Beyond Institutions: Why Black Empowerment Must Bridge the Opportunity Gap

Andre M. Perry on the Ongoing Struggle For Racial, Social and Economic Justice in America

The quest to secure Black power is not and should not be understood as a mission to emulate white power or simply to gain access to white institutions. In their attempts to spotlight inequality, people often cite comparisons to white society in ways that tacitly reinforce white norms and standards. An example of this is when Jay-Z called out the Grammys for failing to honor Beyoncé with its highest prize, the Album of the Year award. Doing so helped reinforce the notion that white culture, white identity, and white-centric institutions are the standards or norms that others are expected to follow.

White normativity is fundamentally about power and its invisibility, underscoring the privilege of whiteness to establish such standards. Anthropologist Gloria Wekker argues that white norming creates a “racial grammar” that shapes thoughts, effects, and even individual self-perceptions, in a profound cultural archive that inherently favors whiteness. This dynamic enables white individuals to assume positions of invisibility and superiority, perpetuating a standard by which whiteness is the benchmark of humanity such that deviation from this norm is seen in racialized terms.

While the Recording Academy is not a “white institution” per se, its development has been white-centric, and it has a long way to go before becoming a truly multicultural organization in which racial bias doesn’t have a negative impact on its subjective valuations. More important, winning more Grammys isn’t going to move the needle on increasing Black wealth.

In the context of seeking recognition and representation within predominantly white institutions, assimilation is not inherently a goal or an indicator of Black power.

Still, influencing cultural institutions is nonetheless important to power building because institutions shape narratives about the human condition. All sponsors of art explicitly or implicitly color our notions of what constitutes high and low culture, how it looks, sounds, and smells, and these notions shape public policy. The harmful effects of demonizing Blackness were powerfully demonstrated in the famous doll test, in which Black children, presented with similar Black and white dolls, identified the Black dolls as “ugly and bad.” By exposing that harm, the test helped plaintiffs win the landmark 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which overruled the “separate but equal” doctrine that had legally enshrined segregation. Through such efforts and through art and culture, in books like Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, society has come to see the inherent value bestowed on whiteness and the burdens assigned to Blackness that undergird social policy.

In the context of seeking recognition and representation within predominantly white institutions, assimilation is not inherently a goal or an indicator of Black power, given the problematic dynamics involved. While the historical struggle for equality has aimed to eliminate the bias and discrimination that hinder assimilation, the process of assimilation often involves compromising dignity and stripping away important, often immutable, aspects of one’s identity—that is, whitewashing. The ubiquitous practice in professional life, especially in entertainment, requiring people to straighten their hair to mimic white styles is a glaring example. (Thankfully, CROWN Act legislation, which prohibits hair discrimination, is being passed across the country.)

However, whitewashing does reveal the intrinsic and material advantages of whiteness. Black homeowners, for example, can increase the worth of their property—adding thousands in actual value—by replacing Black art, books, clothing, and hair products with items that signal white ownership. In 2020, the New York Times reported on a Jacksonville, Florida, couple whose home yielded a 40 percent higher appraisal value after they whitewashed it. That same year, an Indianapolis woman did the same and enlisted a white stand-in, boosting the appraisal by $134,000. One Black homeowner, who gained some $300,000 in value after whitewashing her home, told me that she feared the appraiser was on to her when she left a jar of cocoa butter on the dresser.

There are those who see emulation as the path to Black power, expressed as needing to “do what the opposition does” and out of a desire to adopt the same playbook used to discriminate against Black people. This eye-for-an-eye strategy runs the risk not only of dehumanizing those who use it, but also of replicating the outcomes with which Black people currently live.

My research makes it clear, for example, that being better capitalists will not significantly advance the Black community’s socioeconomic status. There is a complex relationship between Black power and economic empowerment, but individual wealth, exemplified by Black billionaires, does not inherently translate to collective advantage. It may even reinforce racial and economic hierarchies.

