You’re fourteen. You don’t like these slacks, but someone once said you looked awesome in them and that’s enough to make you put them on today, so in the mirror there’s at least an idea, if not a whole person. When you were little you said flacks and everyone laughed, but there was tenderness in that laughter because it contained the idea that the mistake would stop when you were older. Now you’re fourteen, standing in awesome slacks and looking at an ungainly body in the mirror. The mirror is small, its edges mean your legs below the knee and one shoulder are cut off. In the mirror is a mutilated body, and inside that body is you. The contradictions in your reflection are more painful than the overtight slacks. You bleed hot, thick blood out of too small a body. Between the stocky legs of a little furled girl you carry a sharp bush that no one has yet seen. Not even mum, not even a doctor. You’re afraid of your bush because you’re convinced other little girls don’t have one. They’re probably smooth down there, there must be something wrong with you. All the others are taller than you and almost all have breasts. Their fingers aren’t little girls’ fingers any more, they hold pencils as though they were cigarettes, they sway when they walk, they know how to pluck their eyebrows. You once tried to fix yours, but you overdid it and dad was furious. He asked whether you wanted to be a whore when you grew up. You shook your head. You stared at your plate, mum and your brother said nothing, the restaurant was full of little girls with perfect eyebrows. They’re not going to be whores, you thought. They haven’t got bushes down there or inside them. They’re smooth. But eyebrows grow and now in the mirror yours are huge again. You try flattening them with your fingers and then you see your nails, cut to the quick, because you play the guitar and you’re not allowed to have nails. Once you put polish on them and dad was furious. He said he knew a lot about the world and a girl who used nail polish at fourteen would be pregnant by sixteen. That’s why your nails are colourless and cut off so that you’re constantly aware of them. That pain is the pain of the edge, where the flesh stops and blood begins. You carry that pain in your fingers all the time, whatever you touch. You touched your lips, they’re rough and peeling. Mum gave you lip balm and said you should carry it with you always as chewed lips aren’t nice. That’s because you chew them and press them together whenever anyone looks at you. And someone’s always looking at you: teachers, girlfriends, boys, older boys, the woman next door, mum, dad. You can always be sure of other people’s eyes on you wherever you are, that’s why you’ll always munch on your lips. It’s easier than talking. Cooking, you have to learn: talk less or your lunch will burn, your gran once told you when you were making biscuits together. Gran had cracked lips as well, she didn’t talk much either, but her breasts were enormous above the firm knot of her faded apron. You wouldn’t have been able to carry them, you’re sure they’d break your back. You’re afraid of those breasts of gran’s and of those few black hairs on her small, protruding chin. There’s no time for chatter, lunch must be made, she says brightly, opening the oven. Her breasts hang almost to its shelves. When you were little, you thought the oven might swallow up gran and her big breasts. You think about that now as you look at your tight sweat-shirt with a slogan you don’t understand. Cool, the prettiest little girl in the class said when you came to school in that sweatshirt last week. No, she’s not a little girl, but a young lady. She’s already a young lady. You’d like to have her hair: long and straight, without a tiresome kink above her forehead. When you were at the photographer’s, mum licked her fingers and yanked that kink so hard it gave you a headache. That was for a family photo, that pain in your skull. You feel it now every time you look at the photo. You have the feeling you can see mum’s spit in your hair as well. You once washed your hair with something called color-shampoo and then on your summer holiday you sought out the sun to catch the red sparks on your head. You wanted to have something to show that was yours and wasn’t ordinary, boring. But that didn’t last long because you were afraid dad would notice. You washed your hair with hot water every morning so as to kill the red colour before he saw it. The heat scalded the crown of your head, but you put up with it because even the weakest ray of sun would have been enough to ruin yet another family mealtime. Now you’re here, in the mirror, ordinary again, hair brown as a dried chestnut again, with overlarge eyebrows and a kink in your hair and cracked lips. Your awesome slacks and your cool sweatshirt are unobtrusive