Big Names in Little Magazines: On Thomas Pynchon’s Very First Literary Journal Appearance

Nick Ripatrazone Goes Deep into the Literary Journal Archives

“Thomas Pynchon is a young writer, just twenty, who has previously published fiction in Epoch. He is a Cornell graduate and now lives in Seattle.”

Writers know that the time between when a piece is accepted by a literary magazine and when it is actually published can be rather protracted—my longest span was three years—and by the time Thomas Pynchon appeared in the Spring 1960 issue of The Kenyon Review, he was a still-young 23. He’d just graduated from Cornell, his time there split by a stint in the Navy. He worked for Boeing in Seattle—writing for Bomarc Service News, an internal newsletter.

Although tasked with writing technical pieces about anti-aircraft missiles, Pynchon was characteristically wry. In “The Mad Hatter and the Mercury Wetted Relays,” Pynchon informs readers that Lewis Carroll’s Mad Hatter had gone mad from “chronic mercurialism” or “hatter’s shakes,” which could affect Boeing workers if certain wire-wrapped glass capsules explode. “When dealing with mercury,” Pynchon warns, “even in small amounts, respect it and play it safe. Don’t become a ‘Mad Hatter,’ you might find it to be much more unpleasant than attending a mad tea party.”

The same jaunty rhythms mark “Entropy,” Pynchon’s story in The Kenyon Review. Although he would later dismiss the piece as an example of “overwriting,” something “too conceptual, too cute and remote,” the story is playfully chaotic—the type of glorious excess for which literary magazines are made.

Readers almost stumble into the story’s first line: “Downstairs, Meatball Mulligan’s lease-breaking party was moving into its 40th hour.” Within the story’s first paragraph, the characters indulge in champagne and benzedrine and more, wearing “horn rimmed sunglasses and rapt expressions.” Some people—including Meatball and “government girls” who might work for the State Department and the NSA—slept. The story only gets stranger.

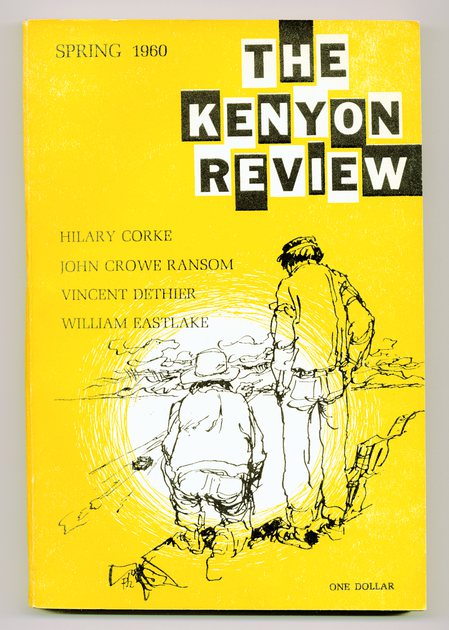

Young Pynchon didn’t even merit mention on the magazine’s cover; an illustration by Paul Hoffmaster of two men standing on a cliff, looking at a road below. Featured on the cover are Hilary Corke, John Crowe Ransom, Vincent Detheir, and William Eastlake, whose plainspoken story “What Nice Hands Held” reveals the issue’s range.

Poetry can pepper an issue of a literary magazine, but fiction offerings are necessarily few. Often the longest pieces in an issue, they must serve as an anchor. Eastlake’s story appears earlier in the issue than Pynchon’s, and is far more cautious and methodical. It is also full of great lines: “Although I distrust people with accurate memories I think the second idea was to drink a lot.” “A man carrying the weight of a saddle is easy to track even if he tries to fool you.” The story ends with a mysterious death: the “tombstone has since dissolved. Everything was made of mud.”

*

One of my favorite teachers, the novelist Tayari Jones, told me that the first page of a story is prime real estate. The page ultimately has a form dictated by someone other than the writer—editor, copyeditor, designer—yet the intended spirit of an opening page must carry its own energy and space.

The high school literary magazine that I advise, Mind Carpenter (what a deliciously 70s name!), publishes 88 pages in each annual issue. We know exactly how much room we have in our house. A magazine is part of an endless tradition, but each individual conversation must end. We need our breaths; we need a break.

The acceptance of a story by a magazine is a commitment. The editors commit pages; readers commit time.

