Blowing Up Bungalows to Make Way For Airports

On Another Kind of Urban Displacement in Atlanta

My parents met us for dinner at a Thai restaurant in Hapeville that overlooked the airport. While there is no airport-sanctioned public observation deck, a few balconies along Virginia Avenue offer a glimpse of the swarming activity on the tarmac. Between mid-rise hotels, white planes with dark fins roll silently along a distant taxiway. Curious little vehicles swarm in the dust clouds left by landing aircraft.

As we waited for our meal, Dad leaned over to Gayle and asked, “What does that remind you of?” He pointed to a crumbly strip of concrete below.

She smiled. “Going to the airport.”

Jason and I examined the mysterious strip and its twin across the street. They were about fifty yards long, unmarked, overgrown with weeds, and disconnected from any roadway. My parents have done this as long as I can remember—shared inside jokes and memories at the dinner table while we tried to guess what they’re talking about.

Eventually Dad explained that we were looking down on the former entrance to the Atlanta Municipal Airport, the dramatic symmetrical ramps that led to the old terminal. I couldn’t understand why the entrance and exit ramps remained. Why were they left behind? Everything disappears in Atlanta, why not those lackluster remnants?

The entire Atlanta Municipal Airport would fit in one parking lot of today’s Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport. The whole thing was gone, but for some reason the entrance and exit ramps survived. Cut off and floating, they led nowhere and served no purpose. What planning oversight or sentimental urge allowed them to remain? The remaining concrete was like part of a secret map, visible only from the air.

I asked my dad if he was a frequent flyer in those days. He thought that was funny.

“We were always picking someone up or dropping them off. I didn’t fly for the first time until I was in my forties.”

Watching planes at the Atlanta Airport was a legitimate date activity for a whole generation of Atlantans. Then he told me about “Blue Lights,” a notorious destination for teenage necking on the College Park end of the runways. The long stretches of pavement were marked by low blue runway lamps, and virtually unsupervised.

I did the math. As Forest Park natives, Dad and Gayle grew up with the airport, but it was the 1990s before they ever actually flew anywhere. By then, it was a completely different airport—new name, entrance, tower, and terminal. It had become a place equipped to handle four times the passenger volume, and that volume included the very residents it had displaced.

I was seated next to the window, uncomfortably warm as the sunset glare baked my cardigan, but I kept it on. The square of gauze taped in the crook of my elbow was left from a routine blood draw. My parents would notice it and ask about it and I still hadn’t told them anything about being pregnant. I wasn’t even admitting it to myself.

It had taken two years and two miscarriages to get this far along in a healthy pregnancy. When we started trying to get pregnant, I couldn’t imagine the hormonal wilderness ahead. According to Facebook, it seemed like all my girlfriends had such a pleasant time having babies.

Meanwhile, miscarriage is death without ceremony. No funeral, no name. No one would ever tell you, for example, if your mother died, that mother-death is actually quite common, hang in there honey, you’ll find another mother. The angst of miscarriage lingers, maybe even multiplies, because you’re the only one who knew the deceased, and the way you knew them was theoretical, fleeting. You conjured them into existence, only you conjured poorly and it is probably your fault the spell failed.

The first thing people ask is, how far along were you? As if to measure the loss. A couple of months for me each time, but it was years of plotting, taking jobs, situating rooms and relationships, hours and dollars. Adding insult to injury are the relentless announcements and baby showers, the perils of visiting a Target at 10 am on a weekday. Pregnant friends everywhere, as if generated by my own misfortune.

Two losses in a row put me in the mode of self-protective detachment. It wasn’t until after the first trimester, after a high risk, high-res ultrasound at thirteen weeks showed not only “a keeper” but a healthy baby boy, that I began to consider that this was a potential family member I was ignoring. The doctor said, “Try to have fun. Try not to worry.” But I was grim as I called my family to tell them the news, cutting off any celebration or questions. Even so, my mom sent me a blue teddy bear and flowers the next day.

Sorry kid, but your first few weeks of existence were a time of profound silence and dread. Instead of creating my baby registry, I was digging through county deed records, verifying rumors and stories about the airport. I carried you with me to all the ragged edges of the runways. You were acclimated to plane noise before you were born.

*

I heard so many stories of villainous airport encroachment, even legitimate accounts began to sound like conspiracy theories.

I heard that the airport was built on top of the Flint River, or the headwaters of the river, which is Georgia’s second longest and a major southeastern watershed. This turned out to be true. Though it resembles a drainage ditch where it meets the northern runways through a supersized pipe, by the time the Flint emerges on the south side of the world’s busiest airport it looks like an urban creek winding through a forest. It’s a place where the brave might dig for crawdads or garnets, though not yet deep enough to canoe.

