Blackness on the Margins: What Ann M. Martin Asked of Jessi in The Baby-Sitters Club

Chanté Griffin Considers Black Characters Then and Now

I remember the day my boxed set of the Baby-Sitters Club books arrived. It was my sixth grade culmination and I was adorned in my Sunday best: a flower dress my mother had sewn that was covered with pink and lavender flowers; cream stockings; and black patent leather heels. (They were my first pair of heels, and you couldn’t tell me that those one-inch block heels didn’t make me look grown and gorgeous!) After the ceremony and the obligatory photos with my familial entourage, my teacher, a blonde white woman with short hair, came running toward my family, arms flapping to get my attention: “These just arrived in the mail!”

Reading the books that summer felt like as much of a treat as the cherry-flavored popsicles my little sister and I licked in the California sunshine. In my mind, Kristy, Mary Anne, Stacey, and Claudia were my BFFs, even without the matching heart necklaces to prove it. When Mallory and Jessi joined the club, I embraced them too. But something didn’t sit right with me about Jessi, even though we both had moved to neighborhoods and schools where we were suddenly one of the few Black kids; and even though we both were experiencing racism for the first time at those schools.

As an 11-year-old, I couldn’t articulate what I now recognize as an adult: that the series’ depiction of Jessi’s racial identity lacked the kind of cultural sophistication I needed as a young reader, particularly as a young reader who was Black. In some ways, Jessi’s inclusion in the series was ahead of its time given the lack of diversity in children’s and young adult literature. In other ways, it was also painfully reflective of that time.

It’s challenging to offer a critique about a writer whose books you loved as a kid, really difficult to highlight what she got wrong when you know that she tried hard to get it right. I’m tempted to skip over certain words like little girls skip over certain squares in hopscotch—just to spare her feelings. Although I wish that race would’ve been handled differently in the BSC series, I appreciate that it was addressed. For example, my heart leapt when Jessi received the role of Swanilda despite her concern that the town’s racism might prevent it. As a former commercial model, I know what it’s like for casting notices to say “sorry, no Black girls,” or “light-skinned Black women only.” I know what it’s like to read those notices, to feel pain, and to grieve that I won’t be selected. So when Jessi won the coveted role, my tear ducts filled with pride and relief. Even while rereading the book as an adult.

My angst with Jessi’s character, though, started with her introduction in Hello, Mallory. Although Mallory initially describes Jessi as “beautiful,” noting that ”She was long-legged and thin, and even sitting down she appeared graceful,” Mallory also adds: “Also, she was black.”

“Wow,” Mallory tells us, noting how few Black students there are in her school. “This was pretty interesting.”

While my 11-year-old self knew only that she didn’t like that Jessi’s presence was “interesting,” my adult-self realizes that I wanted to meet Jessi first, and any ensuing racism later.

I know what it’s like for casting notices to say “sorry, no Black girls,” or “light-skinned Black women only.”

Throughout Hello, Mallory, it becomes painfully obvious that to some of the residents of Stoneybrook, Blackness was the black elephant in the room that they didn’t know how to address directly, but that sometimes loomed as a source of discomfort. This was true even for Mallory and her more progressive family, who welcomed Jessi in ways their neighbors didn’t. Mallory and Jessi’s discussion about the racism Jessi was experiencing in town particularly stood out:

“I don’t belong in this school, or even this town. Neither does my family.”

“You mean because you’re, um . . .”

“You can say it,” Jessi told me. “Because we’re black.”

This conversation was difficult for me to read as a preteen and as an adult. While I understand that the point of this scene was to bond Jessi and Mallory and to discuss a critical issue, I wanted it to play out differently. As written, it suggested to me that being Black was a taboo topic that Mallory couldn’t address directly. I’m saddened that 11-year-old Jessi had to coach her future BFF on how to talk about race. I’m saddened, too, that when she met Mallory’s mom for the first time, Jessi had to endure her surprised (wow, I didn’t expect a Black person to walk in) look. While Jessi would go on to enter that home innumerable times without incident, that introduction remained etched into my 11-year-old mind.

When Jessi introduces herself at the start of each book she narrates, she notes that she is “black” or “African American.” For example, in Jessi’s Secret Language, after she introduces her mom, dad, little sister, and brother, she tells us: “My family is black. I know it sounds funny to announce it like that. If we were white, I wouldn’t have to, because you would probably assume we were white. But when you’re a minority, things are different.” Yes, it did sound funny to my 11-year-old self, as I never thought that my Blackness was worth stating, not even to my sixth-grade pen pal, who had never met me because she lived in another state. Every time I read Jessi’s self-descriptions, I felt uncharacteristically self-conscious about my race. Jessi’s incessant labeling of herself as Black, coupled with her explanations about why she needed to, left my preadolescent self feeling unsettled and pushed to the margins.

Every time I read Jessi’s self-descriptions, I felt uncharacteristically self-conscious about my race.

