Break Everything and Begin Again: On Fragmentation as a Form

Sarah Haas Considers the Ways We Give Shape to Ideas

Maybe it is broken, but hasn’t it technically just entered a different form of existence?

*

Imagine a fragmenting starfish, a piece of itself breaking apart from itself, its genetic material encased in a limb now detached from the body so that it can become a new body.

Fragmentation: a form of reproduction.

Is this how I mean to describe my writing?

I don’t know.

But I use the word “fragmentation” anyway, not because the term is self-evident, but because I think it an effective means of communication, that you will know what I mean when I say it.

“Fragmentation.”

A word like a logo.

A form of marketing.

A form of propaganda.

The opposite of the literature I’ve set out to create.

My fear is that this, the moment I’m trying to describe my writing, is the moment I stop being a writer, the moment I start taking my language for granted.

*

My son, now eight months old, is at that point where his babbling is falling into meaning.

The difference between saying “mama” and pointing at the dog and saying “mama” while reaching his arms out for me.

How marvelous it is to say something for the very first time.

And then to say something and really mean it.

Especially considering the alternative is to say nothing at all.

From Lydia Davis’s essay, “Form as a response to doubt”:

To work deliberately in the form of the fragment can be seen as stopping or appearing to stop a work closer, in the process, to what Blanchot would call the origin of writing, the center rather than the sphere. It may be seen as a formal integration, an integration into the form itself, of a question about the process of writing.

“It can be seen as a response to the philosophical problem of seeing the written thing replace the subject of the writing. If we catch only a little of our subject, or only badly, clumsily, incoherently, perhaps we have not destroyed it. We have written about it, written it, and allowed it to live on at the same time, allowed it to live on in our ellipses, our silences.

*

Below is an image of my redacted work; each sentence, or part of a sentence, occupying its own line.

A hundred false starts and then, this:

I had heard writing described as thinking on the page.

This, the first time I actually, I did.

The shape of my thoughts honestly observed.

Including the not thinking, when the thinking stopped, and where.

I didn’t have to stand at a distance to see all of the writing’s flaws, all of its assumptions and prejudices and contradictions laid bare.

It was the first time I wrote and was absolutely certain I was being sincere.

*

This form, or should I say strategy, was inspired in part by Verlyn Klinkenborg’s Several Short Sentences About Writing, also written with each sentence on its own line.

He writes:

What you don’t know about writing is also a form of knowledge, though much harder to grasp.

Try to discern the shape of what you don’t know and why you don’t know it,

Whenever you get a glimpse of your ignorance,

Don’t fear it or be embarrassed by it.

Acknowledge it.

What you don’t know and why you don’t know it are information, too.”

Klinkenborg’s searching technique was likely inspired by David Markson’s post-modern marvel Wittgenstein’s Mistress, also written with each sentence on its own line. Here’s an excerpt, as curated by David Foster Wallace, in which the narrator, Kate, who assumes herself to be the last living person, examines a painting:

There is nobody at the window in the painting of the house, by the way.

I have now concluded that what I believed to be a person is a shadow.

If it is not a shadow, it is perhaps a curtain.

As a matter of fact it could actually be nothing more than an attempt to imply depths within the room.

Although in a manner of speaking all that is really in the window is burnt sienna pigment. And some yellow ochre.

In fact there is no window either, in that same manner of speaking, but only shape.

Unless of course I subsequently become convinced that there is somebody at the window all over again.

I have but that badly.

A stripping away of what she thinks she knows until language becomes a hindrance, until all that remains of shadow is shape.

*

I like to think of language as a container, that which gives liquid shape, a vessel through which our eyes and voice will form so as to guide our thinking in return.

*

I like to think of language as a glorified gutter.

*

I like to think of text and the page as a relief: the rising up of one surface and the recession of the other.

The writing of one story also the not writing of another.

Its absence allowed.

To be.

(A kind of presence.)

*

I like to think of story as a timeline.

A few instances rising up to assert themselves as emphatic facts of history, even if we know better, that history is only ever a form of biography.