The shallow bowl of the Flint River basin was the ideal terrain for a racetrack, which later became Candler Field, then Hartsfield-Jackson airport. Channelized and buried since at least the 1960s, the secret Flint River is both a marvel of engineering and a metaphor for the area’s hidden soul. As the airport grew up around it, the ancient river continued silently on its way to the Gulf of Mexico.

I heard that the airport once tried and failed to convert Virginia Avenue, the main commercial strip north of the airport, where Thai Heaven is located, into a runway. This is false. Having steeped myself in airport master plans, I knew this didn’t make sense, but I could understand the basis for rumor. From shifting Interstate 85 to erasing the entire City of Mountain View to building a runway on top of I-285, wilder things had happened during the climb to aviation dominance.

For College Park residents, these were not rumors, but a genuine existential threat. The College Park Historical Society was formed by concerned residents in 1978 to fight northward expansion of the airport. That same year they would have been watching events in Mountain View unfold—the mayor on trial, scores of houses lined up on flatbed trucks, the scandal in the newspaper: “City Charter Revoked.”

Over the next two decades, they succeeded in registering 850 houses and the Main Street commercial corridor on the National Register of Historic Places, creating one of the largest historic districts in the state and protecting the core of College Park from further threats. They successfully fought off proposals for flight vectors that would aim additional air traffic over their homes, plus round-the-clock cargo flights that would generate noise through the night.

In the same way, over the last decade I have found countless groups of Airport-area exiles who congregate on Facebook to post black-and-white class photos and front yard snapshots. Their posts are tiny acts of historic preservation, just trying to remind each other of what the neighborhoods looked like before they were absorbed by the airport.

Meanwhile, the airport continued to acquire vast swaths of College Park neighborhoods under the flight paths for purposes other than runways and aeronautical uses. These not-so-historic places met their ignoble ends as airport parking lots, a rental car center, and a gigantic convention center.

I heard one story that sounded so preposterous, I thought it must be a rumor. A friend from high school told me that a Chuck Norris movie was shot in College Park in the 1980s and the filmmakers blew up a whole neighborhood of airport-owned houses. This friend was working in the film industry and he heard the story firsthand, from a guy who participated in the production. That’s the only reason I didn’t dismiss it immediately as a paranoid urban legend.

It turned out to be true. Invasion USA was a 1985 low-budget action thriller filmed in several Atlanta locations, including a battle scene downtown involving tanks on Peachtree Street. According to online movie trivia, the Soviet terrorists in Invasion USA blew up several houses near the Atlanta Airport that had been slated for demolition due to runway expansion.

I found this neighborhood attack scene online and advanced slowly through the footage to look at the houses. It was an intersection that looked like any early 1960s neighborhood on the southside—modest brick ranch houses notched into a hill, surrounded by full and towering pines. They had picture windows with white shutters and long driveways and carports where station wagons and boats were parked. The scene was shot at night, presumably on Christmas Eve, and their eaves and holly bushes were loosely draped with strings of red and green bulbs.

The scene opened with an instrumental version of “Hark the Herald Angels Sing” as a pack of kids scampered from their bikes to their front doors for supper. The music shifted to a sinister synth soundtrack as a large pickup truck rolled into the frame. Two bad guys wearing goggles stood in the back, one blonde, one masked, passing a bazooka back and forth and taking aim at the houses.

The first blast jogged the camera. Blurry extras ran screaming as the house exploded. In slow motion, the fireball hurled an entire door, still attached to its jamb, across the yard. A ladder toppled away from a Christmas tree. The terrorist grinned, pivoted, and fired on more houses. It appeared that he detonated at least eight of them before patting the top of the pickup truck and signaling their work was done.

I couldn’t bring myself to watch the rest of the movie, so I have no idea what led up to this perverse scene, or what happened afterwards. I assume it sets Norris up to unmercifully punish the bad guys. An attack on suburbia on Christmas Eve is an intentionally disturbing scene, but it made my stomach hurt for different reasons. While most airport homes were unceremoniously demolished, the near-pornographic destruction of this corner of College Park is stashed on YouTube for all to witness.

I can’t believe this happened in 1984. I thought this kind of scorched-earth urban renewal ended in the 1960s.

The production crew didn’t bother to change the street signs, so I was able to freeze on a frame that included a tiny “First Ave” sign and then locate First Avenue on a 1969 airport map. First Avenue was on the southwest side of the airport, near a subdivision called Newton Estates. I zoomed into an odd, triangular intersection that matched the footage. The airport’s rental car center covers it now.

