He let the fire burn down to embers, let the dark envelop him, and stood.

Jess stepped to the edge of the trees and looked down to the water. It was a big lake and he could see only the bay and the curve of the wooded shore and he could see that the water held there was nearly glass. The black mirror floated countless stars, and the stars barely rocked. He lifted his eyes to where they held fast in the depthless sky and he saw among them a satellite sailing swiftly east to west, and he wondered what it might be witnessing in its silent transit.

If he himself could be a night bird, like some great horned owl on soundless wings, would he fly north over the next town, over the road beyond it? Randall, that was the name on the map, wasn’t it? Would he want to see? Probably not.

In the days since they had found the bridge over the river blown and no way south he had dreamed hard every night. Dreams on dreams, with segues like swinging bridges. He had dreamed of their house, his house now, but it stood in the sage of some high western desert unprotected by a single tree, and the rail fences were broken, the horses vanished. In the dream they had more than one horse, but he couldn’t remember how many or if he had asked a neighbor to care for them while he was gone. Because he was gone. That was the gut weight of the dream, his own absence from anything like home. He dreamed the return again and again, a homecoming only as much as an old negative represented the photographed image, a homecoming that was as much a leaving, and she was never in it. He called for her inside a house he no longer recognized, and again and again in successive nights he walked around the house to the back, to the clothesline stanchions that gestured like empty crosses, and he found a well and he called for her there and dared to look down it and received only cold echo. He woke from that dream with the pillow of his rolled jacket wet. He lay in the wash of his own story and let the sound of a faint broken music trail off, and he let himself cry, and almost as soon as he gave himself permission to sleep he was pulled back into the dark. There was no swimming above it.

He dreamed then that he was in a pasture digging, first with a spade, which he laid down so he could scoop back the finely graveled mud with bare hands, the ditch some kind of drain, and when he stood he saw a former lover walking past the white clapboard house, her glance back seductive the way any vista is seductive just passing out of view. But he didn’t know her. He should but he didn’t. She had large dark eyes, as Jan had, and his longing was for something familiar, some beauty that rolled in his raw fingers as the prayer stone she had given him rolled now, while he stood with the trees at his back.

She called it a prayer stone. It was the size of a radish and taken from their favorite creek and given to him as a reminder to pay attention: Love is attention, she’d said. That is all you know on earth.

He had it in his pocket now, and as he stood at the edge of the woods and watched the drifting stars jostle barely on the water like faint semaphores, and smelled the cold sediment of the lake and the cold char of the town, he squeezed the stone in his right palm and wished he could signal her as the sparked reflections on the water seemed to blink to the thrown galaxies arching above: I am here. Forever rhyming, forever loyal.

Or maybe it was just an unheard music that time and space could never quiet. A music that turned and turned like a horse in the wheeling dark. And with that thought, and the warming stone chafing his palm, he thrummed with a grief and love so immense he could not contain it. To stand here. To breathe. To witness. He thought wildly in that moment, They better be enough.

__________________________________

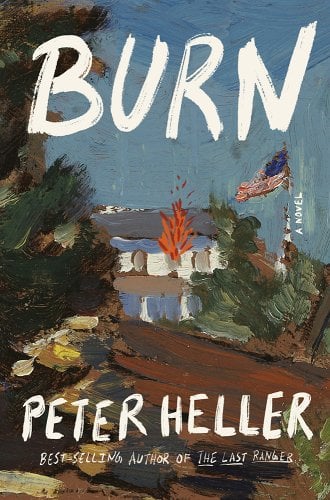

Excerpted from Burn by Peter Heller, published by Knopf, an imprint of the Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Bear One Holdings, LLC.