*

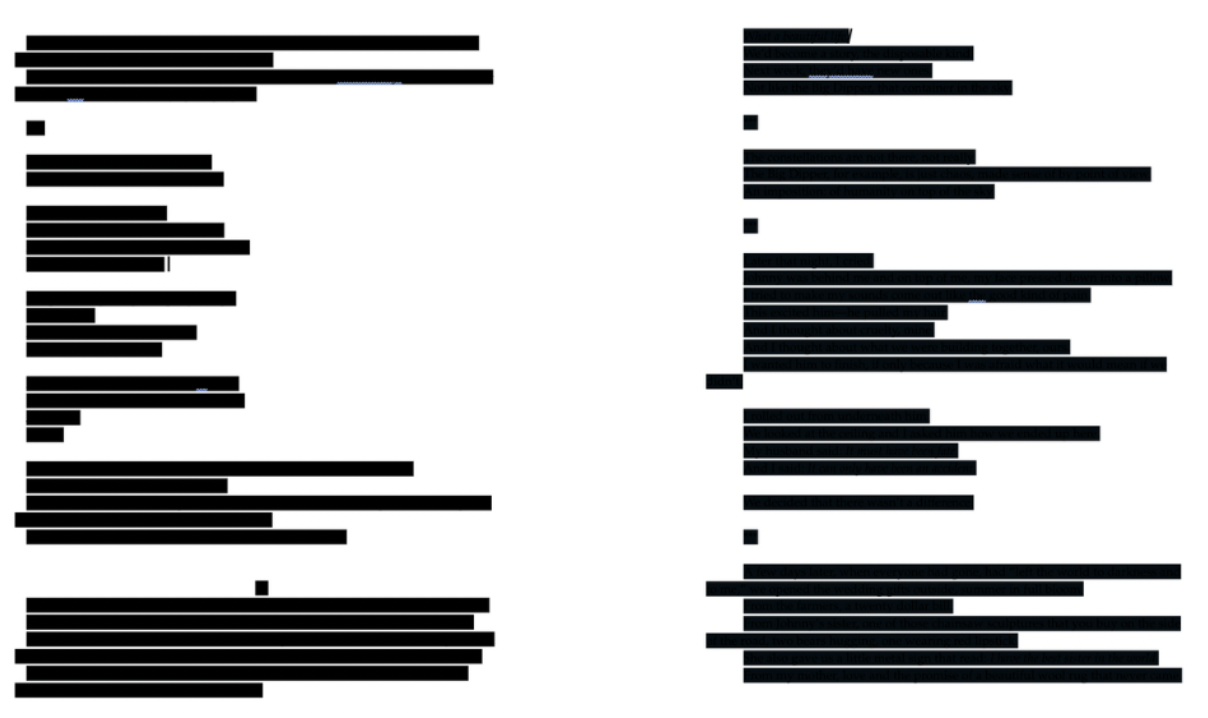

Today our timeline, or should I say mine, begins with Sappho, in 610 BC, her poems so unlikely.

She, The Poetess, a lesbian on the outside of the patriarchy looking in, her work a triumph in spite of her time, her work that would be relegated to time, her work that would be nearly lost to time, her parchment now reduced to this tattered thing.

Sapphos’ poem “An Old Age” (lines 9-20). Papyrus from 3rd century B.C. The exhibit from Altes Museum Berlin.

Sapphos’ poem “An Old Age” (lines 9-20). Papyrus from 3rd century B.C. The exhibit from Altes Museum Berlin.

Pictured above is Sappho’s “Tithonus” poem, or part of it, as recovered from one of three distinct archeological digs.

Now, scholars say, the poem is almost complete, a state of almost completeness that perfectly resounds the poem’s content, the story of Tithonos who was granted immortality but not eternal youth, who grew older and older still, a tattered thing talking and talking and talking, droning on though thread-bare.

Here is part of Anne Carson’s translation of Sappho’s rendition, “The Beat Goes On.”

A human being without old age is not a possibility.

There is the story of Tithonus, loved by Dawn with her arms of roses

and she carried him off to the ends of the earth

when he was beautiful and young. Even so was he gripped

by white old age. He still has his deathless wife.

