Brandon Taylor: When to Protect Your Characters, and When to Punish Them

On Alice Munro, Karl-Ove Knausgaard, and the Impulses of the MFA

The first time I workshopped a story at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop was a wholly violent experience, the aftershocks of which still pulse through my life. I had heard rumors both about the teacher and about the place in general. Before I came to the Writers’ Workshop, I was living in Wisconsin, studying science. A friend of mine there was a graduate of the workshop from ten years back, and each time we ran into each other at parties, she’d lean back and laugh and tell me what a great time she’d had, and then she’d begin to unspool for me the same five or six negative incidents that had plagued her time here. I put up a story for workshop knowing that this was the sort of place whose students, even almost a decade later, carried with them bruises of having their work split apart. So when I say that my first experience of being workshopped at Iowa was violent, I don’t mean to imply that it was also surprising. The violence, I came to understand, was more or less the point.

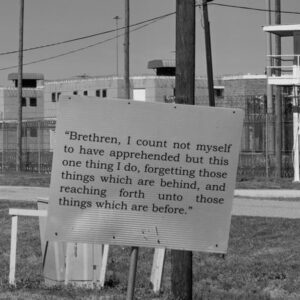

Another thing about that first workshop was that I heard something about myself that I had never heard before: that my story was protective and civilized and carefully managed. These to me seemed the primary virtues of fiction that I loved and that I wanted to write. There’s nothing I want more than peace and order. I had a difficult life. A strange life. And so in turning to fiction, I wanted to create for my characters a space where the urgent material of their lives would not contain the question of whether or not they would live or die. I wanted to write about people moving through the world who could count on more time, who didn’t have to confront the ugliness of violence and harm and malevolence. I wanted only to make for my characters a space where they could be. I left the workshop that night feeling like I had been struck by lightning. I was angry and ashamed.

The thing I have been thinking about for the last year—every moment of every day almost, and certainly every time I sit down to write, or think about writing—is this question of protectiveness, of orderliness. These traits were presented to me in the way a doctor describes some malformation of the inner ear or bad nerve in the lower spine: not a catastrophe, but not quite as it should be, either. Like I’d have to spend the rest of my life compensating in ways minor and major, making myself slightly more brutal, slightly crueler.

It makes sense that the stories I wrote entirely by instinct would contain in some greater concentration all of my natural faults and predilections.

When you know where to look for it, protectiveness is easy to find. Instead of letting the character say the one thing that cannot be responded to, let them say something else, something quippy or funny. Instead of having the character bash someone’s head in with a rock, an act that may be justified but is difficult to redeem, have them slap someone or say a mean remark, or, better yet, circumvent the violence altogether and let them brood silently. Why force characters who disagree to interact when you can isolate into separate silos of civility, everything suppressed, everything submerged, nothing bestial threatening the order.

Without understanding that it was happening, I had become a master of cushioning the blows of life for my characters. I scooped them out of awkward situations. I placed them gently into tense but not too tense relationships. I gave myself lots of room, lots of air. Many of my stories before I came to Iowa were suffused with a tonal density. I thought that by working in the subliminal currents of life, I was avoiding all that mess as I saw it. I didn’t know how to write myself out of things, and so I wrote around them. It helped that I was interested in the banality of daily life. However, when I began to notice it, I felt even more ashamed. I felt like everyone could see it in my work. I felt like they knew something wasn’t right about me, that I lacked an understanding crucial to the practice of writing. There were days when I couldn’t bear to even go to Dey House because it felt like everyone knew I’d failed, like they knew my work was hollow and that my control was really a desperate stratagem of fear.

It makes sense that the stories I wrote entirely by instinct would contain in some greater concentration all of my natural faults and predilections. I could feel myself searching out these faults story by story as I made my way through first year. An overdependence on tone. A lack of specificity with regard to place. A weak sense of point-of-view. A lack of narrative scope. A tendency to write stories in long, unbroken scenes. An opacity, as one of my teachers said. An aversion to interiority. An unwillingness to explain. But chief among these was protectiveness. No matter what I did, no matter how I sought it out to eliminate in my work, it recurred like something chronic. In my early drafts, there they were, all of the dodged conversations, the evaded confrontations, the tasks to which my characters invariably rose. And the feedback I received was always the same. Here I had written a quite lovely story that had properly proportioned scene and summary and backstory and present narration and tension and dialogue. It was paced well. But at the center of each story was a critical failure to ignite. Because I had so isolated my characters from each other.

I thought it was true that my stories needed, not greater stakes exactly, but a greater sense of urgency.

