The case of Manako Kajii—or ‘Kajimana’ as she was known in the mass media—had intrigued Rika ever since her arrest. Rika had been part of a different news team at the time but the case had continued to niggle at her, and she was now approaching the age that Kajii had been at the time of her arrest. The election coverage she’d been involved with up until now was wrapping up, and it seemed that she would finally be able to start pursuing stories at her own discretion.

‘I bet Kajimana eats an absolute ton! That’s why she’s that huge. It’s a miracle that someone that fat could con so many people into wanting to marry her! Is her cooking that good, or what?’ Ryōsuke said.

A chill ran down Rika’s spine. She saw a frown flit across Reiko’s brow and then disappear. Reiko had always been even more sensitive to misogyny than Rika herself was. But it wasn’t that Ryōsuke was particularly insensitive. What he’d just given voice to was, Rika supposed, the standard response of the average man. The reason the case had garnered so much attention was that this woman, who had led several men around by the nose and maintained such a queenly presence in the courtroom, was neither young nor beautiful. From what Rika could see from the photographs, she weighed over 70 kilos.

‘Rather than trying to find a new lead in her case, what I’m interested in is the social background to it all. I feel that the whole case is steeped in intense misogyny. Everyone in it, from Kajimana herself to her victims and all the men involved, seems to have a deep-seated hatred of women. I don’t know whether I can really get that aspect across in a men’s weekly magazine like ours, but I want to try. I’ve written to her several times, though, and had no response. I’ve even been to Tokyo Detention House twice in person, but it seems she has no intention of meeting me.’

—I’ve been lonely so long that if I can find a woman to take care of me when I’m old, I don’t really care how ugly she is.

—I don’t care who she is, so long as she’s the domestic type who’ll make me dinner.

—She might be fat, but she’s a real cosseted princess-type. There’s something unworldly and untouched about her.

All three victims had come out with statements like these to the people close to them while they’d been still alive. They clearly had a powerful need for Kajii, and had presented her with significant sums of money, and yet in the presence of third parties, had repeatedly made disdainful statements about her. In court, the prosecution had thrown considerations such as alibis and solid evidence to the wind in order to launch attacks on Kajii’s concept of chastity, so their line of argument veered about wildly, and the trial had made slow, painstaking progress. One of the witnesses, a female care-worker for the elderly, was interrogated in a manner that many felt to be sexual harassment. The debate around the case was split down gender lines. Something that a prominent male critic had said on the topic had been deemed misogynist, and he had eventually been forced to apologise.

‘The last victim—what was his name again? You know, the guy who was kind of famous in online otaku circles? Just before he was run over by the train, he’d eaten beef stew that Manako Kajii had cooked for him. I wonder if that was something she learned to make at that French cooking school—what’s it called again? Oh yes, Le Salon de Miyuko!’

It seemed from the information she had at her disposal as though Reiko had been avidly reading up on the case, both in the weekly magazines and online. She liked to have her finger on the pulse, keeping up to date with the latest news and trends, and she was also the industrious, diligent type, with a passion for research. At university she had consistently been top of her class.

Le Salon de Miyuko was a women-only cooking school that was well known among a certain social elite. It had been set up by Miyuko Sasazuka, wife of Mr Sasazuka, the owner-chef of the famous French Restaurant Balzac in the affluent Nishi-Azabu district of Tokyo. On Balzac’s day off, Miyuko Sasazuka, who herself worked in the restaurant with her husband, took over the premises to run the cooking school, whose selling point was that its students not only had full run of the Balzac kitchen, including the professional ovens and cooking equipment used by its chefs, but would cook with the restaurant’s finest-quality ingredients. At 15,000 yen a lesson, the fees for the thrice-monthly classes were far from cheap, and a year’s attendance would set you back over 500,000 yen. Nor did graduating from the course give students any kind of certification, or ability to turn professional. The classes were rather like an extremely opulent pastime, permitted only to wealthy housewives and women with high salaries. Up until two months before her arrest, Manako Kajii had been avidly attending the school, with her fees paid for by one of her victims. A quick search on the internet soon yielded a group photograph from the Salon, showing Kajii standing with the other students. Among that group of stylish women attired with impeccable taste, Kajii, in a tight-fitting dress that accentuated her voluptuous figure and would have been more suitable for a ritzy date than a cooking school, stood out like a sore thumb. Now, after being hounded by the press, the cooking school was on a break.

‘Yes, apparently right before the victim died he sent a text to his mother: My girlfriend made me beef stew! It was delicious. Remember the argument of Kajii’s lawyer in court: would a woman who’d spend all that time cooking up a delicious beef stew for her lover really push that same man in front of a train? Listen, Rika, next time you write to her, why don’t you try asking her if she’ll share the recipe with you? I bet she’ll agree to meet you after that.’