Searching for Newton Estates in the airport’s environmental records led me to a remarkable document, The Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport Noise Land Reuse Plan. It was an enormous and formal report, consisting of two hundred low-quality scans of legalese, maps and charts. It explained the FAA’s methodology for measuring decibel levels near the airport as “day night average sound levels” or DNL. The worst affected areas were within these “noise contours.” The runways were circled in red for greater than 75 DNL, the highest noise level. The yellow 70-75 DNL contour spilled out beyond the runways to the east and west into College Park and Clayton County. The green noise contour, 65-70 DNL was a blob that nearly swallowed the southside. Within these boundaries, the airport could apply for federal funds to buy out residences, churches, and other “incompatible uses” on designated “noise land.” These were the lines that determined where people could live.

Most fascinating to me were the hundreds of spreadsheets detailing every single parcel acquired by the airport from the early 1980s through 2009, including the purchase price, date of transaction, and the source of federal funds used to make the purchase. I knew that every single line of data represented a family, a business owner, or a pastor seated across from a team of attorneys at a closing table. Each line on the spreadsheet marked a turning point.

My home in Mountain View was nowhere to be found in these records. It was part of a pilot program that preceded the airport’s official noise mitigation efforts, early attempts to stem residential complaints about the racket. Also missing were the huge swaths of College Park, Riverdale, and other neighborhoods that are underneath the runways and terminals today. Only those useless parcels designated as “noise land” were documented in detail because the airport would eventually need to “dispose” of them and convert them into “compatible uses” like warehouses, parking lots, and light industrial uses.

I studied the document into the early hours of the morning, pondering the scale of the Hartsfield-Jackson’s kingdom. How could this land acquisition program be so enormous, so obvious, and yet so misunderstood by the people who lived there? It was upsetting to think that the relocation of Mountain View was not an isolated undertaking, a thing of the past, but an ongoing, continuous campaign. The transactions seem to peak in the mid 80s, but airport buyouts continued through the next twenty years.

I found the First Avenue parcels used in Invasion USA in the airport’s Noise Land inventory. Scrolling through the pages and pages of transactions is strange and unbearable, but I did it. I counted 571 residential transactions in this area alone. Closing dates clustered around 1984, 1985, and 1986, which means that during the production of the film, this area wasn’t completely vacant. While the buyouts were still in progress, high-powered explosives were violently shaking the neighborhood. Invading, indeed.

Chuck Norris has a sufficient cult following to have merited a short documentary called The Making of Invasion USA. In it, the director, dead-eyed in a pink Hawaiian shirt, boasts, “We did, in fact, really destroy the neighborhood.”

There was some B-roll footage of the crew decorating the outside of houses with tinsel and lights in their final hours. The interior shots of pyrotechnicians rigging one house with mortars were even more poignant. Here were rooms from 1984 that matched a whole catalog of ghost houses from my childhood. A quick shot of patterned linoleum in the kitchen, a dark floor register in the carpet, candy pink tile in the bathroom. I watched this part in slow motion.

*

A month later, on a Friday night after work, Jason rode MARTA a few extra stops to meet me at the airport for a date. I waited by the entrance to the train station. The orange sodium lights and abrupt end of air conditioning signaled that you were leaving the airport, trading one mode of transportation for another, less comfortable one.

We were there because I wanted to see the photo exhibit commemorating the 30th anniversary of the new “midfield” terminal. It’s an entirely different experience to visit the world’s busiest airport when you aren’t determined to catch a flight or locate an arriving traveler. It reminded me of going to a mall at Christmas—lots of people, very focused and hustling.

Instead of looking at the massive overhead “Arrivals and Departures” board, you might observe the virtuosity of the piano man at Houlihan’s Bar & Grille. Without hurrying towards your gate, you might notice the small tribe of homeless men taking advantage of the facilities. When you’re not a captive audience, you might think twice about the price of candy. It’s like $3.99 for a bag of Sour Patch Kids.

The “exhibit” consisted of a few photos and architectural renderings mounted to the pillars of the grand atrium. As we cruised around the columns, taking photos of photos, reading the captions aloud to each other and generally giggling and acting amused, a few busy commuters paused to assess the exhibit. It’s hard to explain why we found it so entertaining.

Maybe because the airport has been such an enormous presence in our lives, and this was like a rare chance to view the family album. Mayor Maynard Jackson and his wife Valerie were there, cutting ribbons alongside a baby-faced Governor Jimmy Carter and the young Shirley Franklin, who would go on to become mayor. The CEOs of Delta and Eastern were posed in a moment of rare camaraderie.

