Brooklyn Is Where the Heart Is: On Leaving Home to Write About It

Xochitl Gonzalez Considers the Power of Memory in Creating Literary Detail

The New York City of my youth was a cesspool. The trains were still covered in graffiti, you definitely worried—actively—about getting “jumped” or mugged pretty much anywhere that you went, and Brooklyn was a conjoined string of territories ruled over by “posses” or corner boys. As a kid, I felt myself as hampered, not defined, by this chaotic city. Like Esperanza from The House on Mango Street, I was desperate to get out of my weird little house with its railroad rooms; yearned to run away from my desolate block at the edge of an industrial park. Like young Dylan Ebdus in The Fortress of Solitude—a character I would only meet in adulthood—I believed that Brooklyn was not only a place not for me, it was not of me.

One semester into my four-year stint on a sprawling, manicured New England campus and I realized I had been fundamentally wrong about all of it. The grime was a sign of authenticity, the violence the stuff that toughens one up, and the street politics, I realized, had quite literally been ingrained into my worldview. I would put my headphones on and blast the newest New York rap mixtapes that I’d have picked up on Canal Street during my last trip home and walk the streets of Providence desperately seeking approximations for home—a record store here, a nail salon there, a Dominican joint on Broad Street. The substitutions were poor. I would wake up craving the taste of coffee cart coffee and stale buttered rolls, the smell of roast nuts that they sold on the streets, the crush of bodies during a Saturday stroll through SoHo.

And then I came home again. Delighted in my new appreciation for home, yes, but eventually, re-acclimated. And quickly my senses became dulled to all that messy life that surrounded me as I began to take it all for granted.

Until 20 years later when, for only the second time in my life, I found myself living outside New York. At the age of 42 I was admitted to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and, well, when Iowa calls, you answer. (Also, apparently, the only way to lure me out of New York City is the prospect of a degree. I will take that note up with my therapist.) So, I packed up my rent-stabilized apartment and the first 200 pages of my novel about native Brooklynites grappling with family trauma and gentrification and moved to Iowa City, Iowa.

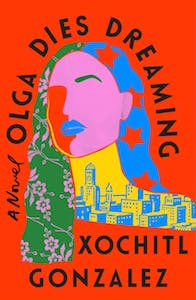

Prior to leaving home, I had been writing rather furiously—as much as my day job would allow. The sense of place was such a critical ingredient of the novel—which is now Olga Dies Dreaming—and I was concerned that once I was gone from the place itself I wouldn’t be able to recall for the page the details that, for me, bring Brooklyn the place to life. I was certain that if I didn’t vomit each sight or sound or smell down before I put my last box on the moving truck, that detail would be lost forever.

Instead, I found the opposite to be true.

The differences between Iowa City—which certainly has its own charms—and Brooklyn are too vast to mention, but my main, initial takeaway was shock at the sparsity of it. How many blocks I could walk without ever encountering another human being. I had never experienced the sprawl of the Midwest. I found myself walking the streets of Iowa City, filling them in with the crowded recollections of home: the delightful teen chaos of the Fulton Mall once schools let out; the domestic flurry of Fifth Avenue in South Brooklyn on a Saturday afternoon; Canal Street littered with bootleg “luxury” fashions.

I found myself walking the streets of Iowa City, filling them in with the crowded recollections of home.

The second surprise for me was the shock of quiet. I had opted to move to a part of Iowa City known as “downtown,” which I quickly realized was a mild misnomer because the name implied that there was an uptown or a midtown. In reality, there was this five-square block area with shops and some bars, and then there were all the other parts of town where everybody lived. Minus the raucous sounds of drunken undergraduates going to and fro on weekends, the sound of Iowa City, as far as I could tell, was silence.

I would lie in bed at night and imagine all the noises that I wasn’t hearing. No cars passing by blasting the latest banger from Drake, no kids wearing portable speakers whizzing by on bikes, nobody calling from across a street to their kid or their friend or their lover, no sirens, no jackhammers, no Salsa, no Reggae, no Shabbat sirens, no call to prayer from the Mosque on Atlantic Avenue filling the air.

The water in Iowa City was different, which resulted in the food all tasting different, too. The burgers from George’s and John’s fried chicken were delightful, of course. And Iowa City might have some of the best authentic Chinese food I’ve encountered. But, I found myself longing for tastes I had not realized were so specific to home: the tang of picadillo in a perfectly fried empanadilla! The heat of great jerk chicken from a barrel grill bought off a corner on Nostrand! Latkes! A million times, latkes!

And I was, admittedly, that first semester, quite lonely. I had returned to school after a significant absence, a middle-aged student surrounded by 20-something peers. My friends at home would call me early in the morning before they left to tend to their careers and kids and household responsibilities, and I was left with the day before me. And all of this longing. All of this flat space of Iowa City that made me anxious with how… uncrowded it all was. So much sensory space for a girl used to sensory overload.

And so to calm myself, to fill in the blank spaces, I wrote my world as best as I could from far away. I wrote the subway ride to home, I wrote the parking lot of a catering hall looking out onto Sheepshead Bay, I wrote bagel stores and 40-ounce bottles of malt liquor and bodega coffees and buttered rolls and music. So much music. All of it was probably more heightened on the page than it even exists in reality, but each detail felt so vivid in my mind because I craved to reach out and hold it, hear it, bite it, smell it, taste it.

As I found during my time in Providence, as soon as I got away from home what I found was not only a new appreciation for it but a longing. A pain, almost. And also a deep, deep fear. Brooklyn, like many cities, is in the crosshairs of rapid change. I never knew if the version I left to go to Iowa City would still be standing when I got back. So I poured out each memory onto the page. To fill in all the vastness that I found in Iowa City.

I consider this novel, my first, a love letter to Brooklyn, but I realize now that I could never have written this book, in this iteration, without my time in Iowa. Because to love something is to long for it. And you simply cannot long for something without knowing what it is to be apart from it.

__________________________________

Olga Dies Dreaming is available from Flatiron Books. Copyright © 2022 by Xochitl Gonzalez.

Xochitl Gonzalez

Xochitl Gonzalez received her M.F.A. from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where she was an Iowa Arts Fellow and the recipient of the Michener-Copernicus Fellowship for Fiction. Olga Dies Dreaming is her debut novel. Prior to writing, Xochitl wore many hats, including entrepreneur, wedding planner, fundraiser and tarot card reader. She is a proud alumna of the New York City Public School system and holds a B.A. in Art History and Visual Art from Brown University. She lives in her hometown of Brooklyn with her dog, Hectah Lavoe.