I tried many things. I tried subjecting them to more violence, but this made me queasy. I tried cutting them open and letting all of their thoughts and feelings rush out and mingle with narration, with exposition, so that I achieved the much-vaunted interiority, but this annoyed me and felt heavy-handed. I tried a thicker narratorial style, so that voice of the narrator would intrude and cast judgements that I did not feel I could ascribe to my characters entirely, but this felt too postmodern and trite.

I thought it was true that my stories needed, not greater stakes exactly (because I was writing about the greatest of stakes already: love, belonging, family, memory, loss), but a greater sense of urgency. Situation. I could get characters into scenes, and I could get them talking to each other, and I could have them do things. I could get them right up against each other, but in the moment when something irrevocable needed to happen, I faltered. I stepped away. I built in a secondary escape hatch. My stories became less stories and more a magician’s box. A trick. I had achieved a level of competency that allowed me to see the nature of the problem in my work, but I did not know how to fix it. And I did not know to whom I could turn.

*

For some time now, I have been reading the work of Norwegian literary superstar Karl Ove Knausgaard. His six-novel cycle My Struggle is so well documented in the literary and critical press that it’s almost silly to attempt to describe it here. There is also the great difficulty of trying to describe the art itself, which is certainly a part of his project. I think the phrase I encounter most often when reading about My Struggle is unliterary. Reviewers and critics alike are struck by what they consider a very unwriterly style and a focus on the mundane facets of life. They describe it as a literature of nothing with a tittering, almost gleeful embarrassment.

Through the layers of this useless abstraction (after all, what can be more literary than an unliterary novel about the mundane nature of life), it is possible to glimpse a contraction in what is deemed a worthy subject of literature. Knausgaard’s style is described as being plain and direct. Unadorned. There is an almost urgent desire on the part of critics to let us know that this writing is an act of un-writing. I suppose this must in part stem from the fact that Knausgaard has stated that he began the project of My Struggle in an attempt to get outside of the traditional idea of a novel as fiction. He has said that the only way he could write was to write the truth, all of it, as he remembered. And so he set out in this diaristic way. A remarkable feat for a man of self-admitted pathological vanity and shame.

I think what we come to understand of others is a kind of deep oceanic static, the hum of our cosmic isolation from one another.

There is a kind of anti-protectiveness at the center of Knausgaard’s project. The characters in the My Struggle novels are not fictional. They are people from his life. Or, perhaps a different way of putting it is that they are as real as any version of another person can be to us. We are always selecting and curating. We are always inventing other people, even though they might only be sitting across from us at a table or on a bus or in our beds. Other people are unknowable. The facts of their inner selves remain as deeply mysterious as the bottoms of the oceans.

There is an idea that you come to understand people after a while, after you have known them for long enough or when you share some mutual connection. But I think what we come to understand of others is a kind of deep oceanic static, the hum of our cosmic isolation from one another. But still, when you affix a real person’s name to a character in your novel, a connection is being made. Or an argument of a connection is being made. And when you put their dialogue in quotation marks, as Knausgaard does, there’s a kind of magic trick at work. You are saying, in some sense, that this is how it was. This is what you said.

The problem here is obvious. By calling it a novel and not a memoir, Knausgaard tries to side-step the sticky business of writing his true thoughts about the people of his family, the people of his life, and he is setting down for all the world to see all of the things that he might have otherwise wished to remain a secret. In my experience, people are never prepared to hear about themselves from you. But for six books, Knausgaard goes on about even the most damning materials of his life.

Toward the end of the first book, Knausgaard writes about his grandmother’s house, where his father has been found dead after years of heavy alcohol abuse. It is a wildly uncomfortable section, and it is easy to imagine to how Knausgaard might have been motivated to write differently, protectively, shielding his now-dead father from judgement. Trying to soften details. But instead, we get a meticulous accounting of the squalor of his father’s last days:

In front of the three-piece suite by the wall lay some articles of clothing. I could see two pairs of trousers and a jacket, some underpants and socks. The smell was awful. There were also overturned bottles, tobacco pouches, dry bread rolls, and other rubbish. I slouched past. There was excrement on the sofa, smeared and in lumps. I bent over the clothes. They were also covered with excrement. The varnish on the floor had been eaten away, leaving large, irregular stains.

By urine?

Of his grandmother, who had been living in the house with Knausgaard’s father as he drank himself to death, Knausgaard offers this depiction:

The dress she was wearing was discolored with stains and hung off her scrawny body. The top part of her bosom the dress was supposed to cover revealed ribs shining through her skin. Her shoulder blades and hips stuck out. Her arms were no more than skin and bone. Blood vessels ran across the backs of her hands like thin, dark blue cables.