The part of the story that Sappho doesn’t tell, the mercy that Zeus takes upon Tithonos when he turns him into a grasshopper, chirping through the night.

Or maybe she did tell that part of the story but it’s been lost to the part of the parchment that’s disappeared.

Parchment has an average half life of thirty years.

Ink hastens the decay of paper.

Words that literally consume themselves.

If put in a landfill, the piece of paper on which I drafted this essay would decompose beyond recognition in three to six weeks.

*

One thousand years after Sappho, Sei Shōnagon wrote her poetically parsed essays in The Pillow Book.

Here is her “List of Things that Have Lost Their Power”:

A large boat which is high and dry in a creek at ebb-tide.

A woman who has taken off her false locks to comb the short hair that remains.

A large tree that has been blown down in a gale and lies on its side with its roots in the air.

The retreating figure of a sumo wrestler who has been defeated in a match.

A man of no importance reprimanding an attendant.

An old man who removes his hat, uncovering his scanty top-knot.

A woman, who is angry with her husband about some trifling matter, leaves home and goes somewhere to hide. She is certain that he will rush about looking for her; but he does nothing of the kind and shows the most infuriating indifference. Since she cannot stay away forever, she swallows her pride and returns.”

The form of the list, a cousin of “fragmentation,” a collection of disconnected things brought together by the page on which they appear, or the title which precedes and so collects them.

The list like a body made up of parts, a container for the soul.

But what is a soul?

An impossible question!

Although perhaps the list’s form gives us a clue, its items salvaged from the chaos of the whole and so granted constituency to the partial, the soul the connective tissue amassing a new whole, the non-thing that makes the person worth more than the sum of its parts (and yes, I recognize that this is also the formula for capitalistic profit).

*

I want to linger over Shōnagon’s final image, on the powerless woman returned to her husband, an image so encompassing it swallows all the rest.

Every time I read that final line, I am compelled to read the list again, a reiterating cycle, the powerless woman rebirthing her progenitors, folding all instances of faded power into her own meaningful story.

The epitome of what an image can do.

Because an image is the vehicle by which every artist becomes a mother, not like a god but like a womb that creates the world it then inhabits, the importance of the self reconfiguring to accommodate the needs of its creation—the writer, now the mother, eventually the crone—a gendered interplay that lies at the heart of the fragmented form, which is not to say that the form is feminine or sexed at all, but that it is inherently ambiguous, a form of play with the self.

The same as the writer’s play with content and form.

There are so many ways for a self to be.

But, as any mother and maker knows, there are as many ways for a self to die for, in order to birth, one must first confront at least the possibility of death, specifically their own, and then their child’s.

*

And so it was that 700 years after Sei Shõnagon, and half a world away, the Frenchman Stephane Mallarmé, known as a fusionist for his combination of poetry and literature, explored the relationship between content and form, life and death, the arrangement of language and space on the page.

His “A Tomb for Anatole” was published in 1961, 63 years after the author’s death.

It comprises 202 texts of an unfinished epic poem written after the loss of his eight-year-old son.

1.

child sprung from

The two of us—showing

Us our ideal, the way

—Ours! Father

And mother who

Sadly existing

Survive him as

The two extremes—

Badly coupled in him

And sundered

—From whence his death—o—

Blitterating this little child “self”

2.

Better

As if he (when)

Still were—

Whatever they may have been,

Of epithets

Worthy—etc.

The hours when

You were and

Were not

3.

Sick in

Springtime

Dead in fall

It is the sun

_____________

The wave

Idea the cough

“Fragmentary or Unfinished,” Lydia Davis describes the inarticulateness of these forms as being “the most credible expression of grief.”

I’m tempted to agree, and so I wonder what it is that makes an expression “credible.”

I think of the expression of our lives we all most readily believe because we must: time.

*

I think of the morbid inscriptions on sundials, for example: Sine sole sileo.

Without the sun I fall silent.

The impossibility of describing something that isn’t anymore.

*

I think of what Annie Ernaux recently said in The Paris Review, that, for her: “words that are set down on paper to capture the thoughts and sensations of any given moment are as irreversible as time—are time itself.”

