I swung my legs out of bed and stood up carefully. I felt light-headed and hungry, though better than before. I decided to go and scavenge through the bags of groceries in the car, but when I got to the bottom of the stairs, I found a tote bag filled with supplies and a note from Alice saying I’d been asleep when she came and she hadn’t wanted to wake me. There were some cut sandwiches wrapped in aluminum foil, bottled water, painkillers, toilet paper, a toothbrush, hand sanitizer, fresh masks. I held the bag as if it were a bomb. It had been a long time since anyone had made me a care package.

One corner of the barn had been partitioned with plasterboard, and I opened a door to find a basic but functional bathroom with a shower stall wedged next to the toilet. I went to the car to see if I had any fresh clothes. An hour later I was washed, dressed and shaved, feeling cleaner than I had in days, but so tired that I had to go back upstairs to lie down. Almost at once I fell asleep, and when I opened my eyes, the light was failing and the trees were vague black shapes outside the window. I shut them again and woke into another bluish-white morning that smelled of earth and leaf mulch and wood exhaling the moisture of the night.

I sat upright. I felt shaky, empty and insubstantial, but my head wasn’t throbbing and my vision was clear. The little cot above the barn was the first proper bed I’d had since the day Augusto drove me out of the house in Jackson Heights. Sleeping in a car, you’re always anxious about a tap on the windscreen, a flashlight, a hand trying the door handle. Though I’d been traveling for years, and I’d often slept in strange or unfriendly places, I’d been feeling very vulnerable. With a good night’s sleep came a flood of emotions that I found hard to master. I breathed deeply, fighting back tears.

In the car, tucked into the glove box, was a skinny roll of twenty-dollar bills. I’d calculated that I would need to work for another six weeks before I had enough saved for a security deposit. I was thinking about trying Long Island, maybe getting summer work in one of the tourist towns. I was too weak to work construction or landscaping, or any of the other heavy jobs I’d done in the past, and my recurrent bouts of fever and faintness were forcing me towards a question that I’d always known I’d have to answer sooner or later, about what I’d do when I could no longer physically sustain my way of living.

First I needed to get a room, somewhere to stay, then I could think about the rest. Experimentally, I stood up and made my way gingerly downstairs, two feet on each step like a little child. I took another shower, giving thanks for each second of hot water. Since I wasn’t sure when I’d next be able to do better than a public bathroom, I wanted to remember the sensation, the jet hitting my neck and shoulders, sluicing the back of my head. I opened the trunk of the car and dressed, wishing I’d thought to wash some clothes; they could have dried overnight. I rummaged in the bags of groceries for breakfast. Some of the food would have to be thrown away. There was a whole chicken, pieces of salmon, milk, all of it slightly warm. I tore chunks off a loaf of bread and smeared it with runny butter, using a plastic knife from a stash of cutlery and paper plates that I’d swiped from a supermarket salad bar. I wondered what I should do with the rest of it. Most was usable, but company policy was to throw away anything that was returned to the store, regardless of the reason. There were giant dumpsters full of perfectly good groceries, padlocked so that no one would take anything. Maybe if I texted the help desk and volunteered to pay for the losses out of my wages, I’d be able to keep the job.

When I went to make the call, I found my battery was dead. I hunted for the charger and took it upstairs to an outlet, knowing that when I switched it on, I’d probably find it full of angry messages. So I left it and went downstairs and very cautiously opened the barn door, just a crack, staying behind it so I was out of sight. I sat with my shoulder against the door, breathing in the air and listening to the woods, increasingly aware of what wasn’t there, the absence of the high white sound of the city, the screaming at the margins of perception composed of air conditioners and power cables and buzzing fluorescents and the stress of too many people packed into a tight space.

I could see a meandering path leading off up into the trees. There was something perfect about the solitude, the greenish light filtering through the canopy of leaves. A held breath. I imagined walking uphill, subsiding into moss and forgetfulness. Instead, I closed the barn door and prepared to go back out on the road. I cleared out the trash that had accumulated in the car footwells. The interior smelled of sweat and snack foods, poorly masked by a pine tree air freshener. Even if it were vacuumed and steam cleaned, I’d never again be able to use it to pick up passengers; the grime of weeks of occupation would always lurk around the edges, in the window seals and the seat pockets, saturating the upholstery. Though the car was twenty years old, it was mechanically sound, worth the money I’d paid for it. I’d looked after it meticulously, so that even though it barely met the standards of the ride-hail companies, passengers didn’t complain. My star rating had been good.