Acclaim from mainstream institutions, assimilation, whitewashing, and emulation will not provide the flex that gives Black people the capital and influence they need. Nor will achieving parity in prestigious awards. This will not restore the home value that’s been denied by racism or increase homeownership, which point to a truer assessment of Black power. The metrics by which we should measure Black power and the goals we must set to achieve it involve advocating away from individual achievements and toward collective progress and well-being.

The expansion of Black power and the metrics we use to assess it requires setting self-defined material and communal standards, free from the markers of success prescribed by others.

In the new renaissance, the Black Americans who write the stories, sing the songs, cook the food, and dribble the basketballs are demanding sovereignty and ownership: they seek their own platforms to show their full humanity and establish new lines of authority. They seek to build institutions that hire employees who are paid a living wage. They are engaged in activities that build up communities rather than exploit them. Thus rapper Killer Mike, Ambassador Andrew Young Jr., and media executive Ryan Glover cofounded Greenwood, a mobile banking platform inspired by Black Wall Street, which flourished in the early 1900s Greenwood district in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Cultural leaders are building venues, organizations, and bodies of work that heighten their control and commercial value.

The names Ibram X. Kendi cites in a widely read 2021 Time essay aren’t just a Black History Month roster (the month of recognition has itself become a racist trope) or a rattled-off list of successful people. While he acknowledges the brilliance of the work of producer-actor Issa Rae, director Regina King, performer Billy Porter, writer Jason Reynolds, and others, his point is that the power of their artistry comes from a newfound capacity to set self-defined cultural standards, ones that are driven by the ways in which Black creatives experience humanity and are free from the burden of fulfilling white norms. In the same way, the expansion of Black power and the metrics we use to assess it requires setting self-defined material and communal standards, free from the markers of success prescribed by others.

*

In the landmark 2023 ruling Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, the US Supreme Court struck down race-based affirmative action in college admissions. The Supreme Court ruled that Harvard College and the University of North Carolina had violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by employing admissions processes that intentionally discriminated against Asian American applicants based on their race and ethnicity. As a result, the court mandated that universities cease using race as a factor in future undergraduate admissions decisions. The ruling also requires that the process be conducted in a manner that prevents those involved in making decisions from knowing the race or ethnicity of any applicant.

The Supreme Court’s decision has opened the door to questions of whether similar legal arguments can be made under related laws, specifically Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which addresses employment discrimination, and Section 1981, derived from the post-Civil War 1866 Civil Rights Act, which ensures that certain rights previously exclusive to white individuals, including the rights to make contracts and own property, apply to all US citizens. Scholars at the Stanford Center for Racial Justice believe that the court might well apply the same reasoning to these statutes as it did in the Students for Fair Admissions case. This precedent has encouraged those who have challenged affirmative action policies to also target newer diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs and initiatives.

DEI, affirmative action, and environmental, social, and governance programs represent institutional responses to the mobilization and organization efforts of Black communities. But these tactics and tools are not the ultimate goals. The concepts, strategies, and objectives of Black power have never been fully encapsulated by such programs. The true endpoint has always been securing the means to ensure long lives and well-being. Tactics will change, but Black power must be gained alongside racial justice to increase longevity and provide restitution.

__________________________________

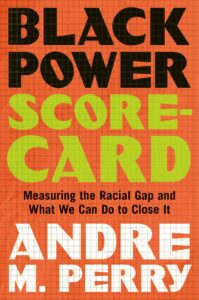

Excerpted from Black Power Scorecard: Measuring the Racial Gap and What We Can Do to Close It by Andre M. Perry. Published by Metropolitan Books, an imprint of Henry Holt and Company, a division of Macmillan, Inc. Copyright © 2025 by Andre M. Perry. All rights reserved.

Andre M. Perry

Andre M. Perry is the author of Know Your Price: Valuing Black Lives and Property in America’s Black Cities. He is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and the director of its Center for Community Uplift as well as a professor of practice of economics at Washington University in St. Louis. He lives in Prince George’s County, Maryland.