*

I think of a conversation I once had with my mentor Sarah Manguso, when I asked if her concision and form had anything to do with social justice.

Firmly, she answered yes, and then she cited time.

And then the inevitability of death.

She said something like:

This could be the last sentence I write.

This could be the last sentence you read.

So how ought the writer deal with time?

To long for its capability, our freedom.

And then to admit its constraint.

So let us consider the time of those most constrained by time.

Let us consider the time of the exiled, the time of the imprisoned, the time of the scapegoated, the time of the mother, the time of the consumer, the time of the oppressed.

*

Let us begin with the time of the exiled, of Edmond Jabés, an Egyptian Jew exiled in Paris who asked what it was to resist:

“What is subversion?” he wondered in his unexpected book.

“Subversion is the very moment of writing: the very moment of death.”

“If the word enlightens, silence does not obscure: it regenerates.”

“Nothingness, our eternal place of exile, the exile of Place.”

Perhaps to become free, we must sublimate.

To resist is to allow nothing to exist, too.

*

Let us consider the time of the scapegoated, the time of Ann Quinn, a British Jew who killed herself in 1973, at the age of 37, by walking into the sea.

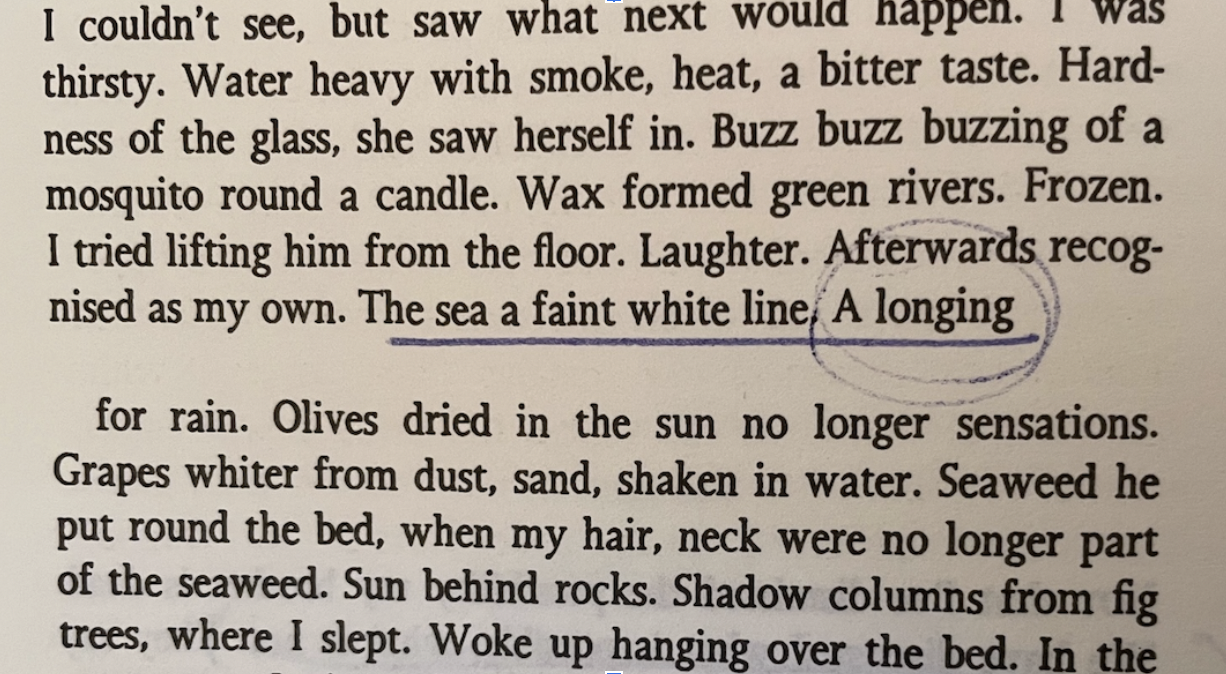

[How best to represent? Text (the perfect contextual contribution)? Or picture (to showcase form)?]

