You don’t need to know the physical geography of Dublin, Ireland’s capital city, to read this essay. Indeed, even if you were a regular visitor there or an inhabitant of one of Dublin’s more affluent suburbs, it is still unlikely that you would be able to frame a mental picture of the specific location I have in mind: an isolated river road that I never traverse without thinking of one particular Bruce Springsteen song.

When I call this road isolated, I don’t mean in the sense of it being a remote, picturesque byway. Certainly there was a period in my 1960s childhood when it retained a rustic visage and local families from the vast working-class neighborhoods of Cabra and Finglas—the two Northside suburbs separated by this river valley—would picnic here on summer evenings at a bathing spot called the Silver Spoon. Older boys stripped to the waist would jostle about, anxious to impress teenage girls while younger children waded in the water with cheap, tiny nets to catch pinkeen fish.

Today one side of the road is lined by the railings of a nondescript park that falls down to the river, on an incline too steep to build on. The other side is lined by small industrial units—timber and building merchants’ providers, car parts suppliers, tire companies, electrical wholesaler trade providers, and a car wash for taxis. There are other anonymous small warehouses with poor signage that obscures their exact purpose from the casual passerby.

Not that you find too many casual passersby on that river road after six o’clock when the steel shutters are pulled down. After dark it possesses such a desolate sense of being on the edge of town that few pedestrians venture along it and motorists never stop because they are simply passing by, speeding along this stretch of limbo on journeys invariably destined to end elsewhere.

It is a stretch of road where a young couple, with nowhere else to go, might sit undisturbed in a car to express their love and confide their dreams or perhaps, after dusk comes, slip through the drab railings into the steep unlit parkland where the River Tolka flows. I have no rational explanation for making this connection, but in my mind this roadway will always be the landscape of Bruce Springsteen’s classic song “The River.” On a geographical level this is nonsense. The Tolka is so insignificant a river that it would barely be noticed as a tributary to the actual river Springsteen had in mind when he wrote the lyrics of “The River”: lyrics resolutely American in their setting.

But those same lyrics remain resolutely universal in how they conjure up the fragile scenario in which young people’s hopes are crushed by economic circumstances. The life story of his hurt and hurting protagonists seems, at a first listen, to be encapsulated in the two titles employed by Nadezhda Mandelstam when she chronicled the life of her husband, a Russian poet of genius purged by Stalin. Her book titles were Hope against Hope and Hope Abandoned.

However, the more you live with Springsteen’s lyrics the more you realize how—even amid the seeming economic and emotional implosion of their dreams—Springsteen’s narrator still clings to what another poet, Leonard Cohen, called a “little wild bouquet” in refusing to allow his spirit to succumb to utter despondency. Even if all that buoys him up—on nights when home feels too lonely a place to return to—are his memories of first love once found by that river, the small flame of those memories remains a benediction that refuses to be quenched.

Therefore, despite the vast dissimilarity between the river that Springsteen had in mind and the Dublin backwater that his lyrics conjure up for me, I cling to the notion that my unexceptional river road of drab industrial units bordered by an unlovely park still retains the right to be counted as part of the true—if not literal—emotional landscape of his song. This is to say that it is as true an emotional landscape for “The River” as are hundreds and probably thousands of other stretches of water across the globe that other listeners to that song immediately summoned up in their minds when they first heard its opening lyrics.

Listeners of “The River” are transported from the particularity of one New Jersey couple into the universality of millions of couples, past and present.It is no small feat to write a good song about one particular place, but it is a far greater feat to write a superb song that, at its heart, could actually be about any place. A Dublin writer, Samuel Beckett, pulls off this same feat in creating a relatively anonymous location, or almost a dislocation, for his 1953 play Waiting for Godot. I have never seen any performance of that play without transporting it in my head to the Dublin Mountains where Beckett so often walked as a young boy. But, although a Dubliner, Beckett chose to write this play in French and then translate it back into English, adding to its oddness by initially forsaking his native tongue.

Therefore, I know that a French audience will feel an equal emotionally territorial possessiveness in locating the setting of the play as being some remote crossroads in France. Indeed I have no doubt that Sri Lankan or Somali audiences make similar mental readjustments in an effort to try to imaginatively enter Beckett’s mindscape.

Of course “The River” is utterly different to Beckett’s play in that while Beckett deliberately sets Waiting for Godot in a disconcerting landscape on the edge of nowhere (and therefore the edge of everywhere), Springsteen does not try in any way to clock the real physical setting of “The River.” He has been upfront in stating how the song was inspired by early difficulties encountered by his sister and brother-in-law in starting out on their life together. It becomes a homage to their resilience and love while also offering a social critique of the human collateral damage of economic collapse and social inequity brought on by factors beyond the control of ordinary workers with no job security.