At the anniversary ceremony, George Berry, who served as general manager during the transition, made a speech:

That day had to be one of the high points of all our lives, every one of us who worked on it, dreamed about it, and who thought that being a part of such a dramatic undertaking would be something that would mark us for the rest of our lives—and it has.

I wrote down the date: September 21, 1980. This date must have marked my life too, and the lives of most southside residents, in ways that are hard to estimate. It meant the official end of many residential communities around the airport.

The exhibit did a good job of comparing the airport before and after this grand opening ceremony, making a case that the enormous new airport was inevitable. Both the 1961 and the 1980 terminals were the biggest, most advanced airports of their day, and both assured Atlanta’s ranking as the busiest passenger airport in the world. The original airport, as described in Air Castle of the Jet Age was “all sparkling blue and white… spread out like a giant fiddler crab in that sea of asphalt and concrete.”

Designing for maximum efficiency, terminal engineers took it as a compliment when Paul Goldberger, architecture critic for The New York Times, wrote, “it is hard not to get over the sense that one is caught in a huge machine, something like a great Xerox machine.” Unlike the “jet age” generation of airports, which served as a hopeful, symbolic gateway to a city, this new terminal was designed to accommodate the high volume demands of transferring passengers and cargo.

A series of promotional photos showed the new terminal in all its vacant glory. Before, it was all glittering tile, potted plants, and “The Oasis Lounge.” After, the Xerox machine welcomed travelers with acres of burgundy carpet, molded plastic chairs, and chrome. Lots of chrome.

*

I found a July 1984 home movie of the original terminal demolition that someone posted online. The Super-8 footage gave everything a golden haze. The scene opened on blue sky with a buzzing sound, as if air traffic continued amidst the planned implosion. The new control tower was already in use and construction on the fourth runway was underway. The camera focused on the 1961 tower, rigged with explosives. It was a delicate puzzle box of alternating stripes—aqua windows and blue curtain wall—crowned with a glass turret. The building anchored a series of high-flying arched pavilions.

There was a wobbly 360-degree pan, as if the cameraman was just killing time before the countdown. The tops of people’s heads. Block letters on the adjacent building spelled out FLY EASTERN AIRLINES. In the foreground, the crowd shifted. They stood by their cars. Then the news helicopters moved out of the frame.

Back to the tower. The faint chant of a countdown could be heard. At zero, the implosion began. It sounded exactly like the sound effect for thunder in a cartoon. As the crash subsided, the building slipped down evenly behind a rising wall of dust. It looked two-dimensional, like a plywood stage prop lowered behind a set. About four seconds is all it took.

Cheers. Applause.

“Aw man,” a voice off camera said. “It just disappeared didn’t it?”

Cut to a helicopter drifting through the dust cloud. Chatter and whoops from the crowd. A woman’s nervous laughter. Pulverized concrete bloomed out toward the parking lot.

Cut to the dust cloud, now from a distance. Small figures moved to their cars.

*

Jason and I picked over our Styrofoam plates of ten-dollar chow mein; I had recently learned that noodles were one of the few foods I could tolerate. As we watched people milling in the food court, I considered our date night at the airport a southside tradition. For generations we have come to these grounds for romance and adventure, either anticipating a flight, parking at “Blue Lights,” or watching the planes takeoff. That fuzz of hopeful pre-flight anxiety happens at the airport even when you’re not traveling.

Maybe it was the weight of the pregnancy, but I was glad not to be going anywhere. It was calming to be a stone in in the river of travelers. I kept my eye on the homeless and runaways wandering these halls, just here for the scenery.

_______________________________

Feature photo by David Naugle.

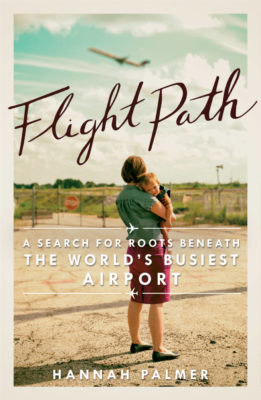

From Flight Path: A Search for Roots Beneath the World’s Busiest Airport, courtesy Hub City. Copyright 2017 by Hannah Palmer.

Hannah Palmer

Hannah Palmer works as an urban designer in Atlanta. Her writing explores the intersection of southern stories and urban landscapes, and has appeared on CNN.com, Art Papers, Creative Loafing, and in masterplans for urban design projects around the world. She earned an MFA in creative writing from Sewanee: The University of the South and now lives near the Atlanta Airport with her husband and sons.