“…the sea a faint line. A longing

For rain. …”

In the introduction to Passages, the book in which this haunted line appears, Claire Louise Bennett describes the form of Quinn’s work as fragmented, which she then characterizes further: “her form reflects day-to-day life, precarious and haphazard, fragmented and beyond your control.”

I love to think of “fragmentation” that way, as of life, and so as an always reaching for what is beyond.

How brave it can be to allow the fortitude of every presence to suggest the limitlessness of absence, to write in pursuit of the endlessly recessive real.

Buried in the catalogs of Passages is Quinn’s direct confrontation with form, the same as her admission of the absurd.

Absurd Form

Orig. deaf formal

mute formaldehyde

geography—earth+metron formality

measure formication

writing about earth formidable

irrational

Perhaps to capture the real, we must abide the absurd and irrational.

*

Let us consider the time of the imprisoned, of Reginald Dwayne Betts, as in his 2016 The Yale Law Journal essay, “Only once I thought about suicide,” which tells of his time in solitary confinement:

But before I could speak, he slammed me against a brick wall. Handcuffed me. Dragged me to a cell in the hole for assaulting an officer. They tossed me in a cell with a door so thick that no sound escaped. I was sixteen years old. Each morning they took my mattress from me so that I could not sleep during the day. How do I explain this? Each day, I lost a little bit of what made me want to be free. I’ve never told this story. Those were the longest days of my sentence. One afternoon, in a fit of panic, I slammed my right fist against the wall. I fractured my pinky. I thought about suicide. I almost disappeared.

Betts’s description highlights the spatial aspects of the punishment that is meant to suppress speech as a proxy for recognized existence: “before I could speak, he slammed me against a brick wall,” “a door so thick that no sound escaped,” “I almost disappeared.”

Instead, and in spite of, he persisted, surviving every day until he was released, making his way through law school to earn a Yale Law degree in 2016, the year in which his essay was published in the school’s prestigious journal where his essay appears formally distinct from the traditional academic pieces beside it.

Written in six sections and in paragraphs of various lengths that are often only obscurely connected, Betts’s form exhibits a precarious status of free speech, his “fragmentation” a refusal of prolixity that transports the physical restraints of incarceration into the theoretical realm that engenders it so as to challenge its institutional power.

*

Let us consider the time of the mother, of Rachel Zucker, from her genreless book Sound Machine, a book written from her child’s bedroom while he sleeps:

My presence makes this a room-with-mother where sleep is possible.

The room suffers me but does not cause me suffering. Mostly.

Not quite prisoner. Not quite Warden. Mother.

His fear teaches me.

Assuage is how I put my time in.

To assuage: what an odd version of commitment, the mother’s fecundity giving way to such a barren version of time that is always accounted for yet never productive.

And so the mother who, like Zucker, is also a writer, laments that they are, for a time, no longer a writer but one who’s time must abide the dependent other.

“To write prose requires that I shut out the world,” which is, for the mother, an impossible proposition.

To shut out the world the same as to withhold care the same as the world collapsing and then ceasing to be.

Zucker turns to prose’s prolific male writers as exemplars.

Supposedly, Jonathan Franzen wrote The Corrections blind-folded in his basement. Or was that David Foster Wallace writing Girl with Curious Hair?

Jim Galvin said, “Writing prose is just typing.” He said it right after I’d told him how much I liked his book The Meadow.

No big deal, these men opine, as if to say that to write is simple, just inhabit the timelessness of creation.

Ironic, isn’t it?

Seeing as how it’s the mother alone who knows what this means, the timelessness with which she conspired to bring the child into being and with whose being she now must constantly contend.

So the mother writes like Zucker, in a rocking chair, in the dim of a child’s room, in a notebook or with one hand on a phone, stealing time and attention, one sentence at a time, knowing all the while that there isn’t a market for her work, that it won’t help to pay the bills or pay for college, that her uncategorizable writing is just a desperate call from out of the dark into an even greater darkness still.

*

Let us consider the time of the worker, with the practicality of the clock’s productive march, as in this tweet from poet Chen Chen: “Always thinking of Anne Boyer’s response to an interview about the biggest hurdle to her writing practice.”

