Between Languages: Yukiko Tominaga on Writing in English and Japanese

“Switching around the two languages frees me from my own stigma.”

Japanese and English have nothing in common. Even though I’ve lived more than a half of my life in the U.S., I’m still afraid of English. I second guess articles, comma placements, phrasal verbs, prepositions, and tense matching; I worry about my limited vocabulary, and most importantly, I wonder if I am expressing myself in a way other people understand.

I thought if I was able to write a story in English, maybe the rest of the things that comes to my life wouldn’t look so hard including raising a child by myself. If I can face my fear, maybe I can survive in the U.S.

It has been almost 16 years since I started writing stories, alternating between Japanese and English. English still scares me, but the language brought me the courage to raise my child in this country, connected me to wonderful people, and gave me the confidence that, with my imagination accompanying me, I could survive not just in the U.S but under any circumstances.

*

When I write in Japanese, I see America more objectively. I am not swayed by opinions around me and often I rediscover why I love this country even though life in the US feels like it’s all about survival. When I write in English, I find Japan and Japanese people to be fascinating. I stop trying to make sense of them and rather let them be and appreciate their complexity as they are. Switching around the two languages frees me from my own stigma. As much as I desire to belong one place, it is a privilege to be a stranger in both my countries.

When I am stuck in either language, I start to translate the Japanese portion to English or vice versa. By the time I’m through it, I am ready to go back to writing another scene. I do this not for craft reasons but rather to keep my hands moving. The key is to contain myself in the world I am creating. Get the shape of the story.

Rhythm is what I care about the most in my stories. The rhythm of haiku and tanka sit with me very well. I don’t follow the rules of haiku or tanka but in my mind the same beat runs through my body, and I hear it when I read my Japanese draft aloud. In the English version, I can never recreate the same rhythms, instead, I am after my own beat. The beat in line level becomes a paragraph level which becomes a chapter, then a novel.

When the story is working for me, I feel great love for all humanity.

At Counterpoint Press, where I work as an editorial assistant, I edit translations of Japanese books, introducing never-before-translated authors for English readers. I am constantly forced to think about two languages, asking myself, “What do we want to deliver to the reader the most?” I learn from our translators that it’s a delicate dance of addition, subtraction, rearranging lines to recreate the soul of the author’s work.

For my own work, I have all the liberty in the world. I can prioritize the rhythm of the piece over the content. I wrote the first half one of the chapters in my book, “Never Ever War”, fully in Japanese. In the chapter, some of the protagonist Kyoko’s thoughts appear from nowhere and it feels like I am picking a slide photo randomly. But I feel the beat in my body, so I know it’s the correct order. For the English version, I rearranged the scenes in a more chronological order because when I read the story aloud, the beat didn’t sit with me. I flipped two paragraphs and did some additions and subtractions.

In Japanese, timelines can be looser than in English. For example, I can write, “I eat dinner, go for a walk, and finished my night.” We are not so strict about tense; we understand it from the context which give some freedom to readers to make up their version of the story. This is because when we talk about the past we are living in the past therefore, the past is the present. Let’s say I am talking about my child’s birth and start to cry. The past is happening in me as I speak. I am crying because the emotion is present. How can you say it is past? I use the chapter and entire book to show that time is only a concept that humans created.

In some stories, I combine a few sketches into one and add connective tissue to complete a story. That same principle applied for building my first novel. I put together stories in the order to mimic the process of grief without thinking about creating a novel. My novel was not deliberate, but eventual.

What is my writing process? Ask me the same question tomorrow, I will answer differently because explaining process is reflection, the after thoughts. Just like memories, the past is a narrative that I create based on my present moment. One thing that remains always true is when to end my story.

For me, it’s when I feel kindness.

If I still hold some meanness towards the character, I know I have more work to do in my story. As I spend so many hours with my characters, I learn to embrace their strengths and defects. The love for my character expands beyond my fiction. When the story is working for me, I feel great love for all humanity. This is how I know that the story is done.

__________________________________

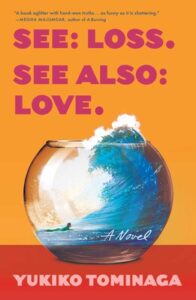

See: Loss. See Also: Love. by Yukiko Tominaga is available from Scribner, an imprint of Simon and Schuster.

Yukiko Tominaga

Yukiko Tominaga was born and raised in Japan. She was a finalist for the 2020 Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction, selected by Roxane Gay. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and has appeared in The Chicago Quarterly Review, The Bellingham Review, among other publications. She also works at Counterpoint Press where she helps to introduce never-before-translated books from Japan to English language readers. See: Loss. See Also: Love. is her first book.