Between Fear and Resignation: How German Writers Reacted to Hitler’s Rise

Uwe Wittstock on Intellectual Suppression in the Early Days of Nazi Terror

These are no tales of heroes. They are stories of people facing extreme peril. Many of them refused to acknowledge the danger, underestimated it, reacted too slowly, in short: they made mistakes. Of course, it is easy for anyone paging through history books today to say such people were fools if they could not comprehend in 1933 what Hitler meant for them.

And yet such a notion would be unhistorical. If the claim that Hitler’s crimes are unimaginable has any meaning, then it must hold true first and foremost for his contemporaries. They could not imagine or at best could only suspect what he and his people were capable of. Presumably it is in the very nature of a breach of civilization to be difficult to imagine.

Everything happened in a frenzy. Four weeks and two days elapsed between Hitler’s accession to power and the Emergency Decree for the Protection of People and State, which abrogated all fundamental civil rights. It took only this one month to transform a state under the rule of law into a violent dictatorship without scruples. Killing on a grand scale did not begin until later.

But in February ’33 it was decided who would be its target: who would fear for her life and be forced to flee and who would step forward to launch his career in the slipstream of the perpetrators. Never before have so many writers and artists fled their homeland in such a short time.

*

At around midday, Walter Mehring visits the editorial office of the Weltbühne on Kantstrasse. He’s been writing short features for the newspaper for years, but this time he’s not coming as a contributor, but as the bearer of bad news for Carl von Ossietzky. A friend working in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs paid Mehring’s mother a Sunday visit yesterday and, unsolicited, gave her urgent travel advice for her son: “Your son feels most at home in Paris. He should go back to Paris.” His mother understood right away and asked how long the trip should last. The visitor hesitated briefly. “I would say fifteen years.” The thoughtful man isn’t solely concerned about Mehring, however, but about other authors as well. In the days to come, he predicts, there will be a lot of arrests.

If the claim that Hitler’s crimes are unimaginable has any meaning, then it must hold true first and foremost for his contemporaries.

Ossietzky smiles, listening intently and silently. The information does not surprise him. Mehring implores him to leave the country immediately. Ossietzky demurs, neither agreeing nor disagreeing, but does not object when someone from the editorial team books him a ticket by telephone to the next available foreign country.

At that moment Hellmut von Gerlach enters the room, sixty-seven years old, chairman of the Liga für Menschenrechte, and for decades one of the major central figures of Germany’s left-wing liberal peace movement. Ossietzky admires him a great deal and entrusted him with the editorship of the Weltbühne while he was incarcerated last year.

“Mehring thinks,” Ossietzky tells him, “we all need to get out now.” Gerlach flares up while fiddling with his umbrella: “Enough with the panicking already! Anyway, I for my part am staying regardless.”

“Then I’ll stay, too…!” Ossietzky replies.

As Mehring turns to go, Gerlach wishes him well: “Godspeed.”

Brecht’s hernia operation went off without a hitch, and he came through everything without any complications. For the time being, however, he is still in Dr. Mayer’s private clinic where he is well provided-for. It’s unlikely he could find a more pleasant place in Berlin at the moment.

What comes next is still uncertain. Brecht has of course discussed emigration with other authors now and again, especially the idea of sticking together as a group in exile. But this plan has a critical disadvantage; he and Helene still do not have a passport for their young daughter Barbara, now more than two years old, so they could not legally leave the country with her.

For this reason, they’ve often debated whether it might suffice to hide out somewhere in the countryside for a few weeks until Hitler is forced to resign, maybe in Bavaria. Heinrich Held, the head of the Bavarian People’s Party, seems to hold the reins firmly in hand there as Minister-President and to be keeping the Nazis in check to some degree.

Then, however, as requested, Brecht’s invitation to a reading in Vienna arrived, where his play The Mother is to be premiered, a production he would like to see. For now, he will travel to Austria. But when? And how long will he stay there? One thing is certain. He has to get out of Berlin. He’s had the boxes with his manuscripts and other materials hauled out of his apartment and safeguarded with friends. The children are a difficult matter. Brecht has asked his father in Augsburg to shelter Barbara at his home, for the time being, but how can he ever get her across the border?