Therefore, the song is rooted firmly in the particulars of New Jersey life. Yet because it hones in so closely on the human tragedy at its heart, our emotional viewpoint focuses so tightly on the tense silence within the rooms where the protagonists try to cling to the last visage of fractured dreams that we find ourselves almost passing through that silence and reemerging out the other side. Listeners are transported from the particularity of one New Jersey couple into the universality of the millions of couples, past and present, whose lives and dreams have, at some time or other, been ensnared within the same familiar scenario.

Not just “The River” but so many of Springsteen’s other songs spill out from their origins to become infused with other lives and other places. They create an imaginative landscape where radically different people in radically different circumstances and, indeed, on different continents, can all simultaneously feel that he is somehow addressing them; that he is articulating the hopes, dilemmas, and realties of their lives; that somehow Springsteen has stood by the diverse rivers which his song conjures up and that he has captured the essence of emotions that his audience has felt in their lives.

This emotional response to his songs is different from imagining that we somehow have a nonreciprocal, parasocial relationship with their author. It simply means that something in their very essence rings true in our core and that, most especially when we are young, they become touchstones for articulating emotions that we may not as yet possess the vocabulary or emotional maturity to fully express ourselves.

*

I am a Dublin-born poet, novelist, and playwright from a city awash with a rich literary heritage: the city whose population has grown to over a million and a quarter in recent decades, but which was far smaller when it was the home of future Nobel Prize for Literature winners like Beckett, George Bernard Shaw, and William Butler Yeats (and more recently the adopted home of Seamus Heaney) and of world-famous writers who equally deserved this accolade like James Joyce, Oscar Wilde, and Seán O’Casey.

Literature was always hugely important in the Irish national consciousness, not least because we endured a foreign occupation and gained our independence only following a series of armed upheavals during and after the First World War. When any small nation is forcibly ruled by a militarily stronger power, the center of political influence (and therefore the moneyed classes who become patrons of high art like opera, classical music, and portraiture) shifts to that foreign center of power—which, in Ireland’s case until 1922—was the British Parliament at Westminster in London.

There was a sense that the song was simultaneously addressing all of our lives or the lives of people whom we knew closely; that we were all visualizing different stretches of rivers.However the two art forms that can thrive without such rich patronage are literature and popular music. This has made the articulation of the Irish experience by Irish authors and songwriters central to Irish people’s awareness of their shifting identity.

All of this is to say that, when I was a young factory worker, making welding rods in the working-class Dublin suburb where I was born, Dublin’s existing literary heritage was so vast that it might seem odd that I would need to look elsewhere for words to resonate with and echo the experience of life around me. Whenever I walked through the center of Dublin, I was always acutely aware of traversing the same streets through which James Joyce’s all-too-human fictional creation, Leopold Bloom, walked during the tumultuous day minutely described in Ulysses. However the Dublin that I truly inhabited as a young man was not the Dublin of Joyce in 1904 or of O’Casey, whose plays brilliantly explore tenement life in the early decades of the 20th century.

Those great Dublin writers might have felt like ghostly forefathers on the shoulders of every young Dublin writer of my generation, but they could not describe our new world of factories and dual carriages and the sprawling new working-class estates in which some of us lived, simply because Joyce and O’Casey had not lived in this new environment that we were living through and in which we were all, in different ways, starting to find new ways to express our experiences.

The fact that a songwriter with the power of U2’s Bono and a novelist with the power of Roddy Doyle both lived only a mile or two away from me and were both among a whole generation starting to explore the imaginative boundaries of our shared world means that it would be a matter of a few years before the Dublin of my generation did indeed find its fresh and original voices to articulate its experiences.

But such local voices were still only starting to develop when, aged 19 in 1978, I commenced my first job doing shift work in a welding rod factory and celebrated getting my first small brown wage envelope—it was cash in those days as not everyone had bank accounts—by purchasing Bruce Springsteen’s recently released Darkness on the Edge of Town. Some musical moments on that album felt a tad bombastic and overblown, as if their emotion was unearned. But other, more stripped down moments seemed to speak directly to me and my experiences in a way that, as yet, the words of Joyce and O’Casey did not.

Even today I still rarely hear one track from that album, “Factory,” without remembering how I would often play it in the early morning when I returned home at 7:30 from a night shift. Looking back now, I can even see how its imagery influenced one passage in my long-out-of-print debut semiautobiographical 1985 novel Night Shift, which was based on my time working in that welding rod factory.

I call the novel semiautobiographical because it describes many of my own experiences as someone in their late teens who was suddenly thrust into the very adult world of factory life, where a shop steward was organizing a very bitter protest action about working conditions and I found myself laboring alongside grown men who were twice or three times my age. However some of the experiences that happen to the novel’s central character were most definitely not my own. This is because they borrowed from the real-life experiences of one of the few other young workers in that factory.

Although only a year older than me, this young man found himself already married after his girlfriend became pregnant and he did what was perceived to be the decent and expected thing in those days, which was to get married before the bump of his bride-to-be grew too pronounced. I didn’t know him well, but some other young workers in that factory often talked about how, when they went courting with their girlfriends, they occasionally sought out isolated stretches of the River Tolka that afforded some privacy for youngsters with nowhere else to go.

