It is a strange thing to be a family of the missing. Deaths are commonplace. But a disappearance—it has the scent of murder in it, and there was little we could do to absolve ourselves. After Lee went, we continued our chores, but the work seemed dull without the promise of something new arriving to us. We canned our meats for the cellar, patched our woolens. We readied enough wood for the cold. There were repairs to be made and weeding to finish, plants going to seed and in need of pulling, the fields mulched with hay and manure. We had frosts by the end of October, a hard freeze that left a cake of ice on the sheep’s drinking water. Our brood cow gave birth to a starveling, and Ray believed she wouldn’t last the month. The summer crops were gone after that, save what we had already stored. With so few hands, Ray worked fourteen hours a day. Agnes grimaced at the layers of manure on her boots, and Patricia’s knuckles swelled. “I do hope that boy can find them,” she whispered in the kitchen. “I most certainly do.” Already a month the girls had been gone. NO SIGN, Lee wrote in a telegram. STILL LOOKING. He never sent an address. At night with my eyes closing, I went through the books with a pencil, tallying our earnings and costs—three fewer stomachs, six fewer hands. I marked the difference at the bottom of the page with a shaky line. Hope, it was a terrible expense. We couldn’t let anything go to waste. And we couldn’t risk the extra we might set aside only to spoil if Lee and the girls didn’t return soon, if the girls didn’t return at all—though I couldn’t let myself think it. Mother had said the same near the end. None for me, she’d said when I brought a plate to her bed. This war. You’re all thin as bones.

This is not a place where people easily vanish. It is good clean earth for miles, straight as a table, our acres bordered by the river on one end and a rat of fenceline on the others, the distance between a long walk of cropland that takes more than a day’s plowing. There is a low feeling to living here, the horizon far and wide with hardly a soul to break it, yet if you kick in your heel and wrench up a clot of dirt, how many thousands of creatures burrow through the earth beneath. In every direction our neighbors’ acres are the same—more than a mile of farmland between us and the Clarks to the west, the Elliots to the south. In winters we don’t lay eye on either family for weeks. The river between our acres and the Elliots’ swallows its banks, higher from one season to the next. Bottomland, they call it, but the water could very well drown us. Father said we should be thankful to have so much. “There’s nothing more honest than this,” he said. But I think honesty is different from emptiness.

NOTHING, Lee wrote in a second telegram. NOT YET. One night in November, hours after I had gone to bed, I had a dream. Myrle walked across the yard in the dark with the door to the house open behind her, and I saw myself standing just inside, watching. She was drenched to the skin. Her nightgown was sheer and stuck to her, her hair running with water. With the distance between us, I could not see her face. Instead of calling to her, I closed the door and locked it fast with my key. Outside the window, I could see her. She was running back to the house, to me.

I woke. The sound of knocking. When I sat up, the sound was gone. I took my lantern out into the hall and checked the door, the window. Both were closed, locked. Outside, only darkness. I carried my lantern up the stairs. The door at the top was open, the room now empty. On the girls’ dresser, Myrle’s dove-colored comb was gone, but the cutout of the woman’s hand remained. Esther’s pillows stood against the headboard but the wrong way, her bedspread crushed, nearly pulled off. The broken chair had been taken, as if to banish any thought of it. Only Agnes’ drawings were the same—Mother with her pale hair, her eyes gray. If the girl had the chance, in forty years Myrle would be our mother’s twin.

I opened the window to catch my breath. The ground below was dark as pitch. The gash beneath the sill felt sharp with slivers, as if something had bitten it. I thought of the hammer I had kept for myself, bundled in the linens of my room. It had a blunt rounded nose, its ears worn from pulling nails. The wooden handle curved just under my thumb, as if it had been mine all along. That gash, as wide as three fingers. The width of the hammer was the same, as if the hammer had broken the sill, pinned to hold something. Still, the gash itself seemed deeper than any my sisters might have left. From where I stood, the fields were gray with ruts of soil. Farther out, the trees were bare and black. Then nothing. Somehow, for some reason, the girls had gone running into that nothingness for all their worth.

They would have needed a rope. It might have been the dark of the room at my back that told me, or the way my lantern lit the side of the house. If only one of my sisters had used the key and the other had blocked the door with the chair and gone through the window, they’d have needed a rope for the second girl to climb out—and it would have been Myrle. Close to hysterical at the drop and the only one slight enough, but Agnes was right. Esther could convince anyone to do such a thing, and Myrle more than that. Myrle, so sick those many weeks then suddenly not, and Esther with all her prowling—enough to make a plan. But what had made them want to go?

I walked out. The ropes we kept in the shed, the shed closer to the barn than the house and facing the fields. Around the foot of the shed, the mud was trampled, and the lock on the door hung loose, broken, the door gaping. It was an iron lock Father had made, as large as my hand and heavy. When I let it go, it snapped against the door. This farm never left things to ruin, not like that. I opened the door, but both our ropes lay coiled together at the foot of the wheelbarrow, the wheelbarrow rusted from the weather and the ropes wet to the touch.

