Breaking the Family Cycle of Male Rage

Confronting My Father's Flawed Definition of Masculinity

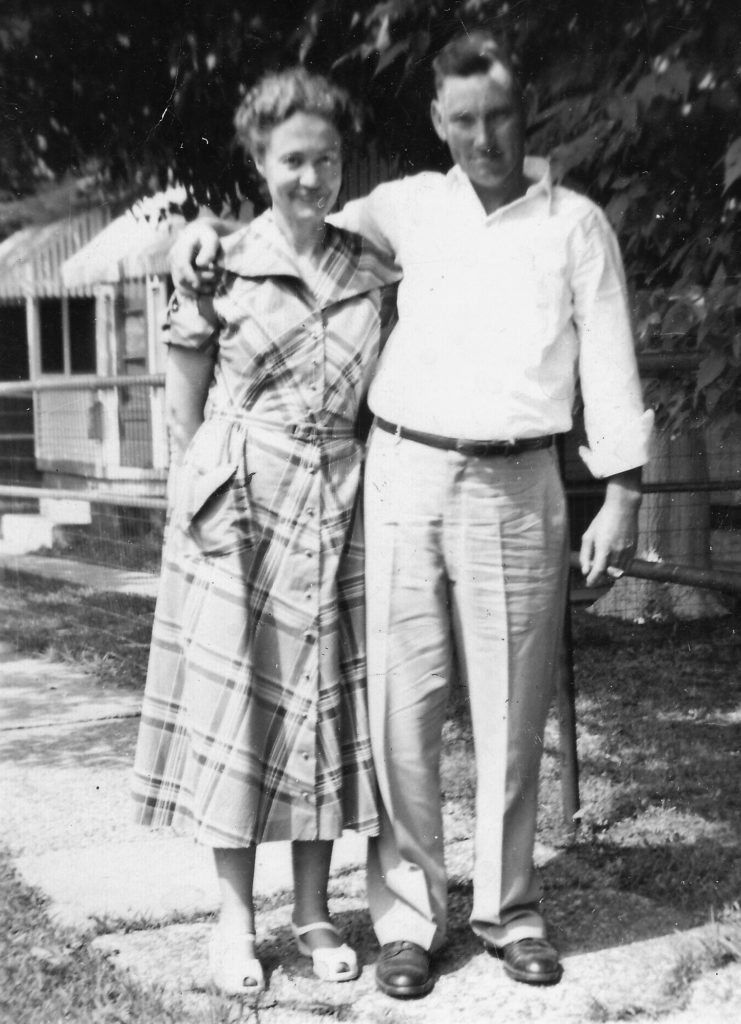

I have only one photograph of my father and mother from their courting days. They’re standing on the sidewalk in front of someone’s house, and my father has his arm draped over my mother’s shoulders, a cigar stub clamped between his fingers. The photograph fascinates me because this is the only image I have of his adult hands. In November of 1956, when I was barely a year old, he lost both of them in a farming accident and wore prostheses the rest of his life. To gaze upon his hands in this photograph is to mourn the event to come and to wonder how he might have been a different man, had the accident never happened.

It seems I’m always writing from the moment that severed me from him—that moment in the cornfield when the shucking box on his picker clogged. Instead of shutting down the power take-off as he should have done, he tried to clear the box while the snapping rollers were still turning, and they caught first one hand, then the other. Our lives separated into before and after. He became an angry man. I grew up, always on guard, always afraid I’d do something to provoke him. But at the same time, I wanted to please him, and that desire still shadows my relationships with other men. All my life, I’ve wanted their approval: the basketball coach who gripped my head between his big hands one night at practice so I’d have no choice but to look into his eyes while he gave me a tongue-lashing for a mistake during a drill, the forceful Church of Christ minister who terrified me with fire and brimstone, older colleagues who have risen to a certain prestige—any man, really, who makes me feel I’ll never really belong to whatever fraternity it is that men aspire to join.

My father did his best to initiate me into that alliance, and for a while, it worked. I followed the pattern of masculinity he modeled. When I was in high school, a girlfriend left me for another boy, so I put him down with a single punch. My show of force did nothing to win her back, but at least for a while, it brought me closer to my father. That evening around our supper table, when I told my parents what I’d done, my mother was mortified. My father pretended to disapprove, but I could tell by the way he kept coming back to the story, asking for more details, that he was secretly pleased.