Her response: “Capitalism, which continues to devour the living world that we need as our home and to consume the hours of everyone’s lives for the profit of the very few, setting people against each other for the mere preservation of life and pressurizing gendered and racialized forms of oppression. There’s no writing without time, without the air to breathe and potable water, without a body and earth that supports life, without each other.”

So what does Boyer the poet and mother and worker do about this hurdle?

What do we do?

Boyer’s answer seems to lie in the spectrum of refusal, as formally available to the writer in negative space.

From Anne Boyer’s essay “No”:

Saying nothing is a preliminary method of no. To practice unspeaking is to practice being unbending: more so in a crowd. Cicero wrote “cum tacent, clament”—“in silence they clamor”—and he was right: only a loudmouth would mistake silence for agreement. Silence is as often conspiracy as it is consent. A room of otherwise lively people saying nothing, staring at a figure of authority, is silence as the inchoate of a now-initiated we won’t.

And yet the collective we must work, are always working, or are subsuming to the palliative of consumption, our cyclical days moving in circles like hands around a clock we no longer know how to read because it takes too much time that we don’t have time another thing we don’t have but borrow and so are indebted to as we borrow against our own lives for school for housing for entertainment our most precious moments gamified and commodified in photo albums that behave like shopping malls because that moment that made us feel like enough has turned out to pale in comparison is empty and yet we persist except for those moments when we have the resolve to say no and so make a little time to keep for ourselves.

*

Finally, let us consider the time of those from whom power and time is routinely taken and rarely restored, the time of the systematically oppressed, the time of James Hannaham’s Pilot Impostor, his book that uses the form of Portuguese colonialist poet Fernando Pessoa to posit the freedom of further possibilities.

Here is his genreless section “Food Chain,” in its entirety:

Science keeps discovering that subjects never before thought to have significant consciousness or the ability to think actually do. In no particular order: crows, sunflowers, Black people. Researchers presume that their subjects cannot know, experience, interpret the world, or understand they will someday die. This assumption pays the human salary, allowing us to eat, torture, and profit from any entity we deem less conscious than ourselves.

The Portuguese began the Atlantic slave trade in the 1500s and, somewhere along the way, began to justify the practice with an ethnocentric bias against sub-Saharan Africans already available to anyone.

Five hundred years later, the vegetarian protests, a forkful of greens at her open mouth. Is this not okay? Is a salad sentient?

He ends with a joke, or at least I think it’s a joke; I laughed, but just a little, and only to myself.

I turned the page.

A picture of a mind.

Three pictures of Portuguese tiles.

I turned the page.

A section on “Seeing and Thinking” that turns the might-be-joke into a definitely-was personal assault as Hanaham stands-in for the salad that was standing in for him because none of this is a hypothetical thought experiment but the other way around.

I turn the page.

More tiles.

Another picture of a mind.

At what point, I wonder, did the might-be-joke stop being funny?

Did one thought segue into the subsequent thought that rendered my own laughter cruel?

In the awkward chamber of my own fading laughter I find myself indebted to Hanaham’s wide open form for allowing me to linger on the joke which is always a crack in the thin surface that is meaning what we say, a revelation, of truth and/or shame.

*

To be sure, the fragmented form, or whatever it’s called, has its critics.

Let us consider them too.

To begin, here’s this tweet from Joyce Carol Oates:

Strange to have come of age reading great novels of ambition, substance, & imagination (Doestoevsky, Woolf, Joyce, Faulkner) & now find yourself praised & acclaimed for wan little husks of “auto fiction” with space between paragraphs to make the book seem longer…

Maybe she is right.

