matter and two years after the killing of Trayvon Martin, it pained me and intrigued me to see the plethora of bumper stickers, T-shirts, and license plates with Confederate flags and dangerous rhetoric such as Heritage Not Hate. One T-shirt I saw proclaimed this message: I just bought a new Glock, and I can’t wait to try it out on the next trespasser.

Here’s another: a gun in the hand is better than a cop on the phone.

And here’s one more: God made men, but Sam Colt made them equal.

The kind of people who buy those kinds of shirts made up the majority of people at the show, and I was decidedly not one of them.

We came to a vendor with a brand-new Glock 26 on display. “You want that one?” Charles asked. “I’ll buy it.” The Glock 26 is a subcompact, concealed-carry, nine-millimeter weapon affectionately known as the “Baby Glock.” It’s a pocket pistol specifically designed for self-defense. For that reason, the magazine holds just seven rounds, as opposed to the seventeen of other Glocks, and its grip is just long enough for an adult male to wrap three fingers around it.

The show features a list of 21 rules and guidelines. Among them is a warning to vendors: “You are urged, for your protection, to obtain and furnish identification for all sales.” The state of Oklahoma does not require that background checks be performed on gun buyers, and that’s as Wanenmacher wants it to be. Despite the fact that 92 percent of Americans favor background checks for all gun sales. Charles knows that anybody who wants a gun will get a gun. But he’s not afraid of a background check. He reached for his wallet to pay for the Glock. He was prepared to run this play the way the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives drew it up. He presented his I.D. and had a pen ready to fill out the Firearms Transaction Record for over-the-counter purchases. He was ready to allow the seller to give that information to the FBI, which would run it through the National Instant Criminal Background Check System, known as NICS.

The number of background checks performed by NICS has nearly doubled, from 11.2 million in 2007 to 21 million in 2015. Polls indicate that 14 million guns were sold from 2008 to 2011, while 20 million were sold from 2012 to 2013. Over 9 million guns were sold nationwide in 2015, according to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. But think of how many people don’t report gun sales because they don’t trust the government, journalists, or even nonpartisan polling and research institutions. And some states are slow to update even the data they do collect. But when Charles offered to show the seller his driver’s license, the seller waved away the gesture. “Obama ain’t gonna know,” he said. In fact, sellers have the right to waive this check, in accordance with the federal Firearm Owners’ Protection Act of 1986, as long as they do not derive most of their income from selling guns. A number of states have, however, established laws making background checks mandatory for the purchase of any firearm at a gun show. But many more, including Oklahoma, may never join those states requiring this sort of vetting. So it did not matter that Charles was more than willing to abide by societal precautions meant to keep guns out of the hands of people who might do harm. The sellers themselves weren’t.

Charles didn’t seem the least bit fazed by what had occurred. He and I continued to walk through the gun show, having a look around. But I was keenly aware that I was carrying a Glock in a box, among people who, I knew well, could be armed, card-carrying members of the Heritage Not Hate clique. Charles and I encountered a number of white men and women sporting shirts that read proud member of the basket of deplorables and hats saying make America great again. They puffed their chests like they’d just whipped a bull moose’s ass in a fair fight. What was more startling—the number of Iron Eagle, SS, and swastika trinkets being worn and offered for sale. I couldn’t move when my eyes fell on a full-on Nazi officer’s uniform on display and for sale. That was one thing. It was quite another to see how many white folks were clamoring to look at it up close.

I wondered, Has this been here all along? Is this the place where folks who hate me, and all other people who don’t look and believe as they do, feel no shame about showing it? I think I knew the answer before I consciously asked myself that question, but it scared the hell out of me all the same. It still does. I dwelled on that moment when, a week later, news surfaced about a flyer being circulated around the University of Oklahoma campus. It was titled “Why White Women Shouldn’t Date Black Men.” It alleged that biracial children “probably won’t be smart,” black men “are much more likely to have STDs,” and dating a black man “starts with rape and gets much worse.”

I wondered how many of the thousands of people who visited Wanenmacher’s that weekend believed those hateful things? How many of them might’ve tried to do harm to me or Lizzie, had they known we were engaged? This is terror.

Nearly all the people at the show seemed to be swapping, haggling, and hustling—all part and parcel of gun shows. Hell, when I was with Charles at another gun show, he saw a pink .22 rifle, the kind you might give to a Harley Quinn wannabe, and bought it because he just thought it was cute. He figured he might make it his truck rifle, the kind you keep on the gun rack in the back, just in case a doe crosses your path or you spot a coyote in the pasture. As Charles sauntered through the show, he had to fend off people asking You selling? How much? They just assumed he was selling because he was carrying the gun around with him. The scene reminded me of Jake and Elwood Blues, sitting in a posh restaurant and accosting a family at the table behind them: “Your women! I want to buy your women! The little girl, your daughters! Sell them to me! Sell me your children!”

At Wanenmacher’s, I was both amused and horrified to see two old white men in a thoroughfare, gesticulating and arguing over an impromptu sell that seemed to be going awry.

“Why’re you trying to Jew me down?” “Why don’t you just pay my asking price?” “You’re trying to give me a Mexican’s price.”

Every gun show enables haggling and hustling. You’ll see folks with signs mounted on backpacks, strollers, oxygen tanks, and even the shirts on their backs, advertising a gun for whatever the asking price is. In this instance, the haggling apparently created a safe space for yet another sport: throwing around racial slurs.

At the Wanenmacher’s gun show, folks ogled shotguns and rifles owned by dead presidents and generals. They haggled over the worth of various antique guns that no longer fired but held some value for someone who thought they were worth thousands. They bought their wives and girlfriends concealed-carry purses while purchasing for themselves calendars featuring half-naked (white) women holding exotic guns and one more banana clip for the assault rifle at home, because, well, you never know.

I began picking up gun magazines, to bring myself up to speed on gun culture, but mostly for the pictures: Guns & Ammo, Concealed Carry Handguns, RECOIL, Gun Fighter, and Black Guns. Was that Black Guns as opposed to White Guns? Rainbow Guns? Polka Dot Guns? On the cover it featured a tattooed white woman holding an EraThr3 Anorexia Rifle with Leupold LCD viewfinder. In the end I couldn’t make it through a single article that day—gun-magazine prose read like an echo chamber. Readers didn’t have to worry about reading anything “politically correct,” and gun manufacturers didn’t have to think for a minute that product placement wasn’t the whole point.

We left the gun show and got back into Charles’s truck. In the passenger’s side, I sat with the Glock, still in its box, laid in my lap.

“Would you teach me how to shoot this thing?”

This was the next step. I was ready to become a responsible, licensed gun owner. I needed to know what it meant to have a gun in my house and to have the audacity to carry it in public.

“Yeah,” Charles answered, with a jovial tone. “Sure. Teach you how next week.”

![]()

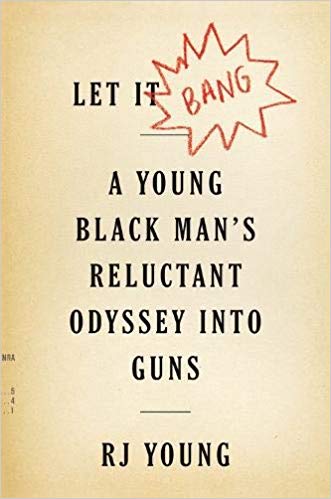

From Let It Bang, by RJ Young, courtesy Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Copyright 2018, RJ Young.