Pynchon and Westlake were among other fiction giants in the pages of The Kenyon Review during the 50s and 60s: Hisaye Yamamoto, Flannery O’Connor, Katherine Porter, and Don DeLillo. As Gordon Hutner has said of the magazine, founding editor John Crowe Ransom’s “purpose was nothing less than to create a journal where literature and literary criticism would be treated with the same seriousness as politics or philosophy, not as an adjunct to such inquiries.” Fiction for fiction’s sake is a lovely idea.

*

Founded in 1941, the Antioch Review began publishing occasional all-fiction issues in the mid-1980s. In the Spring 1987 issue, guest editor Nolan Miller described “a bewildering avalanche” of submissions. When we read short stories, Miller writes, “our attention is more concentrated, the intensity of our perceptions more manipulated. I even think we are more critical, more apprehensive, though at the same time more hopeful, that the writer will succeed in pleasing us with a fully realized experience.”

Although we “remember novels more readily than most short stories,” Miller argues that stories “linger longest in our minds.” The relative brevity of short stories renders them as flashes of life—carrying the same power as unfinished conversations, momentary glances, and old acquaintances.

Longtime Antioch Review editor Robert S. Fogarty has written that short stories “continue to be powerful engines for social description, for social imagination, for self-reflection, for aesthetic possibilities, despite the limitations they impose on both writer and reader.” The Summer 2014 fiction issue of the journal teems with great work from these “literary exiles,” and begins with a quote from Flannery O’Connor: “The main concern of the fiction writer is with mystery as it is incarnated in human life.”

The first story, “Troth,” is a hypnotic narrative by Gordon Lish: a conversation between narrator and reader, replete with questions and confessions and provocations. The narrator admits that he used to spell populace as populus—and is aware that he doesn’t “set them off with quotation marks or with italics” in the story. Why not? “Because I went ahead and figured you for a savvy enough person for you to be able to see what I, Gordon (Gordon!), have been going through for me to get you to understand me without me going to all the trouble of me every two seconds having to take your hand and hold it until you get the essence of what I, Gordon (Gordon!) am trying to say to you.”

The final story, “Migration” by Lusia Zaitseva, is the opposite of Lish’s tone and manner. The result: a narrative and imaginative journey through fiction in a single issue, arriving at a story collectively narrated by whales. They “are muddy-bellied and wry. All things considered, ours is a humane appetite.” It is a wonderfully melancholy tale, addressed to us: “Today you content yourselves to watch us. You have found other means to light your lamps, to make your magazines. But when we die we still float, our bodies find no solace on the sea’s bottom.”

*

One of my favorite collectively narrated works is The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides, his breakout book. A few years later, Eugenides was still publishing in literary magazines, because that is where new writing lives.

Conjunctions, founded and edited by Bradford Morrow, published Eugenides’s “Timeshares” in Issue 28 (1997). The narrator’s father is in the process of refurbishing a rundown motel in Florida. The narrator walks the property, and notices “painting tarps and broken air conditioners lying on the floors. Water-stained carpeting curls back from the edges of the rooms. Some walls have holes in them the size of a fist, evidence of the college kids who used to stay here during spring break.”

His father is converting the motel into a timeshare, and is getting a bit desperate: “A couple of days ago, my father started offering complimentary suntan lotion to anyone who stays the night. He’s advertising this on the marquee out front but, so far, no one has stopped.” “Timeshares” is a quiet, sad tale—rather a song of lamentation on the part of its narrator.

Eugenides vanishes behind the words, in contrast to the two short stories by David Foster Wallace in the issue. Those stories arrive as breathless blocks; the second, “Think,” depicts a man’s affair with “the younger sister of his wife’s college roommate.” The man kneels before her in a room—an involuntary action, “he simply finds he feels carpet and weight against his knees.” Before him, “she stands confused.” He looks like he’s about to pray.

It is a tantalizingly uneven story—almost unfinished. Yet in its rawness, “Think” captures a man contemplating bad things with a woman, while “her sister and her husband and kids and the man’s wife and tiny son have taken the man’s Voyager minivan to the mall.” He’s a mess. She’s wondering what she got herself into.

And Wallace ends the story perfectly: “And what if she joined him on the floor, just like this, clasped in supplication: just this way.”