*

And here’s this bit of thinking from Lauren Oyler, in her auto-fictional novel Fake Accounts in which the unnamed narrator listens to a literary interview podcast (which, rumor has it, is in reference to David Naimon’s Between the Covers, when he was in conversation with novelist Jenny Offill about her so-called fragmented book The Department of Speculation):

The author said she thought having children contributed to the form and style of her books, written in stolen moments, necessarily short sections, simple, aphoristic sentences, more of an essay than a novel at times. Lots of women were writing fragmented books like this now, the interviewer pointed out. Having read several because they were easy to finish, I couldn’t help but object: this trendy style was melodramatic, insinuating utmost meaning where there was only hollow prose, and in its attempts to reflect the world as a sequence of distinct and clearly formed ideas, it ran counter to how reality actually worked. Especially, I had to assume, if you had a baby, which is a purposeful experience (don’t let it die) but also chaotic (it might die). Since the interviewer and the author agreed there was something distinctly feminine about this style, I felt guilty admitting it, but I saw no other choice: I did not like the style.

It’s worth pointing out that Oyler’s narrator limits her critique to the realm of taste which is the basis of her opinion that nonetheless seeks to demean large swaths of prose in sweeping and ill-intended generalizations.

(I tend not to give a lot of time or credit to such unkindnesses.)

And yet, I recognize Oyler as one of the great living critics; maybe she is right.

Maybe fragmentation does run counter to reality which really is an infinite and ongoing whole, the same as Italo Calvino’s “encyclopedic impulse,” Goethe’s “novel about the universe,”* David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, or Leo Tolstoy’s 570,000-word War & Peace, his attempt to consider and explain the narrative that is humanity which is the high calling of art.

In Part 4, he writes “The reality of our lives is of continuous movement, we have created arbitrary measurements to break up the whole.”

Tolstoy’s long-form work, then, presumes to present an alternative world view to the fragment, which he also inadvertently argues against, writing that by “taking smaller and smaller units of measurement we only approach the solution and never reach it.”

It’s that grade-school problem of half-lives, that a substance, like Sappho’s parchment, will never truly disappear.

Or, put another way, if we always go half the distance to the door, how can the threshold ever be crossed?

It is this very problem, imposed by units and its capitalist cousin, that gives us the Western standard of beauty as based on the golden ratio that produces the golden spiral, sharing the form of the Hegelian dialectic that reaches always up, up, up for the impossible grasp.

After writing War & Peace Tolstoy came up with a solution to this, his infinite quandary: he became a pacifist, advocating for peace, by which he meant nothing, or so I gather by reading between his many lines: “Man’s intolerance for nothing is why peace would never exist.”

In pursuit of nothing, he gave up his wealth and possessions to adopt the life of a peasant, living penniless until his death at the age of 82.

His last words “but the peasants, how do the peasants die?”

But the annals of history are somewhat dissatisfied with that ending, preferring to remember the words he spoke the night before:

We all reveal…

Our manifestations…

This manifestation is over…

That is all.

*

It seems to me we are destined to have to contend with the negative space, with nothing.

But how?

Do we pursue the truth of the fragmented, or of the irrefragable?

Do we admit the terms of our warring conditions, or do we posit peace?

Do we despair, or do we hope?

This questioning, this constant wavering, is where the real work of writing lies.

*

Kiese Laymon’s inquires into the nature of the writer’s labor in his expansive criticism of “white space” by which he means not just the space between words or paragraphs but the space in the margins, too, the totality of that generously creative space of “subtext and marginalia”:

I think if you can invite readers that way through the use of subtext slash marginalia, you can get them to feel like this book is mine. … Part of what they think you’ve shown them is universality. But what you’ve really done is you’ve invited them into a white space with you to embody. I’m not being spiritual or weird or anything. I literally believe that.

But you create subtext. There are many ways. One way, you have to overwrite, and you have to take some of the stuff out. Meaning that you can’t be precious about it. Precious writers do not have subtext—they have omission. Omission is different. Once you realize that this might be my next best graph in the book, but taking this graph out and having readers wonder about the relationship between graph one and graph three, it might do the work for me. Sometimes I just think that work is underrated, but also we don’t really know how to talk about it publicly. But the margins, the margins, fam, the margins—that’s where the work is.

Laymon’s pervasive call to heed the white space, carefully and thoroughly, is a call, I think, to do the same with our lives.

It recalls Hamlet’s infamous question: To be, or not to be.

