Brendan Shay Basham on the Similarities Between the Chef Life and the Writing Life

"Processes are a series of moments in passing."

I used to be a chef. Some might say “once a chef, always a chef—.” I don’t. I cooked through college to pay the rent, and some of my bosses were cool enough to let me experiment because I was curious, wanted to learn more about how things are the way they are. I came to understand this as art-energy. It was raw tongue and fire-proof hands and swollen feet in 120-degree heat.

Food haunts me like music does. Sometimes a flavor reveals itself in color, other times the sound of butter crackling in a hot pan is a sign from the universe—I must walk off the line to play drums or jump into the ocean, exchange sweat-salt for sea salt. There is magic in food. Yet I dreamed of wriggling my way out to become a writer, which my body understood but my brain had been convinced was an unattainable dream.

I co-owned a restaurant in Puerto Rico for nearly ten years. I was born with salmon on my tongue, but my family comes from the tops of extinct volcanoes rising from the desert in Dinétah in Arizona and New Mexico. When I missed home I ordered fresh Anaheim chiles to roast, skin, and freeze, and I had beans and hominy shipped in for brunch, that most-hated shift of our brood. We made our own bacon with heritage pork bellies, baked biscuits, made our own sausage. Everyone raved about the duck confit hash, crisped in smoking duck fat, topped with a poached egg and hollandaise.

I ate a lot of fish down there: blackfin, skipjack, yellowfin. I cut dorado so fresh, their muscles twitched as if tickled by my fingers in their open bellies. Braised lamb shank was another favorite—braised anything, really, because it’s the process that matters most, the slow build, the long simmer in a low-temp bath. One of my favorite things to prepare was duck. The ones we got slid out of a waxy cardboard box naked and headless. The breasts I cured and smoked. I would confit the legs in their own juicy juices, and roast the rest of the carcass for stock.

Processes are a series of moments in passing. We get better, more efficient, at the peel, fry and smash of tostones from a branch of platanos a farmer drops off ten minutes before service. I was determined to be defined not by my final product, but how I drove up the hills in Rincón in search of green papayas to yank from their milky stems in order to make that famous salad. More than the customers’ preferences, I was interested in the communities we built, in part by sourcing locally: we had potion-makers, brewers, distillers; I chose fishermen based on how burnt beyond red they were—crisp—and because their rates were fair, and they bled the tuna well.

What I didn’t realize until later was that chef-life was part of my training as a writer.

I wouldn’t let my cooks call me ‘chef,’ kind of like how later I only half-believed myself if I introduced myself as a poet or writer. For a second there I thought I may have been one of the nicest chefs I’d ever worked for, but it didn’t take too long for me to resemble the kind I hated, the red-nosed and puffy-eyed cynic, mean and conceded, the pride of a tidbitting cock a shining display of red waddles, combs, and giblets. Maybe I wasn’t cocky, though I did start to feel rage, and frequent panic attacks. Chefs rarely mean anything personal when they scream at you through the server window; we’ll always drink Medalla and whiskey after the shift, blasting Motörhead or Madonna if that last table ever gets up.

Kitchen work gets you down, burns you out. Maybe you’ve heard it’s tribal, too. My first kitchen job, I recognized kin in those clowns preparing delicious, precise, and consistent food at a frantic pace, and I admired them. Between the age of 18 and 34, I worked in restaurants in Flagstaff, Santa Cruz, Portland, Olympia, Fairbanks, New York, Chicago, Rincón. No matter where I went, there they were: fellow misfits and migrants and mentally ill, vagabonds and artists, a wild tribe where I felt comfortable, but didn’t belong, necessarily. I was smart (i.e., anxious) and ambitious and ever-expanding. I out-grew it long before I had a chance to call myself a proper chef. I was, after all, still just a sensitive poet-fish out of water.

What I didn’t realize until later was that chef-life was part of my training as a writer: I was absorbing a sensory vocabulary, inventing new language. I saw flavors before I tasted them. I could smell how three items on a plate bloomed in front of a customer before I even poached the pears or braised the pork belly or reduced the balsamic. The texture of crispy duck begged for the dark red sweet of roasted cherry tomato. I don’t recall if I was synesthetic before, or if it’s something one can cultivate, but it effects our very nature of perception, which became a source of power for my novel.

I made a living as my own boss at a popular fancy restaurant on the beach in Puerto Rico, which sounds like a dream, but I became someone I didn’t recognize anymore. Eventually, as I felt myself fade away from cooking and the industry altogether, I made an active decision to leave in order to change, transmute. It’s a life I could have made work, but at great sacrifice. I wasn’t bored so much as exhausted. If I didn’t write my way out, chances are I would have died under a palm tree with a swollen belly and leathery neck.

What is this about—that longing? It feels like a quest for transmutation, acceptance of constant growth and change. Less about the search for compatibility than it is about recognition: to be seen versus to be on the margins. Will I forever feel like the outsider, the duality of Navajo woman and white man, the bi-polar, simultaneously creative and logical crazybrain?

The answer is always: pizza. And sushi. Not at the same time, though it does sound like something I’d try make work.

________________________

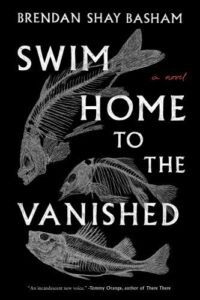

Swim Home to the Vanished by Brendan Shay Basham is available from Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Brendan Shay Basham

Brendan Shay Basham (Diné) is a fiction writer, poet, educator, and former chef, born in Alaska and raised in Northern Arizona. He received his MFA from the Institute of American Indian Arts, and a BA in Liberal Arts from The Evergreen State College. His work has appeared in Puerto del Sol, Santa Fe Literary Review, Yellow Medicine Review, and Juked, among other publications. He is a recipient of Poetry Northwest’s inaugural James Welch Prize for Indigenous writers, the Ucross Foundation’s first Fellowship for Native American Writers, and fellowships from the Truman Capote Literary Trust, Tin House, and Writing By Writers. Basham lives in Baltimore, where he runs a make-believe café with his wife and dog.