Blackness Beyond America: Shayla Lawson on Global Conceptions of Black Identity

“We don’t just need the summary version of the diasporic experience, we need every story.”

Featured image: Brandon Mushori/Wikimedia Commons

Harare, Zimbabwe

Farai is drinking Zambezi lager behind the wheel of an evergreen Acura at three o’clock in the morning. I’ve been in Harare less than a couple of hours. The sky is pitch, anticipating the day as a vision of itself rising up again. Meaning: somewhere over on the glint of the horizon there’s the gold-pink seam of a new day breaking upon New Dispensation, a new political regime and the end of Mugabe’s thirty-seven-year reign, which began just a few weeks before I arrived in Harare. But tonight, in the sticky bucket seats, with the windows rolled down, our driver is drunk and the four of us are looking for a place that’s still open to dance.

Farai, the driver, I’ve just met for the first time, but he’s the friend of the Zimbabwean PhD student I followed back to her home during winter break. I finished graduate school two years ago but we always vowed one day we’d go back together. Or maybe she dreamed, and I promised; that’s how I ended up traveling around the world: I hear What if, I say, Let’s go. In my mind, I’ve already done it. In my mind, I’ve already conquered the heat of Harare before we’ve even planned the trip.

*

There was something about that first drive in the dark in a new place that felt fresh, despite the peril. At home, it was December 2017, the first year of the Trump era, and I felt liberated to have someone reckless in charge of my fate instead of the careful way I’d grown accustomed to living in the United States. I did my taxes. I buckled my seat belt. Everywhere I walked in America, I strapped myself carefully in. It was nearly January, the tension in my liberal home city hitting its dark edges, like the stiff crunch of crisp dead leaves.

When the world prioritizes our images of freedom above all others, the big “B” in Blackness becomes America’s way of marginalizing everyone else.

I’d spent the better part of Trump’s presidential pursuits covering his rise to power for This Is Africa, a South African news journal. The pay was confusing, it involved an elaborate bank transfer that whittled the funds down to about $50 per article, but stretching my hand across the Atlantic connected me to a broader world at a time when America itself was under siege. News cycle running us dead on an engine of fear. An engine that wouldn’t stop because it was built upon the same principle as America itself: You must kill whatever kept you alive because we are dying. Always forgetting that if we do not, we do not. South Africa had already been there with its own dictator—and the ensuing fight to end the apartheid we still are facing. Blue versus red, the real race battle.

This Is Africa was a journal rooted in intellectual discourse and debates around a future. The future. Qualities I admired not only in the journal but in my editor, Percy Zvomuya, a Zimbabwean. I felt empowered working for them, recognizing that I was part of a global union who had always fought the oppression of those threatened by progress, a global majority. The phrase “This is Africa” was welcome invitation into survival. “This is America” was a phrase I only heard bolstering the bonfire of how backward we’d become.

And “This is American” is something I’m unable to say. I am American, but America loves to forget that. African Americans are still fighting for the right of full citizenship in the US, with our lives hanging in the balance. But I love America, because the Black experience is a very American experience. Music, dance, sports, fashion—our country’s greatest cultural exports came from its African roots. Being a Black American can be real cultural capital when traveling, because the world sees us with more appreciation than our own country does. We are the image of pride worth imitating.

I think of this story my mom and her Ghanaian friend used to tell about their eighties friendship. About the parallels of their teen years in the seventies on opposite continents. According to their conversations, West Africans started wearing Afros because the boldness of its style and its politics were a chic thing to be in line with. The rising promise of Black Power, a new order. But my mom and her friends all sported their Afros for one reason, as a way to reconnect with their African heritage, as a sign of solidarity.

It’s why I like “Black” instead of “African American.” “African American” references what divided us, continents, imagined delineations. “Black” represents what unites us, ideas. Watching hip-hop music videos in the Netherlands, I was surprised that Dutch, French, and South African rappers referred to Malcolm X and Dr. King when discussing freedom. I didn’t feel safe in America, let alone free. What I got as an answer was that there was an international understanding that “This is Black culture” is defined by the stories of African American triumphs. I asked why European and Afrikaans freedom fighters didn’t get shout-outs in the songs I knew.

“America is who we look to,” an Eritrean-Dutch friend told me, “it’s what people know.” I understood what she meant, but I hadn’t thought about it. Black America has worked hard to make sure we’re heard. We are loud enough, audacious enough, to make sure the whole world knows it. But when the world prioritizes our images of freedom above all others, the big “B” in Blackness becomes America’s way of marginalizing everyone else.

