Bookworm in a Chrysalis: How Language Acquisition Nourishes a Love of Literature

Natasha S. on Being a Multilingual Reader and Writer

The publishing party for my first book was held in the bookstore I used to work at. My book was piled on the table. People with flowers, people with cups of wine, people who didn’t understand Icelandic all filled the store. I felt like it was my birthday. Ten days earlier, I’d been awarded the Tómas Guðmundsson Literary prize, which is given annually to an unpublished collection of poetry. I was the first Icelandic immigrant to do so.

Nothing in the store had changed. Boxes of remainders stood stacked behind me while I read. Sale stickers written in black marker adorned the covers of my books. The Harry Potter poster I’d framed myself was still hanging in the same spot. I signed copies with a ballpoint pen branded with the store’s logo, asked people how to properly spell their names, just to be on the safe side.

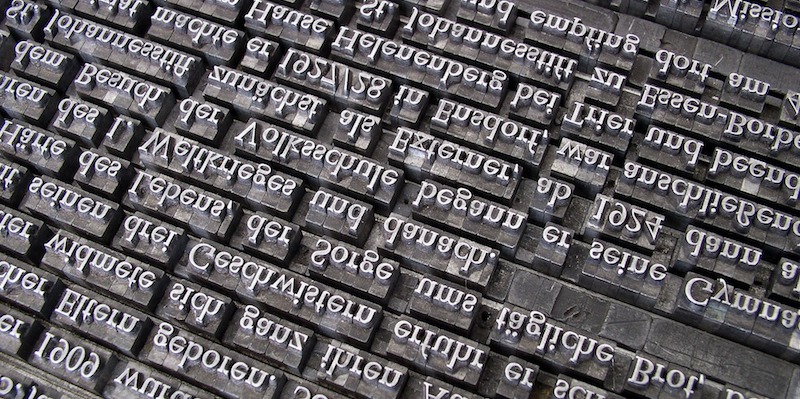

Bookstores are a crossroads, a place where publishers, authors, and readers come together. Books flow in and books flow out. We received shipments, distributed them among readers, returned those that didn’t sell. Every winter, during the Christmas book flood, we’d return hundreds of these remaindered books to make room in the store for new titles. I’d gather books from shelves and under tables, remove their price stickers, make a note, box them up, send an email.

Every winter, the shop filled with people in search of warmth while they waited for the bus, in search of Christmas gifts, in search of new stories. At first, book release parties added some sparkle to my work routine, then they became the routine. I filled out sale stickers with a black marker, organized the book table, poured wine into cups, put a pen on the table for signing. I stood between the readers and the writers, an invisible guest.

Tongues bring us together and divide us from one another.

Is a woman born a writer, or is that something she decides—dares herself to be? How and when does a reader turn into a writer? My transformation began in the bookstore, but my story started a long time before that.

*

Once upon a time, I got the idea that I’d read all the books on a list that the Norwegian Book Clubs and Norwegian Nobel Institute put together and called “The Top 100 Works in World Literature.” I’ve always enjoyed a challenge. I was living in Stockholm, was no longer a student, and could finally read for fun. I didn’t have a lot of friends and so I read a lot, before and after work. The timing for me to reconnect with literature couldn’t have been better.

The list was comprised of well-known classics, from The Epic of Gilgamesh to Blindness by José Saramago. A hundred authors from fifty-four countries were polled for the selection.

I often went for walks in the forest with my camera and an audiobook. Green trees, red and yellow trees, white trees. These promenades are what I miss most about my life in Stockholm. That’s where I got to know Henrik Ibsen, Doris Lessing, Alfred Döblin, James Joyce. I listened to the books in the languages I possessed—Russian, English, Icelandic, and Swedish—and I’ll always remember the voices of the actors who read them. I found some good stuff on the list, but often got bored when I read old books—they’d fallen out of context, and I couldn’t discern their literary value.

I’d been living in Stockholm for two years—as long as I’d lived in Reykjavík before that. I wanted to celebrate this milestone, so I decided to change tack and embark on a Nordic reading challenge instead. I spoke Icelandic and Swedish, I’d taken a summer course in Faroese once, and two short courses on Norwegian. The one Nordic language I’d never studied was Danish, but as far as I could tell from having read the back of an air freshener, it wouldn’t be too difficult for me to understand.

I read in all the languages I speak, and I try to keep up with the literature in those countries—Russia, Sweden, and Iceland. For a breath of fresh air, I read Japanese and French lit. Reading is an integral part of acquiring a language, as a tongue is an integral part of human anatomy. Literature is one of the forms that a language takes on. I’ve always been fascinated by it. It’s a tool for hypnosis. Words crawl into your ears and tidy up disordered thoughts. Value-laden language, which is used in propaganda, distorts feelings, opinions, and realities. Tongues bring us together and divide us from one another. Our language says a lot about us, it’s interesting to listen to it.

