Beyond Saviors and Suffering: On the Complex Dynamics of Animal Rescue

Carol Mithers Explores the Relationships Between Stray Dogs and the Humans Who Love Them

January 2023

Southeast Los Angeles

The puppy had gotten into the meth. She held herself very still, eyes slits, a sliver of pink tongue protruding. Now and then, she squeaked. It was hard to tell if she was stoned or dying.

Distraught, Reena reached through the open trailer window and dropped her into Lori Weise’s arms. Two months before, her young Doberman mix, Luna, had given birth to six puppies, and now half were dead. The last had died in the jaws of her other dog, Kiki, a low-slung gray pit bull. It was probably because Kiki had thought the puppy was a rat—there were a lot of rats inside Reena’s trailer, so it was an honest mistake. Still, Reena didn’t want another death on her conscience. Lori, the head of Downtown Dog Rescue, had been coming to this neighborhood for a year. Reena had faith in her. She could take the puppy to the vet.

“You’ll bring her back, right?”

“We’ll see,” Lori said evenly, the small body warm against her. She was always careful not to make promises she might not be able to keep.

The story of the Dog Lady isn’t the kind of standard pet tale that one usually encounters.

In early 2023, encampments of unhoused people stretched all through Los Angeles, but these blocks south of downtown and north of Watts, where county and city borders met, were like the far edge of nowhere. At least a hundred men and women lived with uncounted numbers of dogs and cats in rusted-out, tarp-covered RVs, vans, and cars. Below walls topped with razor wire to protect local businesses, sidewalks lay buried in trash. There were no trees, water, power, bathrooms, services of any kind.

Even here, Reena’s place stood out. She spent her days scavenging with a shopping cart, Luna at her side, and kept everything she found. County crews had been out that morning to clear the worst of the mountain of garbage that had grown around her trailer, one so high and wide it blocked the street. But mounds of junk still cluttered the trailer’s roof and stewed in rain puddles at its doorless entrance: bicycle parts, paper, wrappers, rags, a pile of feces, a decomposing rat. A ragged length of green-and-red Christmas tinsel hung from the antenna, and two dozen wrapped heads of cauliflower, pulled from some supermarket dumpster, slowly rotted on an outside shelf. A fecal stench rose from the street and trailer window.

“Is the puppy gonna die?” Reena asked. It was hard to say how old she was—forties?—or of what ethnicity. Most of the people on these blocks were Latino, local kids who’d grown up in the area and never left. Reena could speak Spanish but had an Anglo’s pale skin and blue eyes. Her hair stood on end, tips dyed purple. Her teeth were broken, her hands blackened with dirt. She wore a long black cape, its hood pulled over her head, like a figure from a scary fairy tale.

“I hope not,” Lori said. “We’ll get her checked out right away.”

Reena nodded. Like virtually everyone around her, she was a drug user. Thankfully, today she seemed sober—when she was on a meth high she whispered and walked in circles—and was alone. There was a boyfriend in the picture, who held title to the trailer and used the ownership as a weapon. Once, when Lori knocked, Reena emerged to announce, “We were fucking!” and her face and feet were cut, as if she’d been beaten.

“What about the two other puppies?” Lori asked. “I’m worried about them. I can have the vet check them out.”

That appeal might work. Reena was a mess, but Lori thought she had a good heart. Over time, she’d learned there were two kinds of street dwellers with pets: those who valued them only for protection or bred them for money, and true animal lovers. Reena seemed the latter. Both her dogs had been strays, wandering hungry until she took them in.

“No.” Reena pointed at Luna, who nuzzled Lori in search of a pat. “Losing all her babies will freak her out.”

“Okay,” Lori agreed. “Not today.” It broke her heart to leave the puppies behind, but this wasn’t the time to push. Her work in the area was a planned, strategic operation that could have an outsized impact on LA’s pet overpopulation. None of the free-roaming animals on these blocks had ever been taken to a vet, vaccinated, or fixed, and they sickened, suffered, and reproduced accordingly—look-alike sibling and half-sibling offspring were everywhere. In one week alone, ten puppies had been found in trash heaps. The residents had come to accept Lori’s offers of pet food, medicine, and spay/neuter surgery because they’d learned to trust her. Nearly thirty years working in the grittiest reaches of LA had taught her that to get there, you had to go slow. You couldn’t lecture or snatch animals and run.

It was time for her to get out. Lori was very aware that two young men fiddling with a nearby RV kept looking her way. Maybe not surprisingly—a very slender, almost-six-foot-tall, whiter-than-white fifty-something woman with red hair was obviously, blazingly, an outsider. Even dressed in plain cargo pants and a fleece, she had a rough elegance. Her posture was perfect; she moved like a dancer. To be noticed was a danger. Powerful gangs ran the local drug trade, along with the underground gambling operations called tap-taps. Owe them, cross them, and you could end up dead. The blackened hulks of firebombed trailers sat on several blocks as a warning. The victim of the most recent attack was in the hospital with third-degree burns.

“Take care of yourself, Reena. We’re off to the vet.”

“Keep her awake.”

“I will. I’ll be back.”