She stank of urine.

I have gone back and forth about whether or not the above descriptions are exploitative, and if they are, of whom. Those who are less generous in their view of Knausgaard’s project (and the people depicted within the novels themselves, his relatives) have charged him with using private pain for public recognition, or for selfish means. Knausgaard’s uncle, Gunnar, who figures prominently in this section, did not respond favorably to Knausgaard’s depiction of the events within the novel. There were threats of a lawsuit. This all plays out in the sixth and final My Struggle volume. One wonders, then, if the above passages, with their focus on the physical details of a life in decay, are doing something that is in fact an element of genuine literature. Or is Knausgaard simply reveling in the detritus?

Radical openness, a willingness to let the story do what it must in order to be truthful, is certainly important to the project of trying to be less protective of my characters

His relationship to his father was complex (it is the subject of the book and perhaps the entire novel cycle). To Knausgaard, his father was a tyrant and a bully and a man in deep, existential pain which was difficult if not impossible for a child to parse but which comes into view later, as the cycle progresses and Knausgaard himself comes to understand the difficulty of life. But he also loved his father, as the novel goes to great lengths to show.

The first time he sees his father’s dead body, he cries, an act for which his father always chastised him. In the fourth novel, about his adolescence and early adulthood, Knausgaard writes of going to stay with his father briefly over the summer before he has to report for teaching duty in the north of Norway. His father and his new girlfriend have a condo, and it appears that at long last these two have entered a detente.

But the signs of decline are already in place. Knausgaard describes this newly mellowed version of his father with confused curiosity. His father’s new propensity for floral shirts and late-night dance parties are unlike the strict, harsh teacher he had been before divorcing Knausgaard’s mother. Knausgaard doesn’t know what to make of this person who is his father and is not his father. He doesn’t know what to do with his father’s kindness, or lack of care. Knausgaard arrives at the conclusion that his father is actually just deeply ambivalent and that the change is motivated by some sort of mid-life crack-up.

As a strategy against protectiveness, this seems a good one. A commitment to the thorough and meticulous documentation of a person’s wavering, their ambivalences, their faults, their follies, their late-night parties. The drinking when it begins is at first funny, an amusing change in the man. It isn’t freighted with meaning. It isn’t depicted as an act of violence. Not when the father is already so emotionally violent to Knausgaard. But even this violence is treated as a natural extension of his love. It’s just that his love makes Knausgaard cry. It makes Knausgaard’s brother frustrated. This is a family on the verge of catastrophe. Tension runs through every scene in which they appear together and separately. These personal geometries are acute.

But it is Knausgaard’s dedication to detail that lifts the work above mere sentimentality or vendetta. I think what I admire most in the My Struggle books is Knausgaard’s willingness to be vulnerable, to an almost radical degree, in the form of autofiction. Vulnerability, the willingness to be seen and to be judged, drives these novels. In the second of the My Struggle novels, Knausgaard writes of the first time he met the writer Linda Bostrom, who would become his second wife, at an artist’s colony. Following her reading, he flirted with her and tried to get her to sleep with him, but when she rejected him, he went home drunk and cut his face with broken glass while looking at himself in the mirror. The self-mutilation goes on over the course of several pages. It is described in painstaking detail. Every cut, every sensation, every drop of blood. He knew certainly that she would read this book. That his first wife would read this book and would discover the extent to which he had been unfaithful to her. And yet it is all there. All of it, the roiling human mess of it.

It is not merely that he wrote these deeply personal and autobiographical books. It’s that he did it knowing that he would be making people privy to his version of their lives. And he did it anyway. It’s remarkable. And perhaps more than a little selfish, that is true as well. But radical openness, a willingness to let the story do what it must in order to be truthful, is certainly important to the project of trying to be less protective of my characters. To let their lives play out how they must. To play it as it lays.

Radical vulnerability is one way to confront of the question of protectiveness in fiction. Another method is the brutal compassion displayed by Alice Munro. In her collection Too Much Happiness, the stories are filled with catastrophes and horrible acts. In her excellent story, “Dimension,” Munro writes with an easy fluidity about a woman whose life has been utterly destroyed by her husband. He murdered their children in a rage when she refused to come home because she feared for her safety. It’s a story all about the limits of personal determination and how we can live in the world after the worst possible thing has happened.

Where some writers might have gone up to the point of the murders and stopped (and I count myself among this number), Munro does that thing which makes great writers great, she goes beyond into the after and crafts with the same easy patience the remnants of Doree’s life. And then things get stranger still as Doree begins to visit her estranged husband in the mental hospital where he has been incarcerated since the murders. She’s living a small, anonymous life now. And she’s tried to kill herself twice. And still she visits him in the hospital. When he makes a revelation that he can hear their children talking to him, she is at first startled and then something like relief overtakes her.