Rika blinked. The idea had never even occurred to her. Back in her time working in PR, Reiko had often used her thoughtfulness, humour and talent for conceiving of unexpected gifts to win over difficult film directors, talent agency presidents and sponsors, and bring them round to her way of seeing things.

‘Women who love to cook are so delighted when someone asks them for a recipe that they’ll tell you all kinds of things you haven’t asked for along with it. It’s a law of nature. I’m exactly the same.’

‘It’s true, you know,’ Ryōsuke piped up. ‘A little while ago one of my colleagues came round with his wife and kids, and was really impressed by the shūmai that Reiko made. So Reiko started telling him in detail how to make them, the kinds of steamer you need and all this. She got so carried away that he was quite taken aback,’ he said, laughing.

‘Hey, Ryō, I wouldn’t mind going to Le Salon de Miyuko one day…’

‘Not on my kind of salary, I’m afraid!’

Dessert was home-made candied chestnuts, chiffon cake baked with amazake and rice flour, and cups of gingery chai. Biting into the cake, Rika discovered that it was perfectly fluffy, with a pleasing springiness and bite to it. Yet when she widened her eyes and sang its praises, Reiko frowned remorsefully.

‘What with Christmas coming up, I wanted to make a thick buttercream buche de Noel, but of course without any butter that’s off the table. Rika had a look as well, Ryō, but it seems like there really isn’t any to be found around here. At this rate, pound cakes and sponges won’t be on the menu for a while. We’re left with chiffon cake, I guess: it’s about the only thing you can make with rapeseed oil.’

‘But this is so dense and squidgy, even without it! It’s great. It looks like the butter shortage is going to drag on, anyway. They’re saying that with the heat last summer, lots of dairy cows got mastitis, and that’s what’s causing it. But this is after they forecast a supply shortage, and imported a load at the last minute as an emergency measure. So where’s it all got to? I wonder. Saying that, though, there are fewer and fewer dairy farmers in Japan these days. I’m guessing that there’ll come a time in the future when we’ll just import all our dairy products from overseas. In any case, it’s a real blow for a small company like ours.’

As she listened to Ryōsuke and made the appropriate responses, Rika recalled that Manako Kajii had a soft spot for butter. Rika’s interest in food was so limited that she’d only skimmed Kajii’s blog, but she did remember that Kajii had gone on and on about expensive brands of butter. Come to think of it, there’d been a discussion in court about how Kajii had taken one of her victim’s credit cards and used it to buy numerous packets of butter costing nearly 2,000 yen a pop. Kajii had grown up in Niigata, surrounded by dairy farms, so maybe that explained her pickiness. Her fixation had been thoroughly mocked online, with people making comments like, ‘No wonder she’s that big if she eats so much butter’, and, ‘It wouldn’t surprise me if she used her sticks of butter for you know what…’

Just past nine, Rika said her goodbyes, politely rebuffing the pair’s entreaties for her to stay longer, to sleep over and leave in the morning. With the onigiri made of the oyster-and-vegetable rice and the piece of chiffon cake wrapped in clingfilm that Reiko had handed her tucked inside her bag, Rika headed for the office.

I only want to spend my time with people who know the real thing when they see it. People who truly understand the value of the real thing are few and far between. These kinds of lines appeared frequently in Manako Kajii’s blog. Someone who knew the real thing when they saw it—surely it was hard to find anyone that applied to better than Reiko, thought Rika. In front of the ticket gates, Rika turned around and looked back once more at the neighbourhood. The cluster of lights from the new houses leading up the hill now seemed to her warm and inviting. When she reached for her train pass, she noticed that her fingertips looked less dry than earlier, and her hangnail less severe.

__________________________________

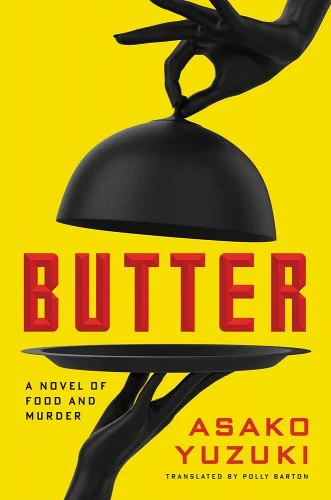

From Butter: A Novel of Food and Murder by Asako Yuzuki, translation by Polly Barton. Copyright © 2017 by Asako Yuzuki. English translation copyright © 2024 by Polly Barton. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.