Looking back I realize that Jessi’s identity was steeped in race in ways the white characters’ identities weren’t. Back then, however, I didn’t have the words to describe the discomfort I was experiencing or questions to challenge Ann M. Martin’s logic: Were protagonists assumed to be white? If so, were they presumed to be white only by white readers or by all readers? Was Martin making Jessi accommodate the white gaze? In her 2016 article “The Pervasive Whiteness of Children’s Literature: Collective Harms and Consumer Obligations,” Brynn F. Welch writes that “the pervasive whiteness” of children’s literature feeds the idea that “white is the norm or default while other races are variations from that norm.”

An example she cites is how skin color gets described in many children’s books: “White skin is the default and as such requires no special attention. Deviations from this default, however, require comment or explanation.” This explains why I felt uncomfortable every time Jessi said “I’m Black,” “We’re Black,” and “You should know that we’re Black.” All of those statements clearly—even if unintentionally—positioned Jessi as outside of the norm. (Claudia’s descriptions mirrored this pattern, too.) Kristy, Mary Anne, Stacey, Dawn, and Mallory were never similarly burdened with describing themselves as white. They lived fictional lives unburdened by race.

Welch observes that “race often defines characters of color.” It’s this aspect of Jessi’s construction that my 11-year-old self intuitively disliked. Because her introductory story into the series and resultant self-descriptions conspicuously centered her race while unintentionally positioning her on the margins, being Black, then, became a plot point she could never escape, despite her varied babysitting adventures.

Neither could Jessi escape the stain of racism that can subtly vilify its victims more than its perpetuators. For instance, in Jessi’s Gold Medal, she tells us: “People have gotten used to us (doesn’t that sound weird?).” Yes, Jessi, it does! Here, Blackness gets positioned as the thing that needs to be gotten “used to.” As if it were somehow problematic, instead of people’s attitudes. As if being Black and the dirty racism against Blacks are imperceptibly intertwined. As a result, Jessi’s Blackness is either something to be whispered about, ignored, or overcome, and being Black is simultaneously an unmentionable stain and an always-mentioned stain that parenthetically sullies Jessi’s intelligence, discipline, and babysitting badassery.

Looking back, I recognize that I wanted Jessi’s stories to be “culturally conscious,” a term author Rudine Sims defines in her book Shadow and Substance. Sims explains that culturally conscious stories integrate a character’s universal experiences with her race and culture. In the BSC, this happens only too rarely. For example, to me the best part of Happy Holidays, Jessi isn’t the exploration of Kwanzaa but rather the matter-of-fact pecan pie mention.

When reading about the Ramseys, I wanted to witness more details like that, details that celebrated Black life and culture in daily life. I wanted Jessi’s race and culture to be seamlessly integrated into her life and babysitting adventures, and not just used as story plots. We could have seen Jessi endure a marathon-braiding session with her mom in preparation for her synchronized swimming classes. Or watched her travel to another city to have a Black hairstylist braid her hair if her mom didn’t know how (because obviously nobody in Stoneybrook would know how to braid extensions). Either would have rung as authentic and affirming for me and other readers like me. Seeing Jessi’s cultural context—my cultural context—would’ve helped me feel known, seen, and celebrated while reading the series.

What the 11-year-old me wanted, too, was not just for African American culture to be celebrated in the BSC, but for Blackness to be centered: for Black skin to be as unassuming as white skin, to make no accommodations for the white gaze. The late Nobel Prize winner Toni Morrison mastered this: introducing readers to Black female protagonists who were not necessarily physically described as Black yet exuded a cultural consciousness that showed readers they were. While perhaps it’s unfair to compare kids literature to fiction crafted by one of the most celebrated writers of our time, I mention Ms. Morrison because she refused to write Black women the way they had been written about in an industry that centered whiteness. She broke the broken mold, and created a new one.

I recognize that Ms. Martin too broke the mold when she wrote teen and preteen girls as ambitious, talented, multifaceted businesswomen. Yet she missed an opportunity to challenge norms about how Black characters were written in YA and children’s literature. When Jessi was first introduced for readers, Martin’s description could have included a description of Jessi’s brown skin, without the racial tag, and she could have described the skin of white characters so that all characters received equal treatment under the pen. Similarly, Jessi’s beautiful description of her father’s laugh in Jessi’s Gold Medal, which she described as “deep and booming,” and “sort of like James Earl Jones, the famous actor,” could’ve stood alone, without adding that he was Black.

The painful irony is that, even as Martin tried to dismantle the pervasive whiteness of children’s literature by including Jessi in her series (not to mention the ever-chic Claudia Kishi), in book after book after book, Jessi bore the brunt of accommodating that whiteness, even in her own character’s POV. In book after book after book, I too was made to bear the brunt of the pervasive whiteness of children’s literature: each supposition to Jessi’s “difference” was unmistakably a supposition to my own.

What the 11-year-old me wanted was not just for African American culture to be celebrated in the BSC, but for Blackness to be centered.