But Laymon warns us not to be overly precious about this binary, our existence, and so against omission, echoing William Gass’s warning against the silence of the “utterly unuttered”: “To go wordless, is to go without a soul to shit with. It is but to go.”

An experience without rumination; is there happiness in such a simple infinitive?

For me, and I imagine for most writers and artists, the answer is a hearty no—echoing Plato, the life considered is the life well lived—even if the consideration never makes it to the page, is struck-through and then deleted, relegated to exist in the negative space in perpetuity.

Even as I (we) suffer the consequence of this choice to write.

It’s a fact: by writing, I separate myself from living.

And yet: I write.

Such a simple infinitive.

*

But why?

Why do I (we) write?

*

In 2019, painter Amy Sillman curated an exhibit at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, entitled “The Shape of Shape.”

In an accompanying essay she writes:

Basically everything in the world is a shape.

Shapes are how you make distinctions, get the lay of the land, or even tell time.

*

Why I write: to make distinctions.

To get the lay of the land.

To tell time.

*

Of visual art, Sillman asks what it would look like “if shape prevailed over all over considerations.”

I wonder the same thing about writing.

What if shape, i.e. form, was paramount?

What if what is said doesn’t matter as much as how, a sentence not a unit but a line?

*

Sillman posits the difference between content and form as the difference between “composition” and “construction,” where “to compose is to re-inscribe the previous values of the bourgeois class” and “to construct is the way to make a new society.”

Sentences like two-by-fours, a writer with a hard hat, an architecture of hope against a tendency to despair.

*

And now I want to tell you a story, about the first time my baby, then still a fetus, felt real.

I was at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, having just taken a cross country train trip by myself.

The first exhibit I visited was of the drawings of Giacometti, the first thing on the wall not art but text, a quote from Sartre:

“One must begin from scratch.”

(Some lines from that same essay that weren’t on the wall:

He breaks everything, and begins all over again.

And: Always between nothingness and being.)

The rest of the exhibit was a series of line drawings that seemed to begin at the center of the subject and spiral out, Giacometti’s great achievement his genuine searching and then inevitable arrival at the shape of one thing or person after the next.

I left the exhibit but carried his methodology with me, walking through the rest of that museum and then another noticing outlines.

On Grecian urns and Persian prints and medieval still lives and Biblical scenes and Egyptian engravings.

On Redon’s and Picasso’s and Wilde’s.

On Thiebald’s cup of coffee, “see the edges of the edges,” he advised.

On the canvases of Prunella Clough who said of her work, simply: “I want to say a small thing edgily.”

(What else is writing? Art? But a small thing at the edge of?)

I stood up close to an Alice Neel, my belly inches from the belly of one of her pregnant women.

The edges of our edges creeping ever closer.

My feet hurt.

Looking for a quick exit from the museum, I entered a room housing one lone projector pulsing off-white light against a white wall.

I stood there, watching, expecting an image to emerge.

I waited.

Nothing happened.

As I walked past I saw my own shadow, the bulge at my center, emerging, the shape of my body turning into ours.

A beginning.

Like the one I’m confronting now, even though I’m nearing the end of this essay, stalling, not knowing what to write next, the taunting of the blinking cursor which is not really blinking at all, but a line that is here, and then not, and then here, and then gone.

How we begin, over and over again.

Where that fundamental risk: to live or to die, collides with the fundamental risk of writing: to propagandize or to create.

How I began.

Have I learned anything at all?

For a few days, I cannot write.

Instead, I watch my son, crawling on the concrete, seeing his own shadow for the very first time.

He reaches out to touch it but touches only the warm ground, a disappearance.

From a distance, I extend my arm so that my shadow intersects with his, once again a shadow becoming ours.

Again he reaches to touch the gray shape on the ground, a reunion.

Proof that I, we, exist.

Why I write.

Sarah Haas

Sarah Hass's work has appeared or is forthcoming in Literary Hub, Longreads, The Rumpus, Adroit Journal, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Entropy, Rain Taxi, and Tupelo Quarterly, among others. She has written columns for various Colorado-based publications, including Boulder Weekly, where she also freelanced as a features and arts & culture journalist.