Three days ago, Katia and Thomas Mann traveled onward from Paris, the final station of his Wagner tour, to Arosa in Switzerland. It is one of their most favorite places to vacation. Katia Mann was here for treatment twice before because doctors diagnosed an apical catarrh that they feared could portend tuberculosis. Thomas and Katia are so fond of the landscape and the Neues Waldhotel that they enjoy traveling back here even without medical need. This time it is Thomas Mann who would like to relax for a few days after the strains of his work on the essay about Wagner. Afterward he wants to return to Munich, back to his desk, where the manuscript for Joseph in Egypt awaits him. That is the plan.

The seven-story, castle-like hotel offers an imposing vista of the Grison Alps. The view may not be quite as spectacular as the one from the Deutsches Haus in Ticino where Margarete Steffin is currently trying to cure her tuberculosis, but it is impressive nonetheless.

During a stay here in 1912, Thomas Mann developed his initial ideas for The Magic Mountain, and later employed quite a few details of the locale and the hotel in his novel. What enamored him above all was the elongated dining hall, with the full splendor of the mountain panorama unfolding outside its windows. It is furnished in the style of New Objectivity with vivid hues, its walls clad to half height in wooden paneling, above which are wallpaper with colorful stripes and the solid-brass chandelier hanging from the ceiling.

Mann has had his mail forwarded here from Munich, and with it the quarrels involving the writers’ division of the Academy in Berlin have caught up with him. Alfred Döblin described to him the pair of most recent meetings in a lengthy letter: the first in which his brother Heinrich was pressured to resign, and the one in which Döblin attempted to push through a statement of protest, but to no avail. The letter’s summary has an air of resignation; Döblin expects the section will soon be disbanded, possibly just after the elections.

Perhaps it would be better to preempt such a move and resign of their own accord, most preferably as a group. Yet Leonhard Frank, Döblin writes, does not wish to leave the battlefield voluntarily, but to continue fighting. What about the Academy are they defending, though? In any case Döblin feels awful because in public it now looks like they had all accepted Heinrich Mann’s mandated resignation virtually in silence and without resistance.

They could not imagine or at best could only suspect what he and his people were capable of.

René Schickele, born in the Alsace and having labored for decades in essays and novels toward a reconciliation between France and Germany, has also been in touch. Shouldn’t they establish a private writers’ academy, he proposes in his letter, in case the Nazis disband their division?

Yesterday Thomas Mann first sent an extensive reply to Döblin, resorting in it to pugnacious vocabulary. By no means must they do the new potentates the favor, he says, of dissolving their division by themselves. Naturally he wanted to quit as well when he heard of his brother’s resignation, but now he thinks it better to wait for the time being and leave it to the new occupation authorities—as he refers to the Nazis—to abolish the section by force. That, he believes, would be a far more visible event for which the National Socialists would then have to bear responsibility in public. Furthermore, it is impossible to predict, he points out, how things will turn out with Germany. He cannot deny faint hope for the elections next Sunday.

Today he writes to Schickele in roughly the same tenor. In his view the best strategy at the moment is to do nothing. If the Nazis break up the Academy, they once again reveal their intolerance and caprice for all to see. If, however, they leave the liberal authors in their writers’ division, they admit publicly that there is a small group of honest men offering them resistance. For them, both options would necessarily be politically irksome indeed, wouldn’t they?

_______________________________

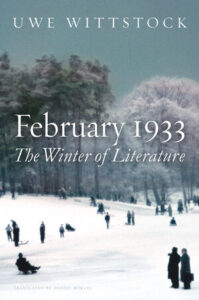

Excerpted from February 1933: The Winter of Literature by Uwe Wittstock, translated by Daniel Bowles. Copyright © 2023. Available from Polity Books.

Uwe Wittstock

Uwe Wittstock is a journalist, critic and author who lives in Germany. A former Critic in Residence at Washington University in St. Louis and a literary editor for the news magazine Focus, he was awarded the prestigious Theodor Wolff prize for journalism in 1989