I find this story fascinating because it is the kind of story I would find impossible to write. I am so afraid of what comes after catastrophe. Or, in my experience, what comes after catastrophe looks so much like what came before catastrophe that it feels narratively uninteresting. My imagination is wired, it seems, to keep catastrophe at bay. But Munro does not protect her characters. She flings them out into the universe. Or she calls the universe to them, and the results are striking. The story shapeshifts mid-way through and it becomes not a story about a woman to whom horrible things have happened necessarily, but a story about how a person gets on with life. Or how they can’t get on with life. It’s a story about all the ways that our personal geometries align and mis-align in our conceptions of ourselves. Munro utilizes a similar technique to Knausgaard. The matter-of-factness of the disasters:

It was a cold morning in early spring, snow still on the ground, but there was Lloyd sitting on the steps without a jacket on.

“Good morning,” he said, in a loud, sarcastically polite voice. And she said good morning, in a voice that pretended not to notice his.

He did not move aside to let her up the steps.

“You can’t go in there,” he said.

She decided to take this lightly.

“Not even if I say please? Please.”

He looked at her but did not answer. He smiled with his lips held together.

“Lloyd?” she said. “Lloyd?”

“You better not go in.”

“I didn’t tell her anything, Lloyd. I’m sorry I walked out. I just needed a breathing space, I guess.”

“Better not go in.”

“What’s the matter with you? Where are the kids?”

He shook his head, as he did when she said something he didn’t like to hear. Something mildly rude, like “holy shit.”

“Lloyd. Where are the kids?”

He shifted just a little, so that she could pass if she liked.

Dimitri still in his crib, lying sideways. Barbara Ann on the floor beside her bed, as if she’d got out or been pulled out. Sasha by the kitchen door—he had tried to get away. He was the only one with bruises on his throat. The pillow had done for the others.

Some people might call this clinical or cold. They might describe the writing as staccato (a nonsense word) or detached or some other gibberish word like dissociated. But I don’t think it is. What Munro has rendered here, I think, is what it feels like to be jammed so far down inside of yourself that you barely have space for two thoughts and so everything gets elongated, dilated. It’s not a lack of time between moments. It’s too much time between moments. The unreality of life. It is also striking to note how much like previous exchanges between Doree and Lloyd this is. There isn’t some false heightening of rhetoric or a lapse into lyricism. There isn’t a distinct tonal shift. What is so terrifying about this moment is how ordinary it is. How self-same with the rest of their lives this is. Terrifying because the inertia of life will carry them forward into more self-same days and also horrifying because this could have happened at any other time. Doree of course does not have the sense of having escaped disaster, calamity. What she has is a sense that her world has been upended, destroyed. But later in the story, as she’s on the bus going to visit Lloyd in the facility, she has a revelation:

Who but Lloyd would remember the children’s names now, or the color of their eyes? Mrs. Sands, when she had to mention them, did not even call them children, but “your family,” putting them in one clump together.

Here she is thinking about the nature of families and of memory and of loss, and here she is ceding to Lloyd some bit of grace. I would have been tempted to write this line more angrily. More wrenchingly sad. I would have set it aside with tone. I would have embellished. I would have grown lyrical, perhaps. I would have used abstraction. I would have been squeezed to the margins of the story by this feeling, this vast, incomprehensible feeling. But Munro writes—in the rhythm of life as though she were describing polishing a mirror—of how a person could realistically come to miss someone capable of such gross violence.

I am not naïve. I am not stupid. Trauma is complex. Human relationships and histories are complex. We never feel one thing at one time. But writing is sequential. There is an order. I struggle with how to convey the simultaneity of things, the necessary same-time-ness that gets you such gutting revelations.

It’s not a lack of time between moments. It’s too much time between moments. The unreality of life.

Could I have even written a Lloyd? I think I would have failed on several scores. I think my great fault in writing is that I am always trying to couch action in easily discernible motivations because if the motivations are understandable, then the action can also be understood, and if the action can be understood, then it is not so bad. It’s an artifact of workshops, I think. Writing stories to be understood so that the discussion goes smoothly. I am at core a people pleaser because I was raised by brutal people who could not be pleased. It is a strategy.