Loud isn’t always the solution that’s needed. I still want to know who is accountable for the freedom of Blackness in other languages. The poet Nikki Giovanni once said English is a terrible language because we “speak it, instead of speaking through it.” Blackness can be like this. The need for capital‑B “Blackness” as an ethnic modifier arose from slavery, not skin color. With the creation of an African diaspora came a need to find a unifying element. Since we are not all joined together by religion or skin color, culture became the substitution.

But when we center that culture around American culture, we miss so much. Capital‑B Blackness, despite its global appeal, is not a global unifier. It’s one part of the Pan-African vocabulary, maybe the most popular but not the only one. The difference between [capital‑B] “Blackness” and [lowercase] “blackness” is the difference between a shout and a whisper. Knowing the difference is a crucial travel skill. I like to think of Blackness as a lighthouse on the edge of an ocean. Blackness might lead the way, but it is blackness that fills the shores.

*

In Harare, the sky is pitch, lined with a pink-gold seam of dispensation stirring in the background, the car gliding over the crunch of crisp dead leaves. Farai, our night’s guide, an up‑and-coming contemporary novelist, is opening another beer. Some of the foam sloshes against the dashboard. I’m sitting in the back cross-legged, horrified, holding on to the door handle and my seat belt for dear life. Everyone else in the car is Zimbabwean. I look around in the dark and they’re all quite calm, the bumpy fast-paced ride nothing for them. Farai looks at me. I believe he caught the whites of my eyes widening in the back seat as we hit a large divot and he launches into a monologue meant to soothe the car’s only American.

Capital‑B Blackness, despite its global appeal, is not a global unifier.

“We’re used to this,” he says, “the freedom. The reason why you are having such a hard time adjusting to driving this fast on an empty road on this night is because you still think of yourself as Black. Because you’re still expecting repercussions for your Blackness. Here there are no white police. Worst-case scenario, we get stopped by a cop who knows one friend of ours or another, we pay a fine, we move on.”

Farai’s words were direct, horrifying, and truthful. Blackness in America was rarely something from which I could “move on.” But I didn’t get a chance to respond because we’d arrived at a dance spot that still had the lights on and Afro‑beats rattling the windows. He pulled the parking brake, self- satisfied, and hopped out of the car—my brain still banging against the engine behind him.

He was right. I hadn’t been scared for my life because the car ride was dangerous, I was scared of the car ride and my Blackness. I had never just been me. A Black man driving and dancing in a car full of us in the dark was a death sentence in America. I knew it. I was used to living in the margins, not in a country, and I had succumbed to the likelihood of my death by the most ordinary but unnecessary means.

I don’t agree with fighting for the monolithic use of “Black‑ness” to describe all people of African descent. It’s not enough. We need more language so that we “speak” to each other and not just through each other—through Dr. King, and Malcolm X, and the assumption that Blackness can represent everybody with African ancestry. As long as we do this, we limit ourselves. We say some of us are “in” and some of us are “out.” In this age, we don’t just need the summary version of the diasporic experience, we need every story.

When we treat Black culture as the global ethnicity of the diaspora, we miss that there are black people everywhere who don’t fit neatly inside it. I’m not just talking about expanding the vocabulary of Blackness for the sake of Americans and Caribbeans, I’m talking about thinking of people throughout the globe—Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands, and the Middle East. In traveling to these places, I’ve had to be corrected because I assumed we were not the same, not part of the same origin story, but we are. If we let Blackness create division between “us” and “them,” colonization wins.

__________________________________

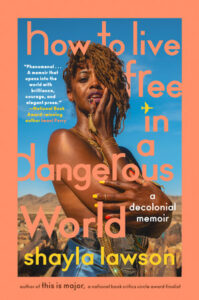

From How to Live Free in a Dangerous World: A Decolonial Memoir by Shayla Lawson. Used with permission from Tiny Reparations Books, an imprint of the Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Shayla Lawson.

Shayla Lawson

Shayla Lawson is the author of This is Major, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics’ Circle and the LAMBDA Literary Award, and two poetry collections. Lawson has written for New York Magazine, Salon, ESPN, and Paper, and earned fellowships from Yaddo and the MacDowell Artist Colony. They reside in Lexington, Kentucky. They’ve “lived” everywhere.