Looking at Jessi’s character now, it’s clear that she was a glimmer of what was to come in YA and children’s literature: young, gifted, and Black characters who fully reflected their racial and cultural heritage without being unduly defined by it. Jessi came before Black female protagonists like Jade (Piecing Me Together, 2017), Starr (The Hate U Give, 2018), and Natasha (The Sun Is Also a Star, 2019), all written by Black women writers. But these protagonists would emerge only after the publishing industry was called out for its lack of diversity. At the 2014 BookCon, an event sponsored by BookExpo America, the lineup of children’s authors featured 30 white authors and one cat. There were zero writers of color. Zero. Backlash quickly ensued, and the #WeNeedDiverseBooks movement emerged, pushing for diversity in children’s books.

A study published by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center highlighted the disparity. Analyzing the 3,200 books their library received in 2013, the study found that only 93 (2.9 percent) of those books were about Black characters, 69 (2.2 percent) were about Asian Pacific Americans or Asian Pacific Islanders, 57 (1.8 percent) were about Latinos, and 34 (1 percent) were about American Indians. The remaining 2,947 books (92.1 percent) featured either white characters or animals. Let that sink in.

More than 30 years after Jessi’s babysitting debut, the need to advocate for more diverse stories, including nuanced stories about Black women and girls (especially those written by Black women), remains.

Thanks to Twitter activism, it’s becoming increasingly difficult for the publishing, TV, and film industries to avoid telling a multitude of stories starring a diverse cast of characters. The emergence of the seemingly perennial #OscarsSoWhite hashtag, coupled with the #ownvoices hashtag—which supports kid lit about diverse characters written by authors from that same marginalized group—has brought increased attention to the need for diversity on the page and on the screen. As a result, more talented, underrepresented writers are flooding readers’ pages and screens. Jamaican American author Nicola Yoon’s The Sun Is Also a Star, a love story about a Jamaican-born girl and a Korean American boy falling in love as she seeks to avoid deportation, was so popular that it was adapted into a feature film, as was Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give, which explores police shootings of unarmed Black men.

Of course there have always been talented Black women writers penning tales worthy of the page-to-screen honor, just like Martin’s series; but for centuries, closed doors have often excluded them from high-profile publishing opportunities. This lack of inclusion and celebration led to the creation of the Coretta Scott King Book Awards in 1969. Its website states that it honors “outstanding African American authors and illustrators of books for children and young adults that demonstrate an appreciation of African American culture and universal human values.” It’s important to note that the Coretta Scott King Book Awards celebrated Black writers and Black stories—before Twitter hashtags demanded diversity in children’s literature and before the Newbery Medal Selection Committee gave its top prize to its first Black author in 1975.

As efforts to diversify children’s literature have gained momentum, particularly over the last five years, more Black authors have received their just due, including honors from the Newbery Medal Selection Committee, which typically lead to increased sales and national recognition for its acclaimed authors. Recently, 2020 was a stellar year for Black storytelling as The Undefeated by author Kwame Alexander and illustrator Kadir Nelson and Genesis Begins Again by author Alicia D. Williams became 2020 Newbery Honor Books. That same year, the Newbery Medal went to Jerry Craft’s graphic novel New Kid which follows the life of seventh grader Jordan Banks as he navigates life on the margins at a prestigious private school.

One of my personal favorites is Renée Watson’s Piecing Me Together, a 2018 Newbery Honor Book and recipient of a Coretta Scott King Book Award, which portrays Jade, a high-school-aged collage artist navigating her identity as an artist and new student at a prep school across town. Watson shows how Black culture, plus racism and sexism, permeated every part of Jade’s life: from where she ate, to the artists she studied. But, unlike Jessi, her Blackness didn’t loom ominously over her. It was simply a foundational truth from which her life and art bloomed. Jade bravely pieced together an identity that fused together the best and worst that life brought.

Books like Piecing Me Together and New Kid are giving young Black readers the gift of seeing themselves alive in print as beautiful, complicated, thriving beings. Yet I understand that all kids need diverse books, not just Black kids. “Because of the long shadow of racial segregation,” Welch writes in “The Pervasive Whiteness of Children’s Literature,” “many Americans will learn about people of other races from second-hand representations. Consequently, the second-hand representations are powerful, especially for young children, because these early representations can shape lasting impressions.”

As a writing and literature coach, I teach my students not to just consume a diversity of good books, but also to critically unpack the literature they consume by asking: Do I identify with this? Why or why not? Whose perspective is centered in this book? What works? What could be different? How? I hope my students will know that their lives are worth being reflected back to them, that their stories are worth being told: stories about their Blackness, stories unrelated to their Blackness, and stories that reflect their cultural heritage. Ultimately I want them to find protagonists that they can hold in their hearts for a lifetime, just like I hold Kristy, Mary Anne, Stacey, Claudia, Dawn, Mallory, Jessi, and Jade in mine.

___________________

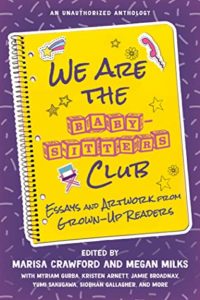

Excerpted from We Are the Baby-Sitters Club, edited by Marisa Crawford and Megan Milks, courtesy of Chicago Review Press. Essay copyright © 2021 by Chanté Griffin.