But Munro writes with the kind of open, clear ambiguity that is so much a part of reality and life. Munro demonstrates that compassion and protectiveness are not the same thing. She does not deprive her characters of whatever strategies they have devised to soothe and comfort themselves. They aren’t furious little trains on plastic tracks or fixed routes. The audacious strokes of Munro’s work are in the subtle maneuvers she depicts as her characters search out their footing, trying to find their way. Her characters feel singular because their positions are hard-won, the result of a lifetime.

Munro can write a murderer and make it seem plausible. I hate this word plausible. Because the world is full of murder. It is full of horrible things and horrible people, and yet this idea of even-handedness has permeated our literary culture to a degree that verges on pathology. Characters are expected to be bad but also good. We are expected to write every character to the full width and breadth of humanity, but humanity in fiction is actually a misnomer, I think. What people call humanity is really just relatability. We think that villains who pet kittens are complex. We create for people who do bad things elaborate back stories in order to make their evil plausible and human because true evil is rare. And so we end up writing minor villains and petty evils.

*

I worry sometimes that I will always be protective of my characters. That I won’t have the tools to intervene on their behalf, that I’ll always only half-write them because to fully write them would be to subject them to the vagaries and the ambivalence of the universe. It’s not because I write autobiographically. Indeed, my inability to write autobiographically is an extension of my protectiveness. It feels cheap to write about trauma when I have experienced trauma. It feels too readily available. And also, it is difficult work. It is hard to write about people you know, who exist. I always thought it was harder and therefore more worthy to write about things that had not happened to me. I always thought that to be an artist, one had to use one’s experience indirectly, otherwise it was simply tawdry and tacky.

This of course is silly. It is also perhaps the result of being a black person in America. It is not a new idea that the work of black writers is treated as merely sociological, that its value is a direct result of its capacity to teach white people about black pain. The same is true of queer narratives, that our stories must be oriented and evaluated via the rubric of the surveilling culture. In this way, my work is a kind of minor literature. And so I chose to write about other things.

I also couldn’t write about my own pain and my own family and my own self because I didn’t trust myself not to write a screed. Fiction, the complexity of people, the difficulty of writing about those who have harmed you in some way. So I swore it off. I felt a great sense of shame anytime someone read my work as autobiographical, not only because this was untrue but because I felt as though I were being reduced in some way. Either because my work was not good enough or my life was too bad to make the basis of good art.

I am protective of my characters, I think, also in part because no one was protective of me

I am protective of my characters, I think, also in part because no one was protective of me. I try also to make art for people who want a refuge from the inescapable reality of life. I didn’t want my characters to suffer because there has always been such a premium on my suffering. On the suffering of black and brown and queer people and poor people. I didn’t want that. I also didn’t want to contribute to a cheapening of the narratives of black people from the South. I didn’t want to write more cornbread stories about beleaguered grandmothers who sang gospel while they cleaned. I rejected my life. I rejected my stories. I rejected the idea that I had stories. Because how cliché, how boring to become what other people expect you to become.

It seemed important to me that I write from this place of rejection. That I write from a place of pure aesthetic concern. That my characters be free to do what they wanted.

But I had actually reduced their degrees of freedom considerably. I had hollowed them out. I prevented them from engaging. From being in the world. Munro’s capacity to get her characters into trouble without a clear idea of how to get them out—or even caring if they do—is brutal, yes, but her characters are so fully themselves that it never feels like she’s punishing them. Knausgaard’s interior states are laid out with such care and detail that he too is fully rendered. The shame and the beauty go hand-in-hand.

I have been a benevolent dictator. I have ruled over a tiny cosmos of people sealed in perfect bubbles. In thinking about Munro and Knausgaard, I think the idea is that one must be willing to leap and to plunge and not expect to rise, but to find in that great descent if not meaning then at least peace, or joy in the motion. The hardest thing in the world is to begin writing with no clear idea of how you’ll get yourself out. It’s hard to commit to mystery. It’s hard not to expect to rise. It’s hard to let people do what they must, even if that means turning away from us.

When someone raises a fist, we move to protect ourselves. It is an ancient geometry: assault and recoil. But the vertex, the point on which it all swings is personal. The locus is the self. The objective is the self. I must write better, I think. I must write characters who get themselves into things and I must let them. I must let them tear themselves apart trying to do the thing they need most to do to stay alive.

It is difficult.

Brandon Taylor

Brandon Taylor is the author of the novel Real Life, which was a New York Times Editors’ Choice. His work has appeared in Guernica, American Short Fiction, Gulf Coast, Buzzfeed Reader, O: The Oprah Magazine, Gay Mag, The New Yorker online, The Literary Review, and elsewhere. He is a staff writer at Lit Hub. He holds graduate degrees from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where he was an Iowa Arts Fellow.