I felt—and still feel, to some degree—that I was never meant to be his child. I was a sensitive sort who had no interest in farm work; I’d rather be reading a book than riding a tractor. The only thing that connected us was my athletic ability—we should have been able to enjoy that, but there were times when his temper robbed me of even that pleasure. I still remember him berating my junior high basketball coach because he hadn’t voted for me for the league’s annual sportsmanship award. My father’s anger embarrassed me, but I didn’t have the nerve to tell him I wished he’d accepted the fact and never said a word. At the same time, I wished I could be as bold as he was. I longed for the two of us to be closer, so united in our rage and our determination that no one would ever take advantage of us.

“Men teach one another, generation by generation, to not back down, to win, to be on guard for whatever force might threaten them.”

My father was a man of a certain time (the early 1950s) and place (rural southeastern Illinois), and because of that, he had assumptions about power and his right to use it. His message to me was clear: I was a man, and a man got his way through the use of force. I’ve spent years and years unlearning this behavior, but I still sometimes hear him in my voice. I cringe at the moments when his influence rises up in me and I find myself speaking or acting in a way that reflects his definition of masculinity. Thirty-six years after his death, he still lives inside me. I’ve tried to keep the best parts of him—his determination, his generosity—while rejecting his anger and violence. If I’m completely honest, however, I have to admit that I’ll always be that little boy desperate for his approval and sometimes, my worst times, I let that desire determine my words and deeds in ways that do harm to others, and to myself. But I’m heartened by the knowledge that we can confront the influences that threaten us, the pressures we didn’t ask to have; we can control them, transform them, and by so doing, be transformed.

In my most recent collection, The Mutual UFO Network, I wanted to explore what causes male anger and entitlement, and the transformative potential of confronting it. The boys and men who populate my stories long for connection: the son in the title story, who aches for his father even as he distances himself from that father’s deceit; the eccentric man who wants his neighbors’ friendship; the man who seeks solace in the company of a stronger man in the aftermath of his wife’s abduction; the man who, weary of the humiliating story his wife can’t stop telling about him, lets his desire to please a stranger carry them to a dangerous situation; the man who, frustrated by his brother’s tolerance of a situation that brings shame to the family, pushes the issue to the extreme, changing everyone’s lives forever. When I wrote these stories, I entered the hearts and minds of men and boys like my father and me. As I followed these characters, I felt the loss, or the fear of loss, that resides in all of them. Men teach one another, generation by generation, to not back down, to win, to be on guard for whatever force might threaten them. As a result, they slip further and further from the boys they were—open-hearted and compliant—before they were initiated into the intractable and limiting world of men.

Every story I tell leads back to that instant in the cornfield when my father’s hands hovered above that shucking box. Everything I write comes from the loss I can’t stop us from suffering. I can’t give our narrative a different end, nor can I stop myself from trying. I’m caught forever in that space between loss and desire, that place where the aching bumps up against the possibility of redemption. My characters live in that space. Maybe we all live in that space. As a writer, I have no choice but to delve into it, to feel the effect of my father’s accident, to spend my life writing stories to try to save him from his anger, to live in those moments when anything might be possible—even love.

I want to believe we all can free ourselves from the chains our culture’s perception of masculinity wraps around us, the self-imposed shackles that lock us into a way of seeing everyone and everything as a threat. To break those bonds requires an awareness of the sources and the consequences of one’s own actions, along with the courage to trust in a life lived with kindness and generosity. We have to know our greatest threats come from ourselves so we can loosen the stranglehold of our insecurities and fears and live better-considered lives steeped in empathy and acceptance.

Lee Martin

Lee Martin is the author of The Mutual UFO Network. His novels are Late One Night (Dzanc, 2015); The Bright Forever, a finalist for the 2006 Pulitzer Prize in Fiction; River of Heaven; Quakertown; and Break the Skin. He has also published three memoirs, From Our House, Turning Bones, and Such a Life. His first book was the short story collection, The Least You Need to Know. His fiction and nonfiction have appeared in such places as Harper’s, Ms., Creative Nonfiction, The Georgia Review, The Kenyon Review, Fourth Genre, River Teeth, The Southern Review, Prairie Schooner, and Glimmer Train. He is the winner of the Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Ohio Arts Council. He teaches in the MFA Program at The Ohio State University, where he is a College of Arts and Sciences Distinguished Professor of English and a past winner of the Alumni Award for Distinguished Teaching.