Two years later, in early December 1980, I had left that factory and was working in a different job when one night I found myself with some of my fellow workers invited back, after a night in the pub, to a house in another working-class Dublin suburb. Our host was a young van driver whose wife was in bed, their child asleep. But his young wife woke up and came downstairs to sit and drink and chat with us as he took out a new double album that he had just purchased and wanted to play for us.

It was, of course, Springsteen’s The River and, as the title track of the album started, he said quietly, “This song is my life: this song is about me.” He wasn’t long in this new job, and, as that night was the only occasion when I ever visited his house, I do not even recall his name now. Therefore I have no knowledge of which circumstances within the song he most identified with.

Springsteen’s songs helped me to an understanding that my world of Dublin factories and working-class estates was as much the source of literature as Greek mythology.I just remember all the chatter in the room dying down, so that the ten people there were suddenly all intently listening to Springsteen’s lyrics. In that moment there was a sense that the song was simultaneously addressing all of our lives or the lives of people whom we knew closely; that we were all visualizing different stretches of rivers in different locations in our mind, none of which Springsteen had never set foot in, but all of which had suddenly been brought to life by his lyrics.

For me, the location of that song instantly became the Tolka and its protagonists became that welding rod factory worker who was barely older than me whom I had worked with two years previously: a young man who had married his childhood sweetheart with love but also with haste. I have no idea how their lives panned out, no more than I have any notion of what happened to the van driver who first played me the song—on the very night, by sheer coincidence, when John Lennon was shot and we all woke on a living room floor to hear “Imagine” being played constantly on every radio station.

Looking back across the years, I wish those people nothing but happiness, but all I know about them for sure is that they—like thousands of others in thousands of other places—probably still pause for a moment and reflect whenever the opening chords of “The River” get played on the radio.

Needless to say, Bruce Springsteen did not make me a writer, although his lyrics opened up ways in which I could imaginatively address my own experiences. From the age of 14, writing was all that I ever did and even if I had not published 14 novels since then and seen over a dozen of my plays performed, it is something that I would still be doing every day after coming home from whatever job I worked. This is because writing is my way of making sense of my world, my way of creating my own space where I am not a consumer but an individual. It is the most intimate sphere where, whether alone with a pen and paper or the blank screen of a laptop, I know there is nowhere for me to hide from what I really feel inside.

But what Springsteen did in those hugely influential early albums was write songs that seemed to speak directly to me; songs in which he seemed to validate my life experiences and the life experiences of people I worked with. His songs helped me to an understanding that my world of Dublin factories and working-class estates was as much the source of literature as Greek mythology or the dreary snobbish Bloomsbury set.

Springsteen was by no means the sole influence in helping my teenage self find the confidence to write about my own life. I drew similar inspiration from someone like Phil Lynott of Thin Lizzy, in whose lyrics I heard my hometown mentioned for the first time in rock music. Today, young Dubliners grow up with a whole different musical legacy to draw inspiration from, starting with the vast oeuvre of U2. Today, I also understand enough about life to have assimilated my own literary heritage of Joyce and Beckett whose words have turned my native city into a universal landscape of the imagination.

But I have never forgotten how those Springsteen albums were such important stepping stones. I have never met Springsteen and never expect to do so. But I know the two words that I would say to him if I did, because I have witnessed the depth of experience and emotion that these two simple words can convey. Irish music was revolutionized in the 1960s by a group of bearded Dublin men who took the ballads of their people and injected new life in them, in the process becoming almost the Irish punks of their time. This group, who for decades became internationally famous, were called the Dubliners.

I count myself extremely fortunate to be a friend of their last surviving member: the great fiddle player and composer John Sheahan. I was walking with John late one night when we passed a rather rough bar where a number of smokers were clustered on the steps. I heard one man shout loudly and begin to walk after us. I felt that I was in one of those knife-edge situations in any city where you do not know whether to stop and confront your pursuer or walk quickly on.

But John knew what to do. John quietly stopped and turned to face the man who, although down-at-heel in appearance and the worse for wear from drink, drew himself up to his full height and held out his hand to shake John’s hand. Speaking with dignity and obviously summoning what the decades of listening to John’s music had meant to him, this man said the two words that summed up all that needed to be said before he turned and walked away. The two words I’d say to Bruce Springsteen: “Thank you.”

__________________________________

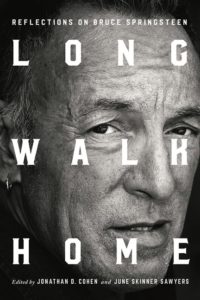

Excerpted from Long Walk Home: Reflections on Bruce Springsteen edited by Jonathan D. Cohen and June Skinner Sawyers. For more information about the author see www.dermotbolger.com.

Previous Article

Since When Did Animals Become Synonymous WithOur Grief?