It’s a fiction we seem to demand, that a person be substantially the same throughout their lives—human ships of Theseus, each part replaced, but in some essential way unchanging. We are less continuous than we pretend. There are jumps, punctuations, sudden reorganizations of selfhood. I’d always had goals, even if they weren’t ones that other people could understand, but at some point I’d lost touch with the person who’d set them. If you had asked me what I was doing, delivering groceries in upstate New York, I would only have been able to give you a superficial answer.

Clearing out the car was tiring, and I went upstairs to rest. I drifted off to sleep and woke again to find that it was dark and a voice was calling my name.

“Jay? Are you OK?”

I sat up groggily and fished around for a mask.

“Yeah. I’m fine.”

“Can I come up?”

“Just a moment.”

She climbed the stairs. She was dressed in athletic gear, leggings and a long-sleeved top, her hair tied back in a ponytail under a cap. Her mask was the same dusty orange as her shoes. Looking at this precisely matched outfit, I wondered again who this woman was, who she had become. When we were together, her primary form of exercise had been walking to the shop.

For a while we exchanged awkward small talk, like people who’d met at a boring party and were making the best of it. I told her I was getting ready to leave, that I needed to get back to my job. She said I didn’t seem healthy enough to work.

“This can’t be the first time this has happened to a driver. Call them up, sort it out with them.”

“It’s an automated system.”

“So? There must be people.”

It was hard to explain to her. She was a rich person, used to interactions in which she was respected, even courted. On the rare occasion when her status wasn’t recognized—by some official or service provider—it was, I imagined, a memorable outrage. She’d find it hard to understand that I had no relationship with the company outside terms set by the app. It was designed that way. Even if you stayed on the phone for hours and finally got to speak to someone in a faraway call center, they had no agency. You could never appeal to anyone’s humanity.

“Is someone waiting for you?”

I hesitated, confused by the change in direction. “No.”

“Well then.”

“It’s not that simple.”

“I just don’t see why you’re leaving. If you’re anxious about money, we can work something out.” She stood up. She seemed irritated.

When I first met Alice, I wanted to devour her. I wanted to exhaust her and exhaust myself, wear us both out until there was nothing left. I understood, in a confused way, that what you can see of other people, what they let you see, is only the part of the iceberg that’s visible above the water. When I was young I thought of that as a challenge, a mystery to be explored. I would reflexively try to “get to know” everyone I met. Gradually, the purpose of this deep-sea diving began to seem less obvious. What is the point of knowing people, really? What does it achieve? We try and touch each other, but it is impossible.

Alice started down the stairs, then turned.

“If you’re leaving in the morning, you’re going to need me to open the gate. There’s a code. I’ll come by, I don’t know, around 9:30, OK?”

“Sure.”

She hesitated.

“So where did you go? Where have you been for all these years?”

I shrugged. “Traveling.”

“Have you been making art?”

“I don’t really make anything.”

“Nor do I.”

I stared at her, trying to gauge what she meant. The mask made it impossible.

“What do you do, Alice? I always assumed you’d be writing books, running a museum.”

She laughed, a clipped little percussive sound. “I clean up Rob’s messes.”

She broke eye contact. She cuffed her wrist with the fingers of her other hand, rotated it a couple of times, then let it drop. The familiar sequence complete, she looked back up at me. “How about you?”

“I just do whatever the app tells me to.”

It was meant to be a joke. The pause that followed was broken by the sound of her phone.

“Hello?”

I noted a slight tension in her voice. As she answered, she instinctively took a few paces down the stairs.

“Hey you. Oh, I’m just out for a run.” She went a little further down. “I know it’s dark. I just wanted to be out of the house.”

So I was still a secret from Rob. I tried to ignore the little hit of satisfaction this gave me. I wanted to feel nothing, to remain unmoved. Instead, rusty emotional gears were beginning to turn, and I found myself setting out on a familiar elliptical orbit.

Alice’s voice rose sharply in response to some question.

“My God, whatever you want there to be! Just look in the fridge, use your imagination.”

__________________________________

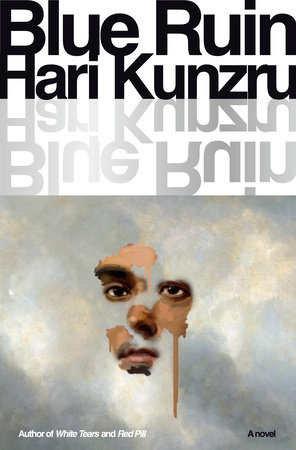

From Blue Ruin by Hari Kunzru. Copyright © 2024 by Hari Kunzru. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.