That promise she could keep. The woman they called “Dog Lady” always came back. And she’d felt drawn to these streets ever since she first saw them. They reminded her of the time and place where she found her life’s work: downtown LA in the late 1990s, its sidewalks and alleys full of homeless dogs and people. Another world of need that no one else seemed to see.

*

The story of the Dog Lady isn’t the kind of standard pet tale that one usually encounters, one in which a photogenic dog or cat suffers, then is saved by a heroic human. That story has become so ubiquitous that we don’t even consider its origins, much less notice what it leaves out or its effect on us.

Lori’s journey began at a pivotal moment for domestic animals. Two overlapping and complementary movements were striving to upend more than one hundred years of accepted policy and vastly improve conditions for pets. “No kill” aimed to end the routine slaughter of unwanted dogs and cats in the nation’s animal shelters; “rescue” was a volunteer effort to find those same animals homes. To an extraordinary degree, both succeeded, in practice and in the wider culture. As the routine killing of homeless animals was redefined as a moral outrage, shelter policies changed. Adopting a shelter pet became a badge of honor. Although the killing never stopped entirely, the number of animals who died plunged.

The history of animal sheltering, euthanasia, and the effort to stop it was a simple story…. I believed that myself, until I got to know Lori.

Less benevolently, as these movements created a subculture that absorbed vast amounts of time, money, and political will, they also popularized a central narrative: Animals were imprisoned to suffer and sometimes die in shelters because bad humans failed them. Good and righteous humans saved them, undoing the evil that others had caused. Explicitly, implicitly, this narrative permeated the no kill/rescue world, then beyond. It was there in a YouTube video showing a gentle-eyed young woman offering food to a fearful hungry dog, in the paraded images of misery that made up humane organizations’ fundraising appeals, in a journalist’s account of a man taking neglected dogs from overcrowded Southern shelters to adopters in the Northeast, where he “scoops them up in his powerful arms, and places each one in the bosom of their new loving family.”

Stirring but also deeply judgmental, it was embraced by the movement’s mostly white and affluent supporters, who saw themselves on the “righteous” side of the equation. As Nathan Winograd, one of the no kill movement’s more strident advocates, put it, the history of animal sheltering, euthanasia, and the effort to stop it was a simple story “of heroes and villains, betrayal and redemption.” I believed that myself, until I got to know Lori.

I met her in 2012. By then, the no kill/rescue movements’ imperatives were mainstream. Across the country, men and women proudly introduced their four-legged Buddys and Jacks as “my rescue.” I’d heard enough slogans like “Adopt, Don’t Shop” that when my family decided to get a dog in 1999, we didn’t for a second consider going to a breeder. I knew almost nothing about rescue mechanics, though. A classified ad for “pet adoptions” led us to Haskell, a middle-aged yellow Lab, who’d been found as a stray and was being offered by a rescue group.

It was the first such group I’d ever dealt with, and I was floored to be given a long application questionnaire and to discover someone would be coming to check our yard for fence height and shade. (Five years later, after Haskell passed away, we went back to the group and adopted Casey, a Chow-mix puppy; this time, as “repeat adopters,” we were excused from inspection.) Then I got interested in a story set in the rescue world. To learn more about it, I reached out to an old friend who ran her own rescue. She also suggested I contact Lori.

We got together in downtown LA and talked outside the upscale furniture factory that she managed. For more than fifteen years the factory had been Downtown Dog Rescue’s home base, and its parking lot held a kennel with several dozen street and shelter dogs that were on their way to new homes. The interview was helpful and eventually I wrote the piece. But that day I also listened, open-mouthed, to some of Lori’s stories about her years downtown and her ongoing work with low-income and homeless pet owners in South LA and Compton. I wanted to write about her, although what I imagined lay firmly within the conventional narrative, all savior and suffering. That piece never got written. The next eleven years, during which I talked to Lori at first intermittently, then constantly, taught me how complex a “simple” story could be.

__________________________________

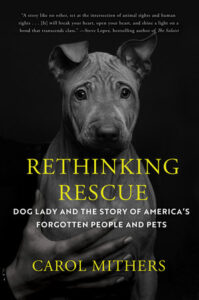

Excerpted from Rethinking Rescue: Dog Lady and the Story of America’s Forgotten People and Pets by Carol Mithers. Published with permission of Counterpoint Press. Copyright © 2024 by Carol Mithers.

Carol Mithers

Carol Mithers is a journalist who has written about Los Angeles, women’s issues, and extraordinary women for over thirty years. Her work has appeared in The New York Times; Los Angeles Times; LA Weekly; O, the Oprah Magazine; Los Angeles Magazine; More; Town & Country; Architectural Digest; Ladies’ Home Journal; Parenting; The Bark; The Nation; California magazine; Buzz; Salon; The Daily Beast; and elsewhere. She is also the author of three books, including Mighty Be Our Powers: How Sisterhood, Prayer, and Sex Changed a Nation at War, written with Nobel Peace Prize laureate Leymah Gbowee. Mighty was a finalist for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize and has been reprinted in fourteen languages. Mithers lives in Los Angeles, where she has raised three demanding rescue dogs.