I began my Nordic challenge by reading Hunger by Knut Hamsun, one of the Norwegian books on the “100 Best” list, in Norwegian. I had to look up certain words, but the reading went well. Inspired, I continued onto Danish. Ole Lukøje by Hans Christian Andersen, which was also on the list, was up next. The story was short, the plot was familiar. The language was old—all the nouns were written with capital letters, like in German. Danish was a lot harder for me than Norwegian. Reading in Faroese felt somehow “old timey,” and I didn’t have access to any Faroese dictionaries. So, when I didn’t understand a word, I looked it up in an Icelandic or Swedish dictionary and one of those translations usually sufficed.

By the end of the year, I’d read eighty books in seven languages—Icelandic, Swedish, Faroese, Norwegian, Danish, English, and Russian. I’d read seventy-five books on the “Top 100” list and decided that was good enough. I felt like the Nordic part of me got a little bit bigger.

That spring, I moved back to Iceland. My third international move in six years. I was looking forward to a bright future. It rained all summer. Although I’d lived in Iceland before, I had to start from a blank page all over again. That was a challenge in and of itself, and I decided to let it suffice.

I got a job selling day trips to tourists in a hotel. It wasn’t what you might call a dream job, but it was work. I spoke mostly English to customers, but started resurrecting my Icelandic with colleagues, rousing it from its deep slumber after three and a half years. The transition from Swedish to Icelandic took a few months—I kept saying [↓j̥͡ɸʷ] instead of [jau:]—and I only swore in Swedish.

I was reading three or four books at the same time—e-books and audiobooks on my phone, paperbacks at home. The stories blended together in my head, I couldn’t get enough of them. I sought out recommendations on the internet and read books that friends suggested. During this book flood, I came across The Law of Attraction. It felt to me like a moment of clarity. It felt like I understood how the universe worked. I was convinced that everything that happened to us was a result of our wishing for it. The day after I finished the book, I was laid off, though I couldn’t remember having ever wished for that. I started looking for a new job. And learning French.

I sent applications to all the local tourism companies, but I wasn’t a super popular applicant with my mere three months of experience. One night, I got a call from a Russian friend. A French acquaintance of his, with whom he’d studied Chinese, was advertising a job in a bookstore—would I be interested? I took it as a sign, sent out wishes and a cover letter that same night. I wrote about my reading challenges and mentioned my interest in French and got the job.

I started working in one of the oldest bookstores in downtown Reykjavík, a place I’d spent a lot of time before I moved to Stockholm. Every weekend, I’d taken my computer and done my homework for university in the coffee shop upstairs. Now, I had a job in the tourist section, where I mostly dealt with the Icelandic flag magnets and keychains at the entrance. The top three questions I received were: “Where is the bathroom?”, “Do you sell stamps?”, and “What’s the price in dollars?”

During lunch breaks, I’d relieve my colleague in the stationary section and brush up on my Icelandic. I learned all sorts of things—the difference between a strokleður (a rubber eraser) and a hnoðleður (a putty eraser), what löggiltur skjalapappír (embossed bond paper) is, and that budda (a coin purse) has nothing to do with Búdda (Buddha). The first time someone asked me about kennaratyggjó—‘teacher’s gum,’ or what’s usually known as “sticky tack” in English—it was an impenetrable riddle and I had to ask the customer for a hint. I hoped that one day, someone would ask me about books.

I waited for that day with bated breath, and while I did, I read all the sample copies in the store. My colleagues gave me a crash course in the contemporary Icelandic literary scene. That year, I read one hundred and thirty-five books, and although I hadn’t set myself any reading challenges, I did set a new record.

*

I started to feel a certain stability. I’d found my footing, though I didn’t feel rooted. Next up was a Slavic reading challenge. I could distinguish between all the Nordic languages, could differentiate various Swedish and Faroese dialects, but I didn’t know what Belarusian sounded like, or whether Poles could speak their mother tongue with Slovaks, like Norwegians could with Swedes.

This journey showed me how languages developed, how they got lost along the way, what things they had in common and what was unique to each one.

It took me nine months to complete my Slavic challenge. By the time I’d finished it, I’d completely forgotten why I was doing it in the first place, but I reminded myself that the journey was more important than the destination. And this journey showed me how languages developed, how they got lost along the way, what things they had in common and what was unique to each one. I now had a broader context for Russian, too. I could feel my Slavic side.

Translation was a logical continuation of my Nordic and Slavic reading challenges. All of a sudden, I felt like I’d arrived. My first attempt was to translate a short story from Icelandic into Russian. It was a new experience, a real joy, a generative intimacy with language. The text was like an x-ray that I was holding up to the light.

That year, I read one hundred and thirty books in sixteen languages. I was neither pleased nor proud of myself, just exhausted. I don’t remember many of the books I read, as I didn’t give myself any time to digest them, was always rushing to pick up the next one. My challenge for the following year was to have no reading challenge. I didn’t want to read anymore, but I just couldn’t bring myself to break up with books.

When the global pandemic struck, I gave myself the space for mindful reading. I was working two days a week and trying to enjoy it while it lasted. I went to the library often and borrowed books in the Nordic languages so as to keep those fires burning. Something ignited within me when I read the poetry of Yahya Hassan, a twenty-four-year-old Danish poet of Palestinian origin, who’d died a few months before in Århus. It occurred to me that immigrant voices weren’t being heard in Icelandic literature. That’s when I set myself another challenge: to change that.