A shuffle in the dark. I stepped out. Someone stood at the riverbank in the distance. An old man, stumbling along with his cane. Since Mother’s illness, Father had often wandered. A dried-up dugout on our land had long been his favorite hiding place. Now he made slow going of it, stepping into the water as if half awake. In the low light, it lapped his knees, the thighs of his trousers. The water must have been cold enough to fill his boots with pins, the hour so late no man or woman would have wandered out unless driven. I thought to bring him back into the house, but he whipped at the water with his cane and whipped it again. I remembered my dream. How many times had Myrle come swimming here? But never in such darkness or as cold as it must have been. And never alone. I couldn’t make sense of it, her feet wet on the doormat. I wouldn’t let myself imagine what it might mean. I snuffed out my lantern and hurried blindly inside.

****

“I don’t know why he sends each of you here,” the deputy said.

I sat across the desk from him and drew my head back. I hadn’t seen the man since his business at our house, more than a month ago now, and I didn’t know who he thought was sending any of us. His office was a poor scrub of a room, the side door open onto the creek that ran through town. It could have been an outhouse, that creek, for how dimly it smelled. On his desk, a placard with the name SHEFFLY in gold. The deputy dropped his chin, turning a pencil between his thumbs. “I’ve told you we’ve found nothing,” he went on. “We will come to the house when we do.”

“I know, Mr. Sheffley, it’s just . . .”

The man groaned. “No, you do not know.”

He puffed out his cheeks and I thought about the gash beneath the window and the hammer in my bag.

“Look,” I said.

But he shook his head. “Miss Hess, this is a difficult time for all of us. Every other month, another farm goes to the bank, and there’s who knows what in those empty houses. And every morning my wife asks for milk for our newborn, though she knows very well we can’t afford enough. How can a father not have milk? We’ve got men on the roads, holing up behind every open door, and my wife sits in our house and weighs the child on the hour. When I get home, she never fails to tell me he hasn’t gained an ounce more.”

My face burned. What did he know of children, with only an infant? His worse complaint was that the child was thinner than he should have been? What if the boy disappeared altogether?

“You don’t understand,” I said. “If we stop coming . . .” But I couldn’t finish. I drew my shawl to my throat.

The deputy returned to his papers, twisting his neck as he worked. The bag was heavy on my thighs, my hand gripping the hammer inside. Didn’t its presence in their room, so strange in itself, prove something was wrong? That these girls, runaways or not, were different from the men in those sorry houses? And different needed attention. It must have had some terrible cause. I imagined the deputy turning the hammer over, an object strange to him—for surely he had rarely held a nail. He had never milked a cow or raised the wall of a barn. I imagined him dropping it in his drawer to be used for a later time, and Ray missing it, or even Lee. What good would giving the hammer to such a man do any of us?

I sat up straight and closed my bag. “If we stop coming here,” I went on. The deputy didn’t raise his head. “If we stop coming,” I repeated, louder. “It would be like the girls have stopped. Like everything has. It would feel as if we had only just imagined them.” My voice broke. “Why, my own brother has gone off to look for them. And he’s not well. Ever since the war, he gets so easily confused.”

“He seemed a perfectly capable young man.” The deputy opened a drawer and drew out a pile of posters. “Beautiful faces,” he said without a glance. “Someone in your house must have spent a great deal of time, but I don’t know what good they’ll do me. Those girls ran off. I’m sorry to repeat myself, Miss Hess, but you must listen. Everyone in town knows. Your brother, however confused, obviously does too. Girls, these days, they are so much older than they used to be. It’s not my job to post advertisements, necessary or not.”

“But these aren’t . . .” I snatched the posters from him, a dozen of them or more, surely brought here by my own sister. The girls weren’t so old as that. Not so old they might have done the very thing I had been thinking of for years.

“All right,” Sheffley whispered. His pencil rolled down the slope of his desk and came to a stop near the edge. His eyes took on a dazed look, as if something had gone missing. He bent his head to his papers again, but his hand was empty, and he searched nervously about.

“Babies,” I mumbled. I stood from the chair and left him looking, though the pencil lay neatly on the edge of his desk, as close as my own wrist. Puzzled by an ounce of milk and not a wink of sleep. If the man could not find a pencil, how could he find anything else?

****

It was more than cold now. The wind rose, ice glazing the roads. We expected snow. With the hammer in my bag, I stopped at the market to buy a dozen nails—though it seemed a waste with so many at home—and found a tree that faced the grocers. Everyone knows, Sheffley had said, but surely not the strangers that passed through town. Biting a nail between my teeth, I rolled out a poster and held it straight. missing, it read, the girls’ faces copied by my sister’s hand. “Nan, you want to know a secret?” I’d heard Esther say once. The hair on my neck had risen, as if her voice might know something worth whispering about. But with a laugh she was gone, and her whisper gone with it.

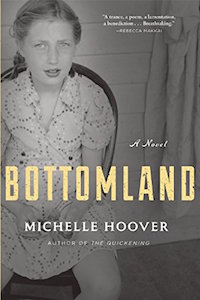

From BOTTOMLAND. Used with permission of Black Cat, Grove Press. Copyright © 2016 by Michelle Hoover.