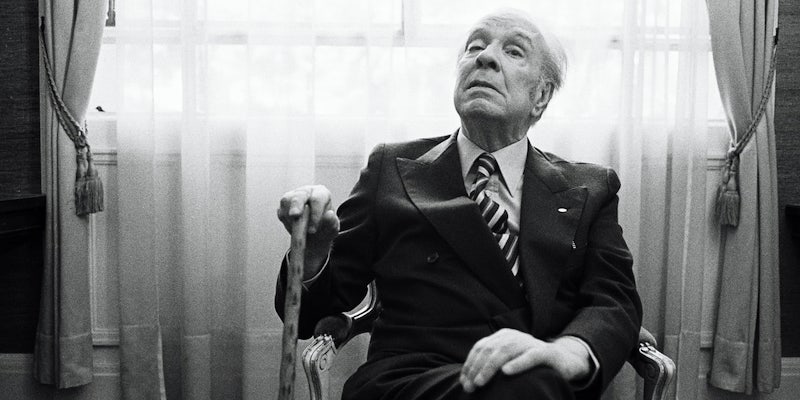

Borges Dealt With His Anxiety About Going Blind by Learning a New Language

Andrew Leland on His Own Weakening Vision, Braille, and Making a Commitment to Read with Visual Aids

The Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges lost his vision—what he called his “reader’s and writer’s sight”—around the same time that he became the director of the National Library of Argentina. This put him in charge of nearly a million books, he observed, at the very moment he could no longer read them.

Borges, who went blind after a long decline in vision when he was fifty-five, never learned braille. Instead, like Milton, he memorized long passages of literature (his own, and those of the writers he loved), and had companions who read to him and to whom he dictated his writing.

Much of this work—he published nearly forty books after he went blind—was done by his elderly mother, Leonor, with whom he lived until her death at ninety-nine, and who had done the same work for Borges’s father, Jorge Guillermo Borges, a writer who also went blind in middle age. (Borges’s blindness was hereditary, and his father and grandmother “both died blind,” Borges said—”blind, laughing, and brave, as I also hope to die.”)

Borges kept his job as director of the National Library, and he became a professor of English at the University of Buenos Aires. But literature had become, for him, entirely oral.

Borges decided to use the occasion of his blindness to learn a new language, and his description of the pleasure of learning Old English reminds me of my first forays into learning to read tactilely:

What always happens, when one studies a language, happened. Each one of the words stood out as though it had been carved, as though it were a talisman. For that reason poems in a foreign language have a prestige they do not enjoy in their own language, for one hears, one sees, each one of the words individually. We think of the beauty, of the power, or simply of the strangeness of them.

In the newness of Old English, Borges found an almost tactile relief in the unfamiliar words, as though they were “carved,” like the raised print in those first books for the blind printed in Paris nearly two hundred years before. But because Borges never learned braille, his experience of literature remained fundamentally sonic: “I had replaced the visible world,” he said, “with the aural world of the Anglo-Saxon language.”

In the newness of Old English, Borges found an almost tactile relief in the unfamiliar words, as though they were “carved,” like the raised print in those first books for the blind printed in Paris nearly two hundred years before.In the same lecture, Borges listed the “advantages” that blindness had brought him, but they all strike me as banal, things he could have easily had as a sighted writer: “the gift of Anglo-Saxon, my limited knowledge of Icelandic, the joy of so many lines of poetry.” He is pleased to have a contract from an editor to write another book of poems, provided he can produce thirty new ones in a year, which he notes is challenging considering he’ll have to dictate them. This makes it sound like adapting to blindness for Borges meant, very simply, carrying on his work as a writer.

But in his poems and stories, Borges strikes a less sanguine tone about becoming blind. In “Poem of the Gifts,” Borges observes the coincidence that one of his predecessors in directing the National Library, Paul Groussac, was also blind. The poem, which begins with the irony of God’s granting him “books and blindness at one touch,” is written in a slippery voice that may be Borges’s, or Groussac’s.

“What can it matter, then, the name that names me,” he says, “given our curse is common and the same?” Borges cannot distinguish between himself and “that other dead one”:

Which of the two is setting down this poem—

a single sightless self, a plural I?

The transience of the writer’s identity was a long-standing theme for Borges, one he developed in the work published after his blindness. “So my life is a point-counterpoint,” he wrote in “Borges and I”:

a kind of fugue, and a falling away—and everything winds up being lost to me, and everything falls into oblivion, or into the hands of the other man.

I am not sure which of us it is that’s writing this page.

Written in the years following his blindness, Borges must have dictated both this story and “Poem of the Gifts,” and both texts express a kind of authorial identity crisis. I wonder how much of this anxiety grew out of the loss of control he felt once he was forced to dictate his work.

I’ve experienced a form of this anxiety myself, as I confront the loss of my visual relationship with language. Once I can’t rely on sight to write anymore, will I, like Borges, no longer be quite sure who is writing this page? When I first tried writing with a screen reader, turning off my monitor to see what it was like, I had a flash of this dissolution: I typed too fast for the screen reader to keep up, so I wrote into a void, the words audible in my mind, but without any confirmation that they were actually being recorded on the screen.

It was like writing in water, or calling out into the darkness. Even when I stopped, and the computer at last read the text back, my words sounded strange, echoed in an unfamiliar, mechanical voice.

But in between writing the first and second drafts of this book, my eyes have gotten weaker, and I now leave the screen reader on all the time. The anxiety of losing my own voice to the computer’s has given way to a relief that I don’t have to strain and stretch so much to see. I’m like a guy who could walk haltingly on his own if he had to, but it’s so much easier to just use the crutches.

I’m still getting used to certain quirks—my braille display doesn’t always show me paragraph breaks, and when I’m speed-listening to a book, the reader burns through the ends of chapters and on to the next without stopping.I find myself looking away from the screen more and more, resting my eyes as I listen back to a paragraph I’ve just written. If I suddenly lost all of my residual vision tomorrow, I know I’d be overwhelmed, and the grieving process I’ve begun would be painfully accelerated. But I also know I’d be able to finish my work.

I’m still getting used to certain quirks—my braille display doesn’t always show me paragraph breaks, and when I’m speed-listening to a book, the reader burns through the ends of chapters and on to the next without stopping. I have to rewind, slow down, and artificially re‑create the resonant pause that the blank space on the page naturally offers a sighted reader.

But while I’m losing print, I’m not losing literature itself, which exceeds the eyes. The other day, with my phone’s screen reader on, I was reading the newspaper at a pretty furious clip. I’d run across the obituary of Ben McFall, the legendary New York City bookseller who worked at the Strand for forty-three years.

The piece ended by describing McFall’s deep commitment to his work, even after the pandemic and his failing health had forced him into the Strand’s corporate office, away from the line of friends and fans who would wait next to his desk amid the stacks to get a personal recommendation, or just to talk books. The obituary ended,

Mr. McFall, who was so attached to his Strand name tag that he sometimes wore it around his apartment, chose to keep it on even though he no longer spoke to customers.

It read: “Benjamin. Ask me.”

I had the speech turned up so fast that these last two paragraphs—which didn’t even register as paragraphs, since the babbling screen reader ignored the line break—took only a few seconds to read. And yet I still felt tears burst out of my eyes at that final image, of McFall’s commitment: not just to the pleasure of solitary reading, but to the community of readers who sustained him to the very end. My response felt like a sign that however awkward it might feel to read this way, I still felt the power of that community; I’m still a reader.

______________________________

From The Country of the Blind by Andrew Leland. Reprinted by arrangement with Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2023, Andrew Leland.