enough to be taken out of this small room. You pass mum in the kitchen and dad on the couch and go outside. Because it’s Saturday and you have to get bread. It’s only a few minutes’ walk down your street, but you know that your town is a beehive of eyes and that you will chew your lips and your tongue and your cheeks if someone looks at you today and doesn’t see exactly the you who looked good enough in the frame of the mirror, good enough for dad not to have stopped you before you reached the door, good enough for the prettiest girl in the class to say you’re cool. No matter if it’s just an outing for a loaf of bread. You’ve done the shopping and now you’re walking proudly with a warm bag in your hand, the pavements are deserted, the sun is so strong you’re convinced it will reveal the last hints of red color-shampoo in your hair. The street is empty and you feel you can be anything you want. You wonder whether that’s the way real women feel, tall women, women with breasts, when they go to buy bread. And then you feel a heavy arm round your shoulders and another hand on your elbow. You don’t know them, but they must come from round here, they stink of sweat and alcohol. Their closeness is like your cutoff nail, almost painful, the blood is right here, at the edge. At first you don’t understand why they’re so close to you, but then they start talking, panting into your ear and then you get it. You’re all walking along your street which is suddenly emptier than it was, although a moment ago you were the only person in it, and now there are three of you. Sharp hairs scratch your face. They say you’ve got a nice bum, the one you’d seen earlier in the mirror, in the awesome flacks, no, in the slacks, the bum of a little 14-year-old girl who’s conscious of her bush. But now you’d like to set fire to all the bushes in yourself and fold up like a box into one simple flatness. You want to be reduced to two dimensions just so that these words in your ears disappear and this chin against your cheek and this hand on your elbow and this stench that scours your nostrils. Your street is even emptier, the houses are like boxes, like you too, behind their windows there are no more eyes, the mothers are in their kitchens, the fathers are watching the news. You must do this on your own. He keeps on talking. Now he’s telling you what he’d do to you, what he and his mate would do to you, and you don’t want to cry, because then you’d be a small girl again who can’t say slacks and then everything that’s happening would be even harder. You have to put up with this, like that boiling water that kills the red in your hair, you have to hold out until you get to the door that’s almost here, quite close. You have to stop: in your feet, your legs, your stomach, your elbows, your lungs, your hair; you have to stop completely. And you’ve succeeded, now you’re just a reflection walking along the street, that body from the mirror, but without you in it. A body that’s seen, touched, discussed, cursed, mocked, caught. A body that’s walking in those slacks, in that sweatshirt, a body that’s bearing his heavy hand on its shoulders. The body is reaching the door and unlocking it while those two guys go on their way with a few last remarks: about the lips of that body and the throat of that body and what all they would shove into that body. The body carries a bag with warm bread in it, the body hurts because today blood is gushing out of it, the body climbs the stairs and begins to shake in its two dimensions like a crumpled banknote in the wind. The body enters its father’s house and now it’s wild, bloody, sweaty, crying, and its father takes it in his arms and asks what happened. The body doesn’t tell its father exactly what happened because all that happened were words which the body doesn’t want to repeat, because the body is ashamed of itself in those words. The body feels that the body is to blame, it came out of the frame of the mirror and went into the street to buy bread wearing awesome slacks. It should have stayed inside, without legs or one shoulder. But the father holds the body, the father loves it and protects it. Protects it from the street, protects it from bushes. The father strokes its hair and says softly: Who’s my girl? My little girl. And the body shrinks until it’s small enough to fit into its father’s hands and its father’s question. The bushes wilt within the body and blood returns to the damaged tissue and its nails are once again as soft as a newborn’s. The body subsides in its father’s embrace while its mother slices the warm bread in the kitchen. Because today’s Saturday and it’s time for lunch.

__________________________________________________________

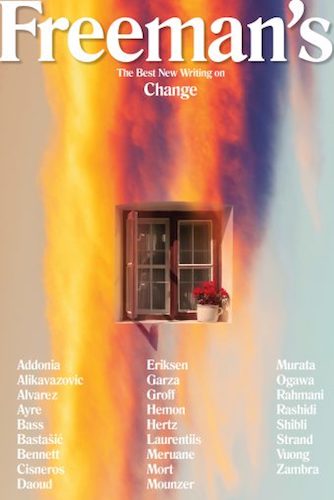

This piece is from The Freeman’s issue on change, published by Grove Atlantic.