I found a publisher and twelve interested writers and began to work on Polyphony of Foreign Origin. Editor was a new role for me, and I felt like I was sailing under a false flag—all the others were real writers, I was just a bookworm. I hadn’t written poetry before, but since it was my project, I might as well be a co-author. Which is how I came to write my first-ever poems in Icelandic.

I continued to translate short stories that I liked, let myself dream of becoming a translator and started working in the Icelandic section of the bookstore. New books kept arriving and I kept reading them.

That year, I failed my challenge—I read one hundred and fifty-five books. A few times, I started listening to a book I’d already listened to. I felt like I was in a codependent relationship with literature. I was a book addict, I couldn’t stop.

*

In the new year, I registered for a creative writing program in Russia that was taught online. I wrote considerably more and read considerably less. Work on Polophony was in full swing, on top of which, I was taking six classes, working full-time at the bookstore, writing articles in Russian, and translating—all while training to be a Search and Rescue team member. At the end of the summer, I took a vacation to Moscow and, after a mishap on a trampoline, returned home on crutches.

Polyphony of Foreign Origin came out on November 16, the Day of the Icelandic Language. It was my last day at the bookstore before I had knee surgery. I received a box filled with copies of Polyphony, scanned the barcode, put on price tags, set them out for sale. It was like delivering my own child. I hugged my colleagues before I went home. Walked out of the bookstore a published author and editor. “The birth of immigrant literature,” Polyphony was called. “A turning point in Icelandic letters.” I gave many interviews and readings. On crutches and pain killers.

I’m used to being a person of a foreign origin, but I’m not used to being a writer.

That year, I read one hundred and one books. My writing was published in anthologies in both Russia and Iceland. I translated one book. The next year, I took three months’ sick leave as I recovered from my surgery. I wished that this time would bring me another book, and preferably a different job.

I spent my mornings in a coffeeshop near my house that had a nice view of the sea and the mountains. First on two crutches, then on one, then none. After lunch, I translated. I stopped reading entirely. I was keeping a diary and wrote mostly about how it was going with different projects and how I was feeling. The last entry was just a date—February 24—and then a blank space.

*

A month later, I got an invitation to take part in a reading, “Poems for Ukraine,” and so I wrote a few poems for the event. I got a lot of positive feedback on it and kept writing. I was encouraged to submit it for the Tómas Guðmundsson Prize and I decided to make that my deadline for finishing the manuscript. When else was I supposed to finish a book about a war that was nowhere near ending? I couldn’t read—one book a month was an achievement.

I spent the first three months of the war writing my book, helping newly arrived Ukrainian refugees get settled, and got a new job when my sick leave ended. My first book in translation was published in Russia that summer. I received a deposit of $120 that I couldn’t access because my Russian card was blocked due to sanctions. I’d wished to translate a book, but forgot to wish for payment.

When my sick leave ended, I embarked—or limped, really—upon a brand-new life with a book in progress. I asked the universe for the war to end when I finished it, full stop. Then I asked for it to end when the book was published. Máltaka á stríðstímum, ‘Language Acquisition in War Times,’ received good reviews and coverage, was in first place on the Bestseller’s List in my old bookstore. Photos of me, interviews in the media. Strangers congratulating me on the street. And still, the war raged on.

I’m used to being a person of a foreign origin, but I’m not used to being a writer. I don’t know when I became one. I don’t feel like I’ve changed. Now I’m standing at a crossroads, and I don’t know which way to go. There are a lot of doors opening, while others are slamming shut. I want to write prose in Russian, to support the literary scene and readers in my homeland, but censorship is getting in the way of that. I want to write about something other than war, but I’m not sure how. So for now, I’m writing poetry in Icelandic and learning French.

Natasha S. and Larissa Kyzer

Natasha S. wrote this essay for the bilingual collection Writers Adrift, coedited by herself and fellow immigrant author and artist Ewa Marcinek, which will be published by the Reykjavík UNESCO City of Literature Office on the occasion of the upcoming Reykjavík International Literary Festival. The festival will take place from April 19 - 23 and be live-streamed for free on its website. Natasha will be taking part in RILF’s opening night event, in which she and celebrated Icelandic author, poet, and playwright Kristín Eiríksdóttir and American Pulitzer-Prize winner Colson Whitehead will discuss power: who holds it, how it is used, and what structures maintain its status quo.

Larissa Kyzer is a writer and Icelandic to English literary translator. Her translation of Kristín Eiríksdóttir’s A Fist or a Heart was awarded the American Scandinavian Foundation’s 2019 translation prize. That same year, she was one of Princeton University’s Translators in Residence. She has translated poetry, short stories, literature for children, theatrical works, nonfiction, and novels and recently guest-edited “On the Periphery,” a spotlight on new Icelandic writing for Words Without Borders. Her translation of Sigríður Hagalín Björnsdóttir’s The Fires was published in 2023. Larissa is a former co-chair of PEN America’s Translation Committee and runs the virtual Women+ in Translation reading series Jill!